Perhaps one of the most pervasive longstanding technology conspiracy theories is that your smartphone is constantly listening in on your private conversations. Almost everyone at some point has felt the eerie synchronicity of seeing an ad served up on Facebook that exactly corresponds to a recent conversation. It’s certainly unnerving, and the most simple explanation is one of direct surveillance. Of course Facebook is listening in on your private conversation with friends, catching key words, and then serving you tailored advertisements. And of course Facebook would deny this is happening.

The problem is, outside of anecdotal cases, no one has ever been able to find clear evidence that this is actually happening. Mobile cybersecurity company Wandera recently conducted a series of experiments which again prove your smartphone is not consistently listening in to your private conversations. So, while this urban myth has again been debunked, the truth about how companies like Facebook sometimes serve up such disturbingly accurate advertisements turns out to be much more complex, and unsettling.

Facebook admits listening to private conversations

In early August 2019, Bloomberg News published a story revealing how Facebook had contracted an external company to transcribe audio conversations conducted through the Facebook Messenger app. The process was engaged to test the accuracy of an automatic transcription algorithm Facebook was rolling out, and the company claimed all users who opted in to the transcription service were aware of the potential human review system. While some reports questioned how transparent Facebook’s notification process actually was, the story rapidly spread across media outlets, with a vast of array of headlines dramatically affirming, “Facebook admits it was listening to your private conversations.”

To the average headline skimmer, whose primary knowledge of news comes from glancing across headlines that pop up in social media streams, this was enough to reanimate years of conspiratorial assumptions. The news story was akin to throwing gasoline on the burning embers of a myth that had been almost extinguished.

Even the media outlet that broke the original story made a somewhat disingenuous link between the old microphone-ad conspiracy and this new revelation, referencing Mark Zuckerberg’s testimony to US congress in April 2018 as if presenting a "gotcha" moment of lying. Responding to Senator Gary Peters who questioned whether Facebook listened in on user’s microphones to generate targeted ads, Zuckerberg replied, “You’re talking about this conspiracy theory that gets passed around that we listen to what’s going on on your microphone and use that for ads. We don’t do that.”

In fact, Facebook has been denying for years that it listens to user conversations to generate targeted ads. Way back in mid-2016 the company first tried to debunk that conspiracy.

“Facebook does not use your phone’s microphone to inform ads or to change what you see in News Feed. Some recent articles have suggested that we must be listening to people’s conversations in order to show them relevant ads. This is not true. We show ads based on people’s interests and other profile information – not what you’re talking out loud about.”

The data doesn't add up

Most recently Wandera, a mobile cyber-security company, set out to test the “phone-snooping” theory, saying its customers seem constantly worried about the issue. Wandera's experiment was pretty simple. Place an iPhone and a Samsung Galaxy in a room, then play an audio loop of pet food ads for 30 minutes a day, over three days.

User permissions for a large number of apps were all enabled, and the same experiment was performed, with the same phones, in a silent test room to act as a control. The experiment had two main goals. First, a number of apps were scanned following the experiment to ascertain whether pet food ads suddenly appeared in any streams. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the devices were closely examined to track data consumption, battery use, and background activity.

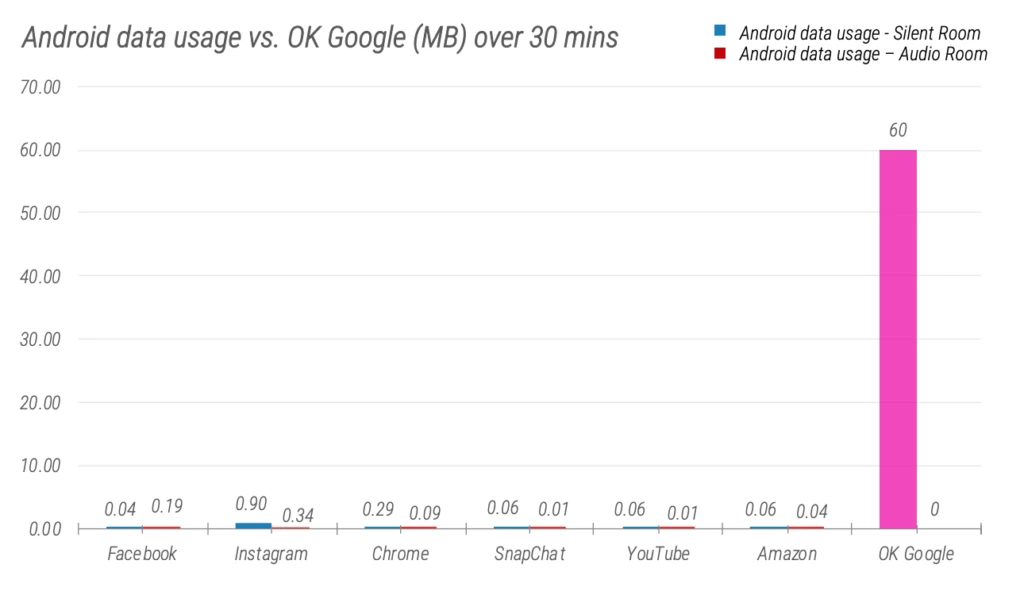

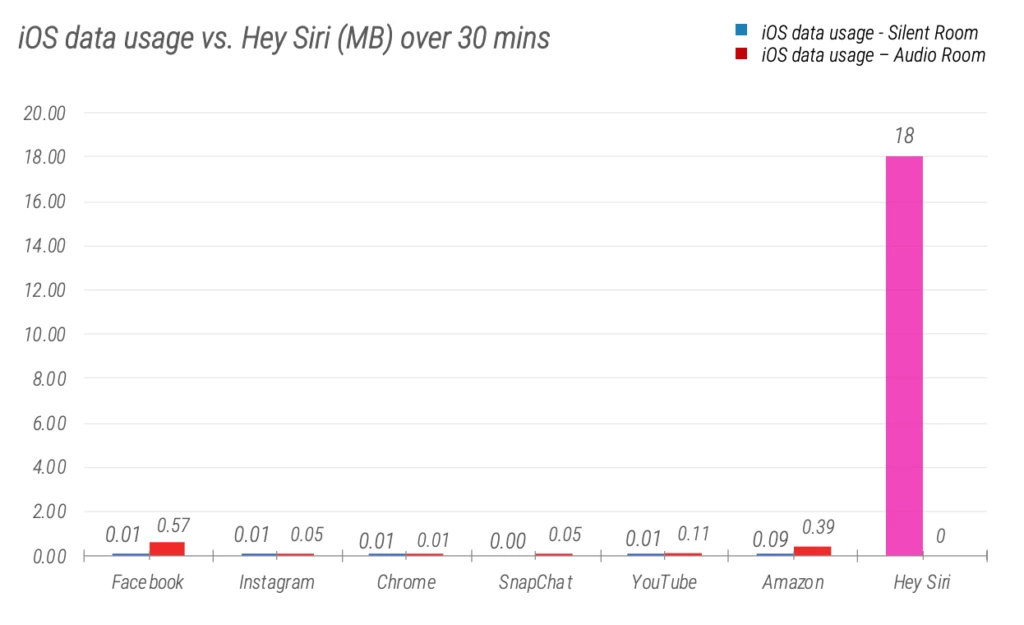

The results will probably surprise no one. No pet food advertisements showed up on any app following the test. Even more telling, there was virtually no difference in data consumption, battery use, and background activity between the audio room tests and the silent room tests. This fact is important, because if an app were accessing a microphone and sending the audio to a cloud server for analysis there would be notable traces of data consumption.

“We observed that the data from our tests is much lower than the virtual assistant data over the 30-minute time period, which suggests that the constant recording of conversations and uploading to the cloud is not happening on any of these tested apps,” says James Mack, a Wandera engineer working on the test. “If it was, we’d expect data usage to be as high as the virtual assistants’ data consumption.”

The lack of evidence of any data consumption in these tests is probably the most significant smoking gun debunking the longstanding myth. Antonio Garcia-Martinez, an ex-Facebook product manager, has been vocally critical of the company for several years after leaving it in 2013. However, in 2017 he penned an incredibly succinct editorial for Wired summing up why Facebook isn’t listening to you through your smartphone microphone. Like Wandera, Garcia-Martinez suggests the level of data consumption needed for microphone surveillance would make the technique not only improbable to execute, but also virtually impossible to hide.

"To make it happen, Facebook would need to record everything your phone hears while it's on,” Garcia-Martinez writes. “This is functionally equivalent to an always-on phone call from you to Facebook. Your average voice-over-internet call takes something like 24 kbps one way, which amounts to about 3 kBs of data per second. Assume you've got your phone on half the day, that's about 130 MBs per day, per user. There are around 150 million daily active users in the US, so that's about 20 petabytes per day, just in the US. To put that in perspective, Facebook's entire data storage is 'only' about 300 petabytes, with a daily ingestion rate of about 600 terabytes.”

Some counter that argument by suggesting Facebook can simply scan audio for keywords coming into the microphone on a device. This means it wouldn’t need to constantly stream an open audio channel from your microphone into the cloud. But Garcia-Martinez also pushes back on that idea suggesting not only does Facebook have millions of targeted ad keywords it would need to track, but the strain on your phone’s CPU would be immediately noticeable. And again, nearly impossible to hide.

"Then we started seeing things we didn't expect"

In early 2017 Jingjing Ren, a PhD student at Northeastern University, and Elleen Pan, an undergraduate student, designed a study to investigate the very issue of whether phones listen in on conversations without users knowing. Pretty quickly it became clear to the researchers that the phone’s microphones were not being covertly activated, but it also became clear there were a number of other disconcerting things going on.

“There were no audio leaks at all – not a single app activated the microphone,” says Christo Wilson, a computer scientist working on the project. “Then we started seeing things we didn’t expect. Apps were automatically taking screenshots of themselves and sending them to third parties. In one case, the app took video of the screen activity and sent that information to a third party.”

Out of over 17,000 Android apps examined, more than 9,000 had potential permissions to take screenshots. And a number of apps were found to actively be doing so, taking screenshots and sending them to third party sources.

“That has the potential to be much worse than having the camera taking pictures of the ceiling or the microphone recording pointless conversations,” says David Choffnes, another computer scientists working on the project. “There is no easy way to close this privacy opening.”

So, your phone may not be listening in to your conversations, but it has the capacity to track you in so many other ways. And it is this massive trove of trackable data that is how companies like Facebook are able to serve you targeted ads that occasionally seem frighteningly accurate.

“Everything that makes your phone useful, like knowing where you are, taking photos, enabling online shopping and banking – these are exactly where the potential weaknesses and vulnerabilities are,” says Mike Campin, VP of engineering at Wandera. “The more useful your phone is, the more attractive it is to advertisers, hackers, or anyone who wants your data.”

And it is here where the truth behind Facebook’s occasionally unsettlingly targeted ads becomes much more creepy than any microphone surveillance conspiracy theory.

The harsh truth

“The harsh truth is that Facebook doesn’t need to perform technical miracles to target you via weak signals. It’s got much better ways to do so already,” writes Garcia-Martinez. “Not every spookily accurate ad you see is a pure figment of your cognitive biases. Remember, Facebook can find you on whatever device you’ve ever checked Facebook on. It can exploit everything that retailers know about you, and even sometimes track your in-store, cash-only purchases; that loyalty discount card is tied to a phone number or email for a reason.”

So you may adamantly claim Facebook must have listened in on your private conversation yesterday about a friend’s wedding and then served you an ad for tailored wedding suits because you have not googled anything wedding-related in years. But there are scores of other data points the system has on you to determine what you should see at any given point. Not only does the system know exactly where you are at every moment, it knows who your friends are, what they are interested in, and who you are spending time with. It can track you across all your devices, log call and text metadata on Android phones, and even watch you write something that you end up deleting and never actually send.

The deeply disconcerting implication of all this is that the rich vein of data constantly being gathered can be crunched by an algorithm to essentially predict what you and your friends are talking about, and serve you an ad that is perfectly tailored to your current needs. Even though these Facebook ad algorithms are not nearly perfect (try to pay attention to how often you are served ads that are entirely irrelevant to your interests), the simple fact that they are so eerily correct even some of the time is the real conspiracy here.

It is almost impossible for a human mind to understand how these complex algorithms work. How they crunch vast volumes of person data to decide now is the right time to serve up an ad for fried chicken is possibly beyond the comprehension of even the engineers designing the algorithms. In many ways, it makes sense so many people still believe in the microphone conspiracy. It is so much easier to understand how Facebook served you up that prescient ad if we imagine it simply overheard the conversation you had yesterday with friends. But as with many things in life, the truth happens to be much more complicated, much more inscrutable, and much more disturbing.