There are ongoing moral and ethical battles concerning the farming and application of human embryonic stem cells in medical research and applications. Without judging any of the viewpoints represented in the fracas, it is clear that the stem cell world would be a friendlier place if the harvesting of embryonic stem cells were not necessary. Toward this goal, Johns Hopkins scientists have developed a reliable method to turn the clock back on blood cells, restoring them to a primitive stem cell state from which they can then develop into any other type of cell in the body.

The new Johns Hopkins technique regresses blood cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) – able to make any type of bodily cell, but not able to form a new embryo (that would require forming totipotent stem cells, which are also capable of growing into the tissue of the placenta). This means there are no ethical problems involving human cloning in this procedure. In addition, as the iPS will be generated from your own blood cells, there should be no genetic mismatches that could lead to tissue rejection.

Wait a minute, though – human red blood cells deliver oxygen throughout the body, but have no cell nucleus and no DNA. How can they be regressed into a pluripotent stem cell that has your complete DNA? Therein lies the tricky part.

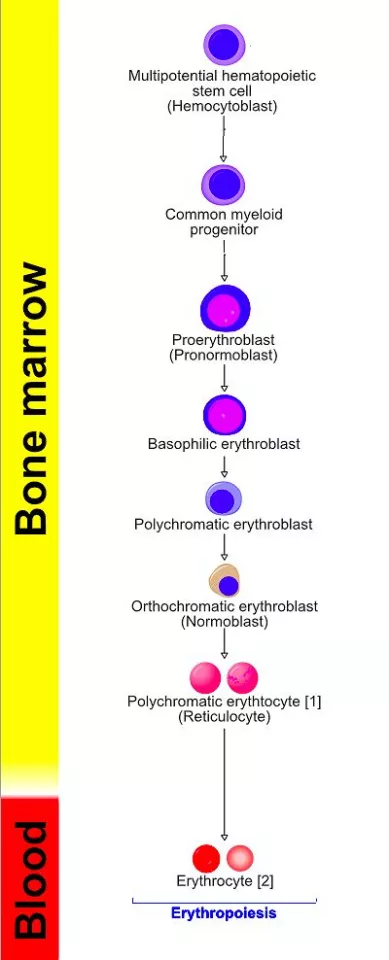

Red blood cells do not simply appear fully grown without a nucleus. During the process of erythropoiesis, or production of red blood cells (erythrocytes), there are many stages of development. Red blood cell production begins with a hemocytoblast stem cell (HSC), which is multipotent and able to develop into any of the cells found in blood as well as lymphoid tissues. HSCs are found primarily in the bone marrow, but can escape into the bloodstream or colonize the liver or spleen.

The following steps take the HSCs into mature red cells:

- 1. An HSC develops into a more restricted multipotent myeloid progenitor stem cell (MPSC), which, although still multipotent, can only develop into the various types of blood cells

Throughout most of the process of red blood cell generation, the cells do have a complete nucleus, and would be candidates for regression into pluripotent stem cells. Common wisdom in the field suggests that it would be easiest to regress multipotent hematopoietic stem cells to an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS), as it has undergone the smallest degree of differentiation therefrom. However, the Johns Hopkins team found that beginning with LCSCs gave far more positive results, with 50-60 percent of LCSCs regressing into iPS's, compared to far less than one percent of HSCs.

According to Elias Zambidis, assistant professor of oncology and pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Cell Engineering and the Kimmel Cancer Center, this new work is part of an ongoing effort to efficiently and consistently convert adult blood cells into stem cells that are highly qualified for clinical and research use in place of human embryonic stem cells.

“Taking a cell from an adult and converting it all the way back to the way it was when that person was a six-day-old embryo creates a completely new biology toward our understanding of how cells age and what happens when things go wrong, as in cancer development,” Zambidis says.

Zambidis and his team have managed to develop a rapid and efficient way to make iPS cells, overcoming a persistent difficulty for scientists working with these cells in the laboratory. Generally, out of hundreds of blood cells, only one or two might turn into iPS cells. Using Zambidis’ method, 50 to 60 percent of blood cells were engineered into iPS cells.

One requirement for regressing stem cells is to insert certain combinations of genes into the LSCS – in this case four genes called the Yamanaka factor. The Johns Hopkins team have introduced a new way to insert those four genes into the LSCS cells.

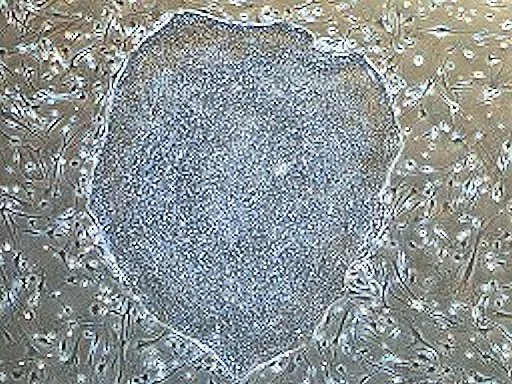

Viruses are generally used to insert a package of genes to turn on processes that convert cells back to stem cell states. However, viruses used in this way can mutate genes and initiate cancers in newly transformed cells. To insert the genes without using a virus, Zambidis’ team used plasmids, rings of DNA that replicate briefly inside cells and then degrade. The plasmids were delivered by electroporation, that is, by applying an electrical pulse to the cells, making tiny holes in the surface through which the plasmids could slip inside. Once inside, the plasmids triggered the cells to revert to a more primitive cell state. The blood cells were also given an additional new step in which they were stimulated within their natural bone-marrow environment.

When iPS cells from various sources were compared, the "best" iPS cells were regressed from LSCS treated with the four-gene plasmid, and cultured with bone marrow cells. These cells converted to a primitive stem cell state within seven to 14 days. Their techniques also were successful in experiments with blood cells from adult bone marrow and from circulating blood.

In ongoing studies, Zambidis and colleagues are testing the quality of the newly formed iPS cells and their ability to convert to other cell types, as compared with iPS cells made by other methods. If they live up to their early performance, the field of stem cell therapy may be able to shift from debatable possibility to welcomed fact.

Source: Johns Hopkins University