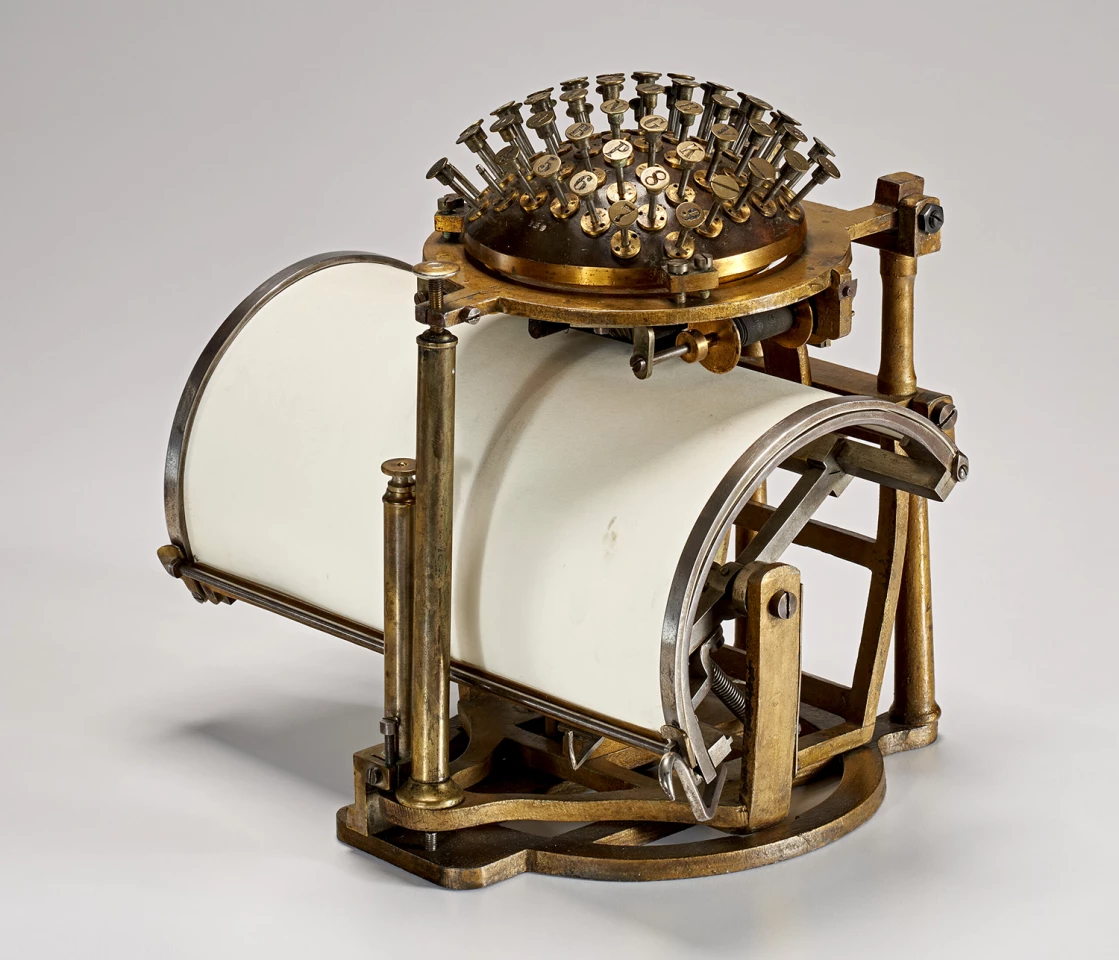

The world’s first typewriter goes to auction in Köln (Germany) on 22 March 2025. Just 35 Malling Hansen Writing Balls remain, 30 are in museums and the battle for one of the few remaining specimens will be worth watching because as the supply diminishes the price goes up.

Though the Sholes & Gliddon (Remington No.1) became the Model T of the typewriter age, there was one notable example of prior art which began manufacture on a very humble, "hand made" scale in Germany.

While a Sholes & Gliddon is these days regarded as the cornerstone of any typewriter enthusiast's collection, the original and quite magnificent Malling Hansen Writing Ball is now all but unattainable.

For starters, only 35 are known to have survived, and the esteem with which the model is held is best illustrated by 30 of the 35 already being in museums.

That leaves five that have escaped capture by the ever vigilant museums of the world. Museums usually don't have any money, but they have staff blessed with historical perspective, and they often get ahead of the game, before the collector money arrives.

In this case, museums have been well ahead of the game, but it's unlikely that the remaining five will end up in museums now, because collectors these days are better informed and have a lot more discretionary pocket money than a publicly-funded museum could ever hope for in attempting to document society's path to here.

Nearly all of the Writing Balls to have reached public auction have come from Auction Team Breker, a "technical antiques" auction house in Köln (Germany) that just held its 100th science & technology history sale. Congratulations to them - historical sci-tech artifacts are just becoming appreciated by the mainstream at auction and Breker has been flying the flag for our technological heritage for much longer than it has paid.

This Malling-Hansen exclusivity is partly because Auction Team Breker has been the center of the European auction trade for historical artifacts from science, technology, office automation and mechanical music forever, but mainly because Ewe Breker, who started it all, is the head of the Malling Hansen Society, giving fellow enthusiasts confidence the machine's next custodian will be a kindred spirit.

Across the last 23 years of New Atlas, we've regularly reported on Auktion Team Breker offering the cream of the tech history crop at auction, selling items such as multiple Apple-1 specimens, more Enigma machines than anyone else, automata, astrolabes, and it's the only place where you'll regularly find one of Thomas de Colmar's original Arithmometers. Some of the items Breker brings to market just have to be seen to be believed – such as this entirely mechanical jukebox.

A brief study of the machine and its contemporaries suggests that the Writing Ball had all the hallmarks of success – it was designed with the user interface foremost in mind, as the original intent was to create a machine with which people not blessed with speech, and/or hearing and/or sight, could communicate quickly with those who didn't understand sign language.

Reverend Rasmus Malling-Hansen was the Director of the Institute for the deaf and mute in Copenhagen, and when he realized that his students were able to phonetically spell with their fingers faster than they could write by hand, he began work on a machine that would enable his flock to “speak with their fingers.”

The “writing ball” was his answer, and considering there was no prior work upon which to build, it is a monument to ingenuity and dogged perseverance. As Sir Isaac Newton humbly acknowledged, his work was built on the shoulders of giants. Malling-Hansen did it all while doing his day job, and he conceived this machine from scratch - there was nothing like it upon which to base the design.

The depth to which the good reverend went in making certain design decisions is remarkable - he thought about separating vowels for conceptual memory, and putting the most common letter pairings together and making it easy to use in so many ways, even to the point of the tactile metal keys for those without sight. The hands-on-sphere interface is designed so you don't move your hands but to press the keys.

In many ways, this machine is being judged as a typewriter when it is indeed much more. It appears to have been conceived more as a translator for the vision-, voice- and/or sight-impaired to be able to communicate faster and he achieved his goal commendably.

It was also received to great fanfare, being the star of two world fairs: the 1873 World’s Fair in Vienna, and the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris. In 1881, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche purchased a Malling-Hansen Writing Ball, becoming the product's most famous user. The International Rasmus Malling-Hansen Society offers the most complete repository of information on this gorgeous technological landmark.

By comparison, the ultimately successful Sholes & Gliddon had some glaring faults: it typed only capital letters (upper case) and you couldn't see what you were writing. Even today, enthusiasts refer to all typewriters prior to the 1891 Williams Typewriter as "blind writers."

The Writing Ball's hand-built production ultimately made it far too expensive for the common man, and the Sholes and Glidden Typewriter was more affordable and became the first commercially successful typewriter.

If you have trouble visualizing how a company functioned prior to computers, networks and mobile phones, puzzle for a moment how companies functioned prior to the typewriter.

Just 150 years ago, if you wished to record something, there was no alternative to writing it down with a pen and ink.

Older readers of this article may have learned to write in such a way (guilty yer honor) – dipping the nib of a pen into an inkwell, and scratching out the words, hoping to have sufficient ink to complete a word, without picking up too much ink and smudging your masterpiece. Writing involved the continual use of blotting paper to remove excess ink. Just 150 years ago, we were still emerging from information's dark ages.

Sixty years later, László Bíró's ballpoint pen hit the market (1931).

It is hence not surprising that the typewriter was one of history's "killer apps."

Think of the typewriter industry as a prequel to the computer industry set one century prior. It informed the evolution of the computer industry and was an important milestone on the road to the technological life we lead today.

Once the typewriter hit the market, it was universally adopted, fueling relentless unprecedented demand from a target audience with the money to pay for it – business – catalyzing a wave of start-ups, competition, innovation and rapid technological progress.

The first mass-produced typewriters began to roll out in the mid-1870s. The Model T of the typewriter age was the Sholes & Glidden, which entered the market on 1 July 1874. A swift uptake saw them become commonplace by the mid-1880s. Every company in the world embraced the potential of the typewriter for correspondence and record keeping. The freer flow of information that the typewriter facilitated drove massive societal and commercial change.

The market became so large that it entrained humanity and the QWERTY keyboard layout it gave us now stands as the most ubiquitous machine-user interface of all time.

The QWERTY keyboard was devised in 1866 for the forthcoming Sholes & Glidden "Type-Writer" and first mass-produced in 1874 when Eliphalet Remington diversified from his core armaments and ammunition manufacturing business and purchased the rights.

The QWERTY layout became the global de facto standard for Latin-script computer keyboards even though it was created to separate common letter pairings so that the typebars would not be coming in at near-parallel angles on consecutive keystrokes as often, and hence less likely to jam if the user typed too fast. The influence of the Scholes & Glidden is evident to this day, and many of the readers of this article have a relic from technological antiquity right in front of them.

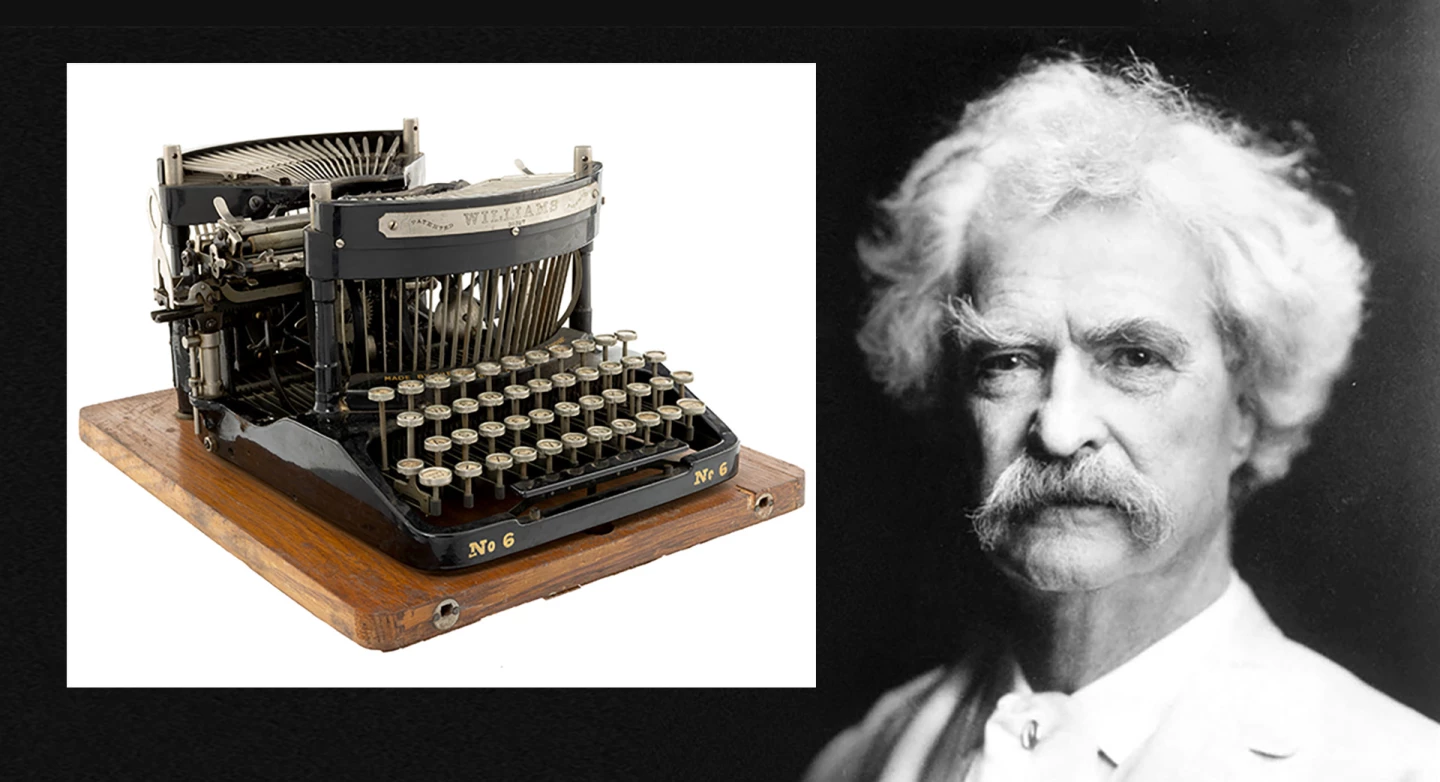

Williams typewriters solved the problem of not being able to see what the user had already written, presenting this previously unavailable and critical information between opposing fans of carriage bars which struck the paper via a "grasshopper mechanism" which Williams had perfected. It was an elegant solution to an engineering problem and it completely transformed the user experience.

In the beginning though, the Malling Hansen Writing Ball was the only game in town for a short time, and like most typewriters of note, it too had a famous user – German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

That was another factor we noticed when looking back through auction history. Regardless of provenance, there is only one first, and it trumps provenance.

The most recent example of the Writing Ball to come to auction fetched US$200,000 in 2021, making it the second most valuable typewriter ever sold at auction, behind only Cormac McCarthy's Lettera 32 Olivetti portable.

The American novelist, playwright and screenwriter bought the Olivetti in 1963 for $50 and used it to type everything he wrote for 40 years (he estimated he'd typed 5 million words on it), winning a Pulitzer and a National Book Award along the way.

As often happens at auctions where the proceeds go to charity, the bidding got crazy, and an unidentified American collector paid $254,500, against a high estimate of $20,000. The proceeds of the sale were donated to the Santa Fe Institute, a nonprofit interdisciplinary scientific research organization. That also disqualifies it by our rules of not counting charity auctions – they're a wonderful thing but people don't act rationally at charity auctions and the results should be excluded from any data used to make financial decisions.

That means that the 1867 Malling-Hansen “Writing Ball” sold by Auction Team Breker on 25 September 2021 for €170,000 ($199,750) is the most expensive typewriter in history, nudging out Ernest Hemingway's $162,500 1926 Underwood Standard Portable, which produced The Fifth Column, To Have and Have Not, and For Whom the Bell Tolls. It's also the machine he would have carried onto the beaches of Normandy when he landed with the Allied forces on D-Day as a war correspondent.

His first attempt to land on Omaha Beach was aborted when Hemingway was close enough to see what he was missing. He later wrote on this machine, "the first, second, third, fourth and fifth waves of landing troops lay where they had fallen, looking like so many heavily laden bundles on the flat pebbly stretch between the sea and first cover." This typewriter saw a lot, as Hemingway spent his life following trouble around.

This same Hemingway typewriter apparently went within a whisker of becoming the most valuable of all time when Angelina Jolie put an $11,000 deposit on it at a $250,000 sale price, then changed her mind. It was apparently going to be a wedding present for her then forthcoming marriage to Brad Pitt.

Nominal equal second (but also disqualified - another charity auction) at the same $162,500 auction price was Playboy creator Hugh Hefner's Underwood Standard Portable which he used in college and in putting together the first copy of the magazine that would launch an empire and change societal standards forever.

Third place goes to the Williams No. 6 typewriter used by Mark Twain, which fetched $106,250 in 2024. If you can't afford a Malling-Hansen Writing Ball, check out his Williams typewriter, one of the most glorious mechanical devices ever conceived. John Newton Williams who designed the machine would later design, build and fly the world's first co-axial helicopter.

At the other end of the scale, typewriters will do your bidding no matter what they cost.

In closing, the specimen of the Malling-Hansen Writing Ball going to auction is one of five in private hands, and it already holds the world record.

The exquisitely beautiful Malling-Hansen Writing Ball which currently holds the record, did so without any known history - it did so without Ernest Hemingway or Mark Twain in its provenance.

That's why we'll be watching when the hammer comes down.

Source: Auktion Team Breker

Editor's note: this machine sold for EUR €188,913 (USD $205,141), breaking it's own world record