Following on from a remarkable study in mice, scientists have now confirmed that silencing a certain protein in muscle tissue leads to energy-deprived human cells seeking out fat for fuel, while blocking the body's ability to store extra fat cells.

Researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science are now one step closer to a new way to target obesity without it effecting muscle mass, which is something that unfortunately the suite of GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs do negatively impact. The team has found that silencing MTCH2 protein expression in muscle tissue, which was first demonstrated in mice, also made human cells essentially "immune" to storing fat and supercharged metabolism naturally.

MTCH2, which has been cutely dubbed "Mitch," even ramped up muscle function and performance – described by the scientists as increased athletic ability – delivering that elusive outcome of diet-free, gym-free fat loss and improved health and fitness.

It's the latest discovery in an emerging area of obesity research focused on the expression of proteins. Earlier this year, a study detailed how silencing another protein – the liver's plasmalemma vesicle-associated protein – could also switch fuel sources to be more efficient at burning fat sources and speed up metabolism. In 2018, another study showed how switching off a different gene would have a similar outcome.

And in January, scientists found that tweaking the BCL6 protein, which plays a key role in muscle structure, could also burn fat while improving tissue structure without a single day of weight training.

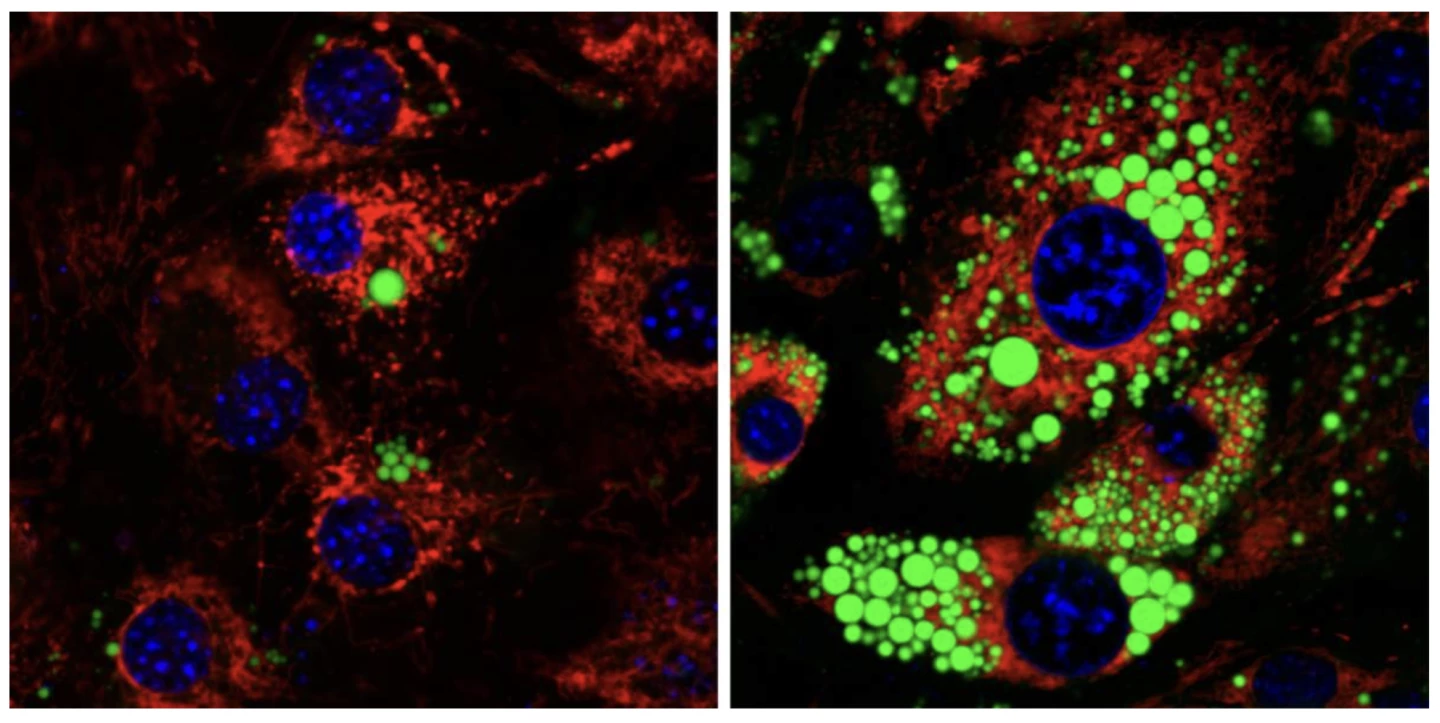

In the latest study, the team found that shutting down Mitch had the same effect on human cells as previously seen in mice. Without this protein, fats and carbohydrates were burned at a higher rate, and it appeared to block new fat cells from developing.

What's perhaps most interesting about Mitch's origin story is that it plays a key role in mitochondrial fusion – which is a process that guides the union of two previously distinct organelles within a cell. We all know from biology class that mitochondria are the "powerhouse" of the cell, crucial in converting fuel to energy. So in blocking Mitch, cells are deprived of efficient energy production. But rather than prove harmful, it simply forced the cells to seek out other energy supplies to accommodate for the deficit. And, unlike the go-to source of carbohydrates and proteins, the go-to alternative energy was deposited fat.

"After deleting Mitch, we examined, every few hours, the effect that it had on more than 100 substances taking part in metabolism in human cells," said lead researcher Sabita Chourasia. "We saw an increase in cellular respiration, the process in which the cell produces energy from nutrients, such as carbohydrates and fats, using oxygen. This explains the increase in muscular endurance in previous experiments using mice."

While it sounds a little counter-intuitive, the Mitch-free cells didn't starve without mitochondrial fusion – they just developed an appetite for fat. Carbs are generally the preferred source of fuel, as they're easily accessible and quick to process, fat is more energy dense, so a better target for energy-deprived cells.

"We discovered that deleting Mitch led to a major drop in fats in membranes," said Weizmann professor Atan Gross. "At the same time, we saw an increase in fatty substances used to produce energy, and we realized that the fat was being broken down from the membrane to be used as fuel. In other words, we showed that Mitch determines the fate of fat in human cells."

What's more, the scientists found that Mitch – which has been shown to be elevated in obese women – also plays a key role in determining what kind of fat deposits develop as progenitor cells become mature fat cells.

"When we deleted Mitch from the progenitor cells, we discovered that the environment created in these cells was not conducive to the synthesis of new fats," Gross said. "Reducing the ability to synthesize membranes prevents the cells from growing, developing and reaching the point where differentiation is possible."

Essentially, without Mitch, the muscles develop a kind of "obesity immunity," which is made even stronger thanks to the switch in metabolic function that sees cells seeking out fat to burn for energy.

"The process of fat accumulation requires a large amount of available energy, but in cells without Mitch, there is a shortage of energy," said Gross. "In addition, the expression of genes necessary for differentiation is suppressed, and there is a shortage of the substances vital for this process to occur. As a result, differentiation of new fat cells is reduced, along with fat accumulation."

With a better understanding of the role Mitch plays in blocking fat accumulation, the researchers are now working on developing a new small molecule therapeutic that could silence Mitch. If successful, this could have a profound impact on weight loss and obesity treatment.

The research was published in The EMBO Journal.

Source: Weizmann Institute of Science