Inflated balloons that trick the stomach into feeling full have long been used for weight loss. The problem is that they become less effective the longer they stay inflated. Now, MIT engineers have devised a balloon that inflates and deflates on demand – and it reduced food intake by 60%.

It’s trite to say that obesity is a global problem that contributes to the morbidity and mortality of millions. The widespread popularity of injectable anti-obesity medications would seem to indicate that many people already know this. However, those who can’t take these drugs because of their side effects or expense need an effective weight loss alternative.

An inflated balloon that occupies stomach space, producing a continuous feeling of fullness to curb overeating, is not a new weight loss method. However, the effectiveness of this approach can wane over time because the balloon is always inflated. Now, MIT engineers have outlined in a new study how they’ve devised a gastric balloon that can be inflated and deflated as needed.

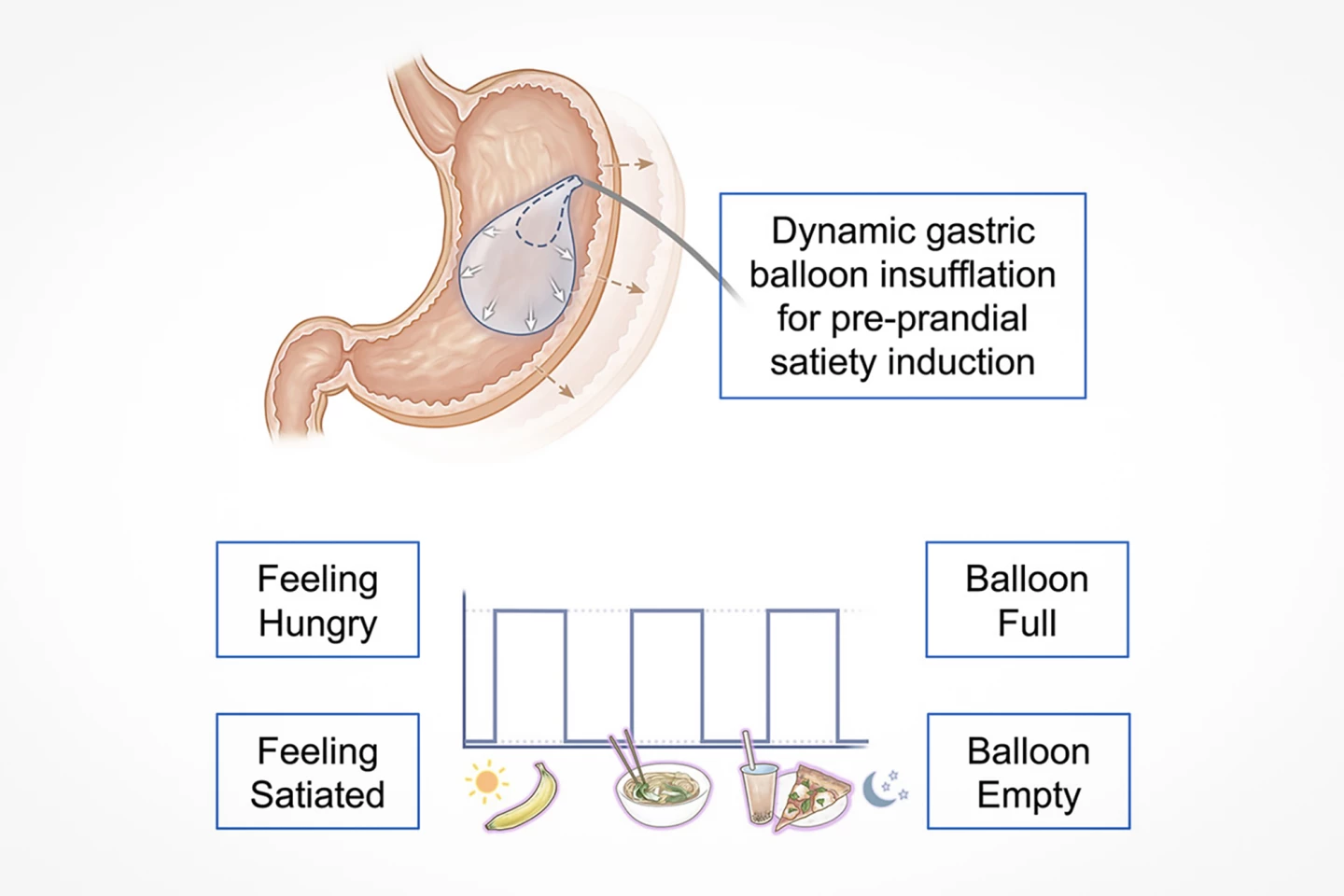

“Gastric balloons do work initially,” said Giovanni Traverso, an associate professor of engineering at MIT, a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the study’s corresponding author. “Historically, what has been seen is that the balloon is associated with weight loss. But then, in general, the weight gain resumes the same trajectory. What we reasoned was perhaps if we had a system that simulates that fullness in a transient way, meaning right before a meal, that could be a way of inducing weight loss.”

Research has shown that while intragastric balloon (IGB) therapy offers a minimally invasive method of losing weight, its effectiveness decreases about three or four months after placement. This is because if the balloon’s size is not made incrementally larger, the stomach adapts to its presence and stops sending its satiety signals to the brain. As a result, weight loss plateaus. It’s simply explained in the video above for a brand of commercially available adjustable gastric balloon called the Spatz3.

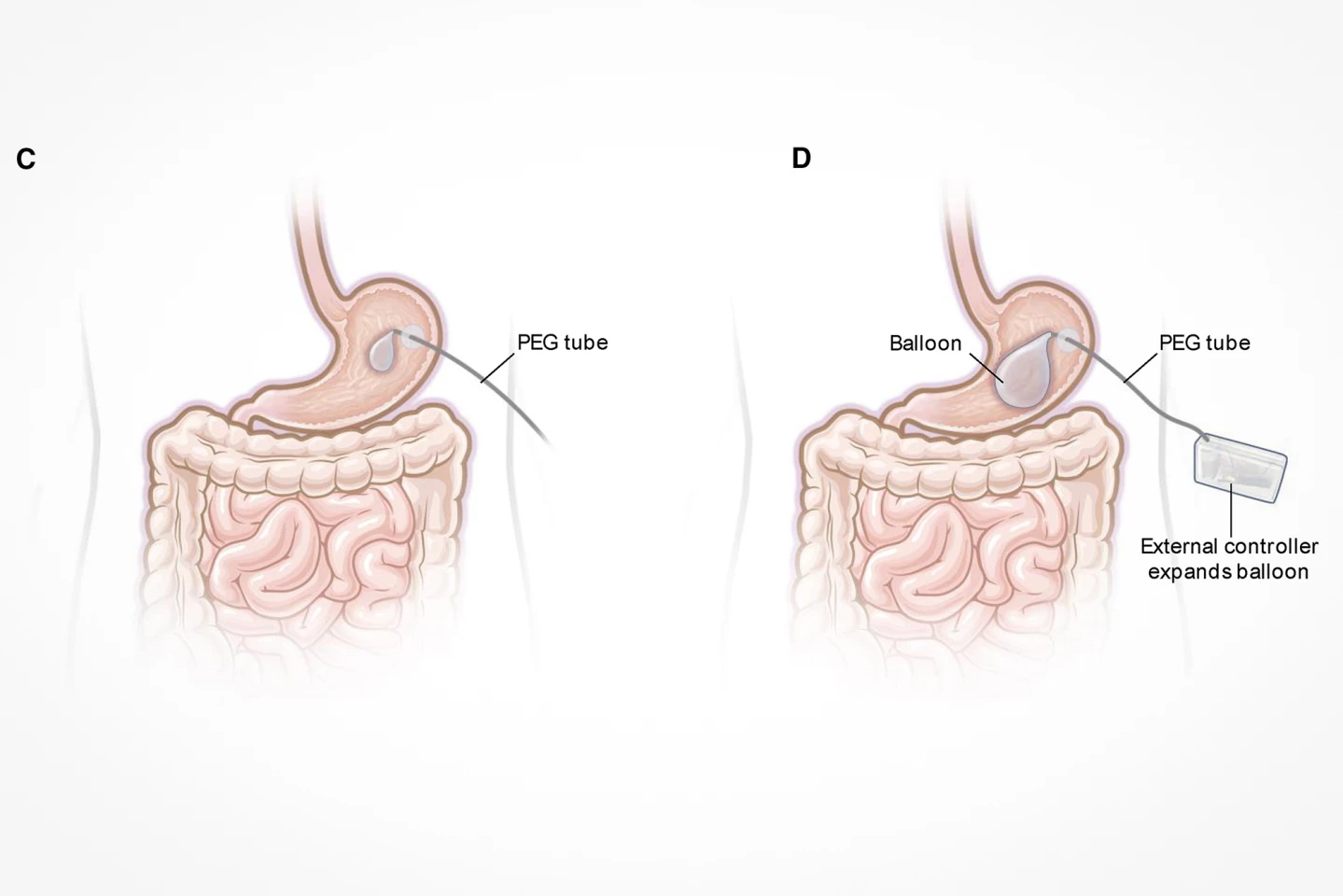

The MIT engineers’ goal was to improve upon the Spatz3, which can only be adjusted upward – that is, made larger. So, they devised the oscillating satiety induction and regulation intragastric system, or OSIRIS. The OSIRIS balloon is inflated pre-meal to stimulate a feeling of fullness and then deflated afterwards to reduce the risk that the stomach will become accustomed to the inflated balloon. The on-demand inflation-deflation cycle, which is achieved using a printed circuit board, happens three times a day: at breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

“The basic concept is we can have this balloon that is dynamic, so it would be inflated right before a meal, and then you wouldn’t feel hungry,” Traverso said. “Then it would be deflated in between meals.”

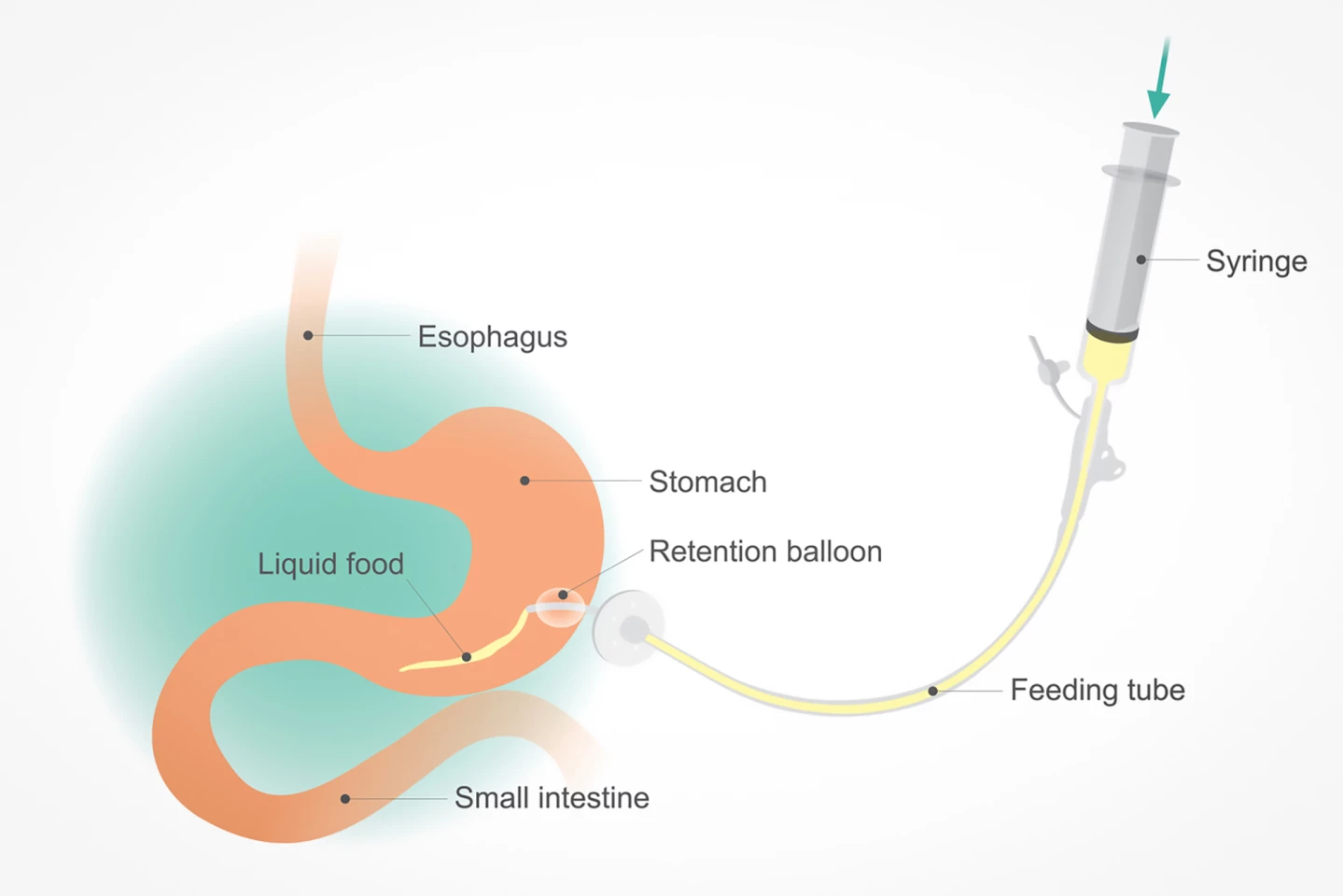

At present, many IGB designs exist with little difference between them, few of which have been approved by the FDA. Most require insertion using an endoscope, which passes the deflated balloon through the mouth, down the esophagus, and into the stomach. There, the balloon’s inflated with either liquid or gas to cause the mechanical distension needed for a continuous sensation of satiety. While IGB insertion is minimally invasive and can be done as an outpatient procedure, it requires the use of general anesthesia.

At the other end of the spectrum of obesity treatments in terms of their invasiveness is bariatric surgery. That’s the umbrella term for a variety of procedures that achieve weight loss by surgically altering the size and anatomy of the stomach to limit food intake or, in some cases, change the digestive process to improve fat metabolism. Bariatric surgery is a major surgery, so it comes with associated risks and complications. And, obesity in and of itself increases risk when undergoing surgery.

The OSIRIS system is closer to the IGB on the invasiveness spectrum. A PVC balloon is delivered endoscopically, like a traditional gastric balloon. A tube is inserted directly into the stomach through the skin of the abdomen to act as the means of inflation and deflation of the balloon. It’s inserted the same way as a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube is in someone who’s unable to eat or drink to provide them with liquid nutrition. PEG insertion uses only moderate sedation along with local anesthesia, so it’s not considered a major surgery. In addition to its minimally invasive insertion, the researchers see other benefits to using a PEG tube.

“If people, for example, are unable to swallow, they receive food through a tube like this,” Traverso explains. “We know that we can keep tubes in for years, so there is already precedent for other systems that can stay in the body for a very long time. That gives us some confidence in the longer-term compatibility of this system.”

The researchers evaluated the effectiveness of the OSIRIS system on three groups of pigs. One group acted as a control (no balloon), one as a sham (the balloon was uninflated), and the third was the treatment group (inflated device). The pigs were fed 1,360 g of pellet feed twice a day for a 30-minute period, and the remaining feed was weighed after each feeding episode. Inflating the balloon before meals caused a remarkable 60% reduction in the animals’ food intake.

Preliminary testing of the OSIRIS system occurred over a short time – the course of a month – so the next step for the researchers is to evaluate the device over a longer period to see if the reduction in food intake leads to weight loss.

“The deployment for traditional gastric balloons is usually six months, if not more, and only then you will see [a] good amount of weight loss,” said Neil Zixun Jia, a recent MIT PhD graduate and the study’s lead author. “We will have to evaluate our device in a similar or longer time span to prove it really works better.”

If the OSIRIS system can be safely transitioned to human use, it would offer an alternative weight loss option that is slightly more invasive than injectable anti-obesity medications but far less invasive (and risky) than bariatric surgery.

“For certain patients who are higher risk, who cannot undergo surgery, or did not tolerate the medication or had some other contraindication, there are limited options [for weight loss],” said Traverso. “Traditional gastric balloons are still being used, but they come with a caveat that eventually the weight loss can plateau, so this is a way of trying to address that fundamental limitation.”

The study was published in the journal Device.

Source: MIT