Australia has a lot of sun and desert space, positioning the country well to continue being an energy exporter in the net zero era. But the renewable assets it'll need to build to get there are absolutely epic in scale, according to a new report.

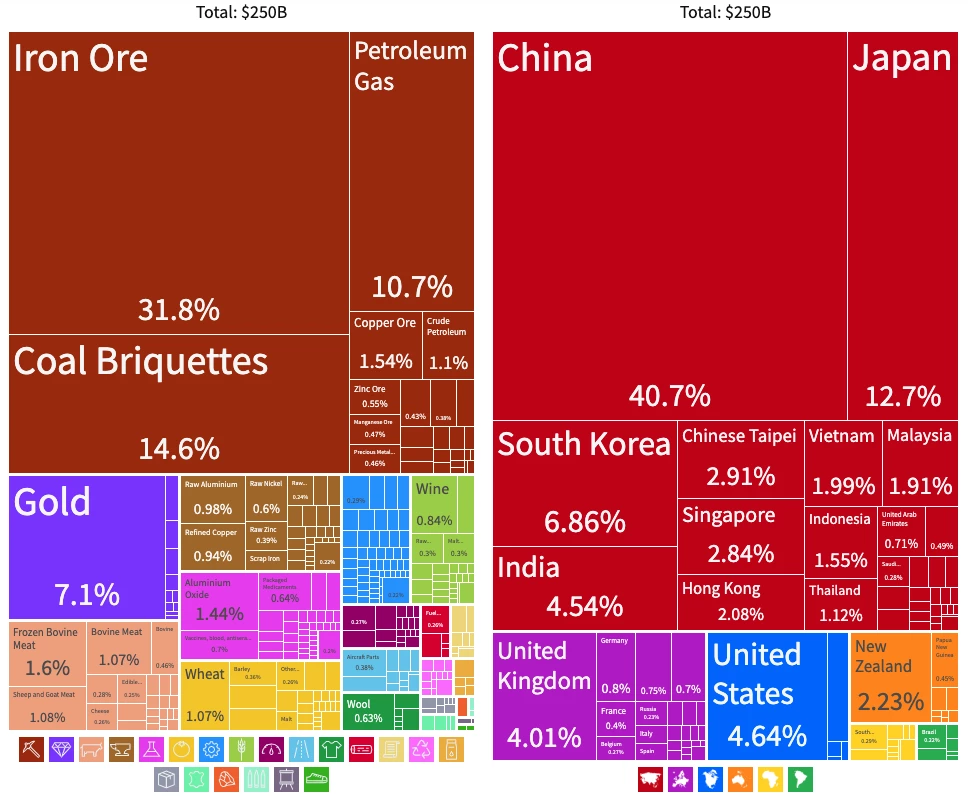

The country has long sustained its economy on natural resources. Its number one commodity is iron ore, representing nearly a third of all exports, but its coal and gas sales into Asia and India make up a further quarter of the country's export profile. These dirty fossil fuel dollars have an expiry date on them, but the country's huge expanses of hot desert represent an opportunity both to power Australia itself, and to replace coal and gas exports with renewably generated clean fuels.

So what does that look like? A Net Zero Australia research partnership between the University of Melbourne, University of Queensland, Princeton University and the Nous Group consultancy has put together a range of possible scenarios for 2050 – when both the federal government and the states have committed to net-zero domestic emissions.

The group's first interim report indicates that even in the absence of advanced nuclear power, renewables will produce enough energy for domestic use, creating between 1-1.3 million new jobs, primarily in the north of the country.

Domestic energy demand is surprisingly projected to decline slightly, rather than rising with expected population growth, due to the efficiencies gained through electrification. And much more investment in energy will be required – 50-70% more than sticking with fossil fuels, although the report notes that the costs of inaction on this front would be "substantial."

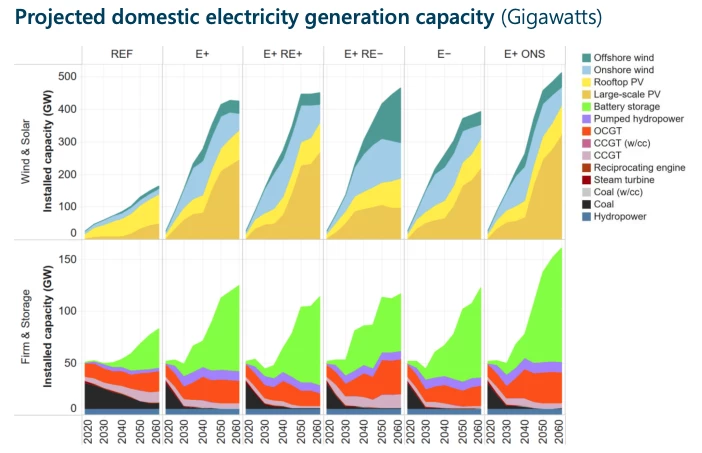

In all the group's scenarios, commercial-scale solar arrays and battery storage will need to ramp up sharply, and some level of carbon capture and storage will be needed to offset sectors like agriculture, which will not be possible to fully decarbonize.

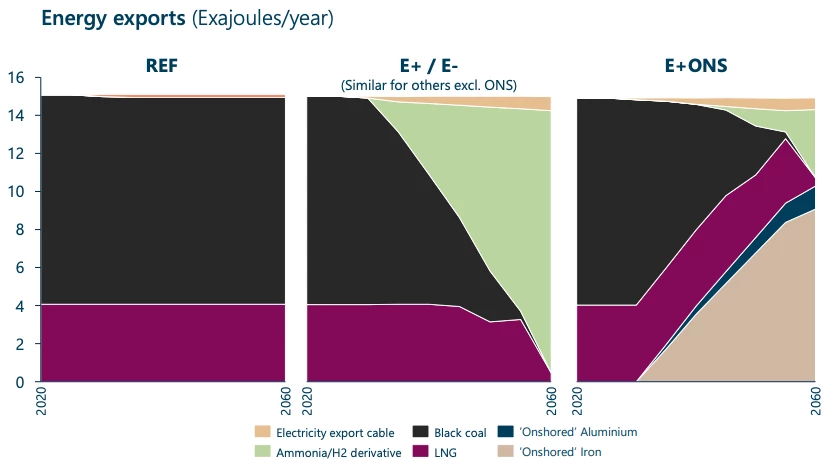

The country's 15-odd exajoules' worth of energy exports will need to move to hydrogen derivatives, chiefly ammonia unless cheaper storage and transport options are developed to commercial scale. The report finds that Australia should be able to compete with other exporters despite its geographical isolation.

And there's an opportunity for the country to start processing its own iron and aluminum ores onshore using renewable energy, to begin exporting clean refined metals – a value-added energy export, if you like, that could end up dwarfing straight clean fuel exports in terms of income.

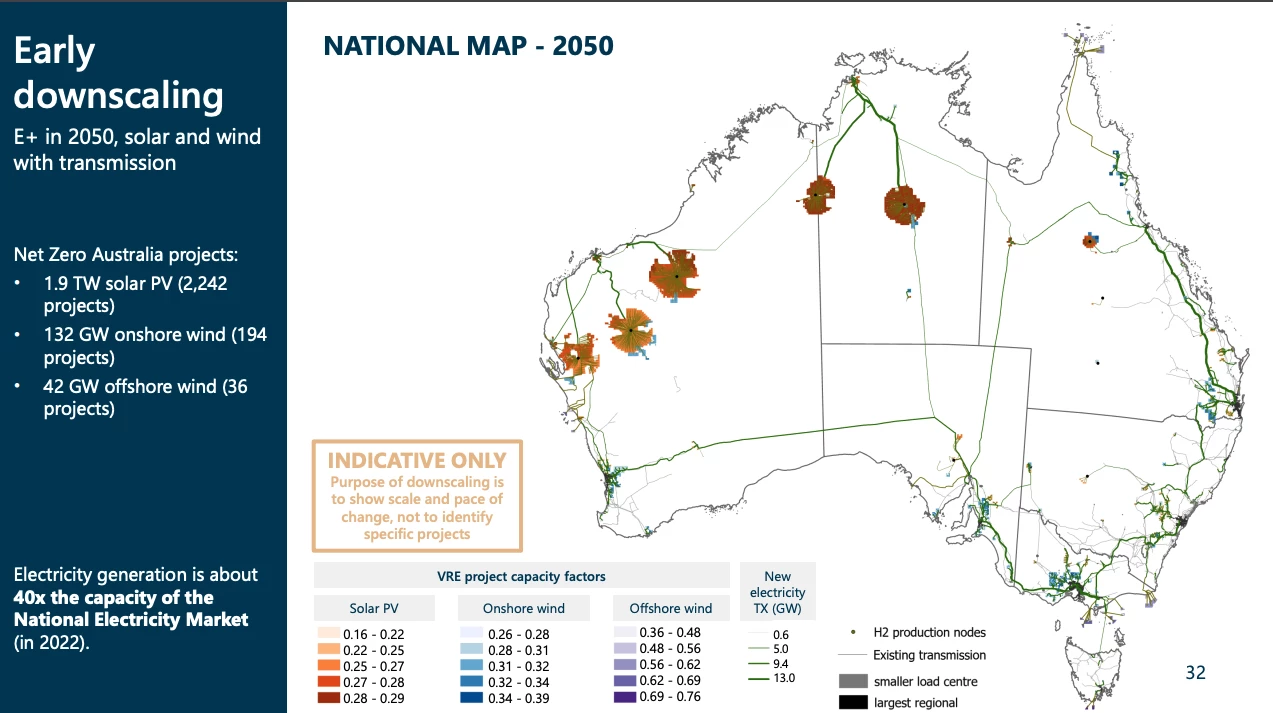

But as big as the opportunities are in this space, the scale of the renewable energy projects required – particularly the solar arrays – boggles the mind. To replace its current energy exports, the report estimates Australia will need to build out renewables to around 40 times the capacity of today's entire national energy market.

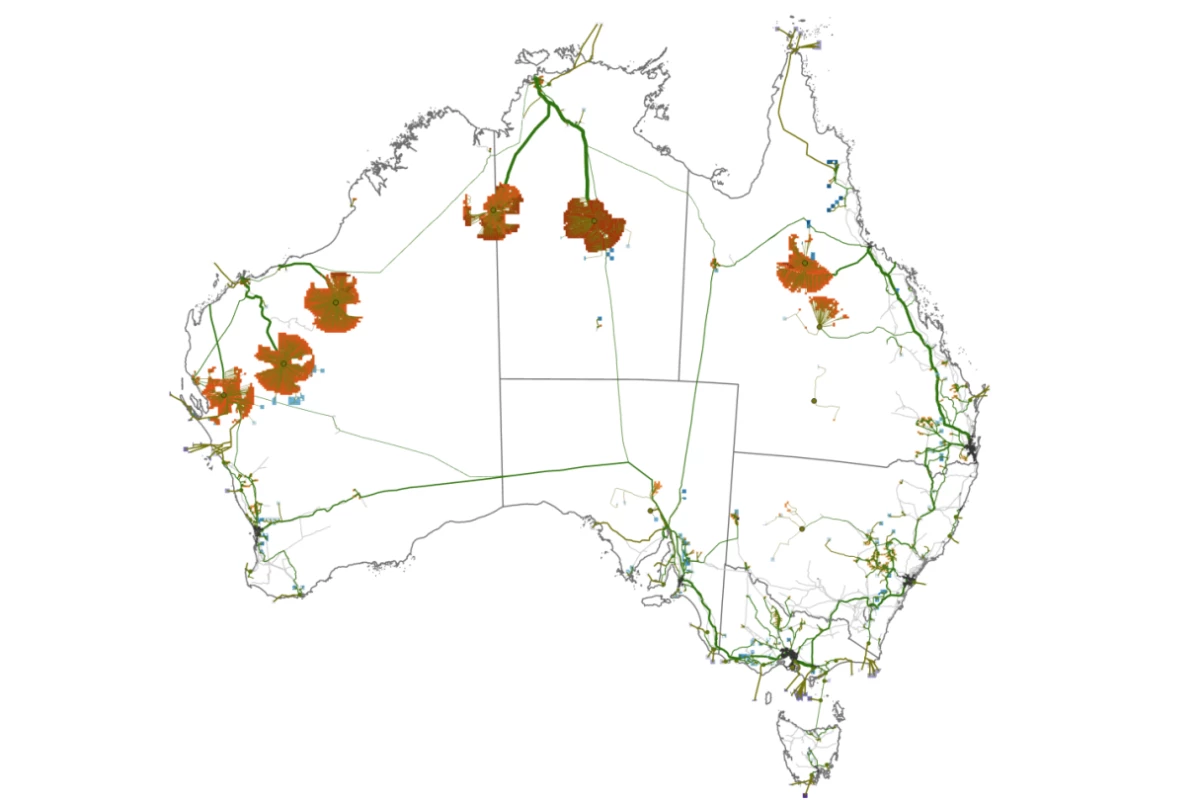

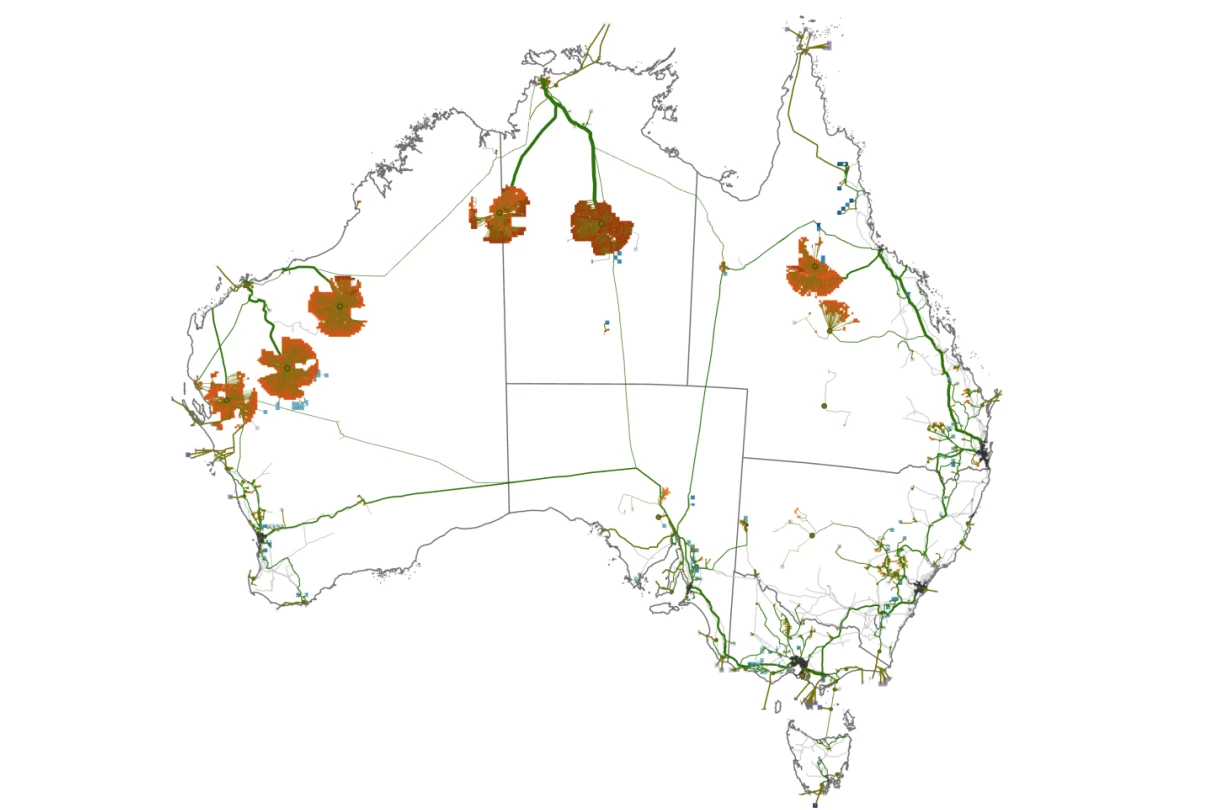

That'll require some 132 GW of onshore wind, 42 GW of offshore wind, and a monstrous 1.9 TW of solar photovoltaic projects. Net Zero Australia sketches out an indication of what that might look like on the map: five solar mega-projects, each nearly the size of the island of Tasmania. For reference, Australia is quite close to the size of the contiguous United States, so you could say that each of these solar projects might end up covering a land mass about as big as Alabama.

The challenges will be enormous. The materials, manpower and logistics involved in installations this size, plus all the electrolysis, processing and transport infrastructure must all be undertaken at extraordinary scale.

The environmental impacts can't be ignored, either – hydrogen electrolysis requires fresh water (or potentially atmospheric moisture), and exports at this scale effectively represent a shipping out of fresh water from a country famously prone to extended droughts. It's unclear what such a huge amount of shade might do to desert ecosystems, as well.

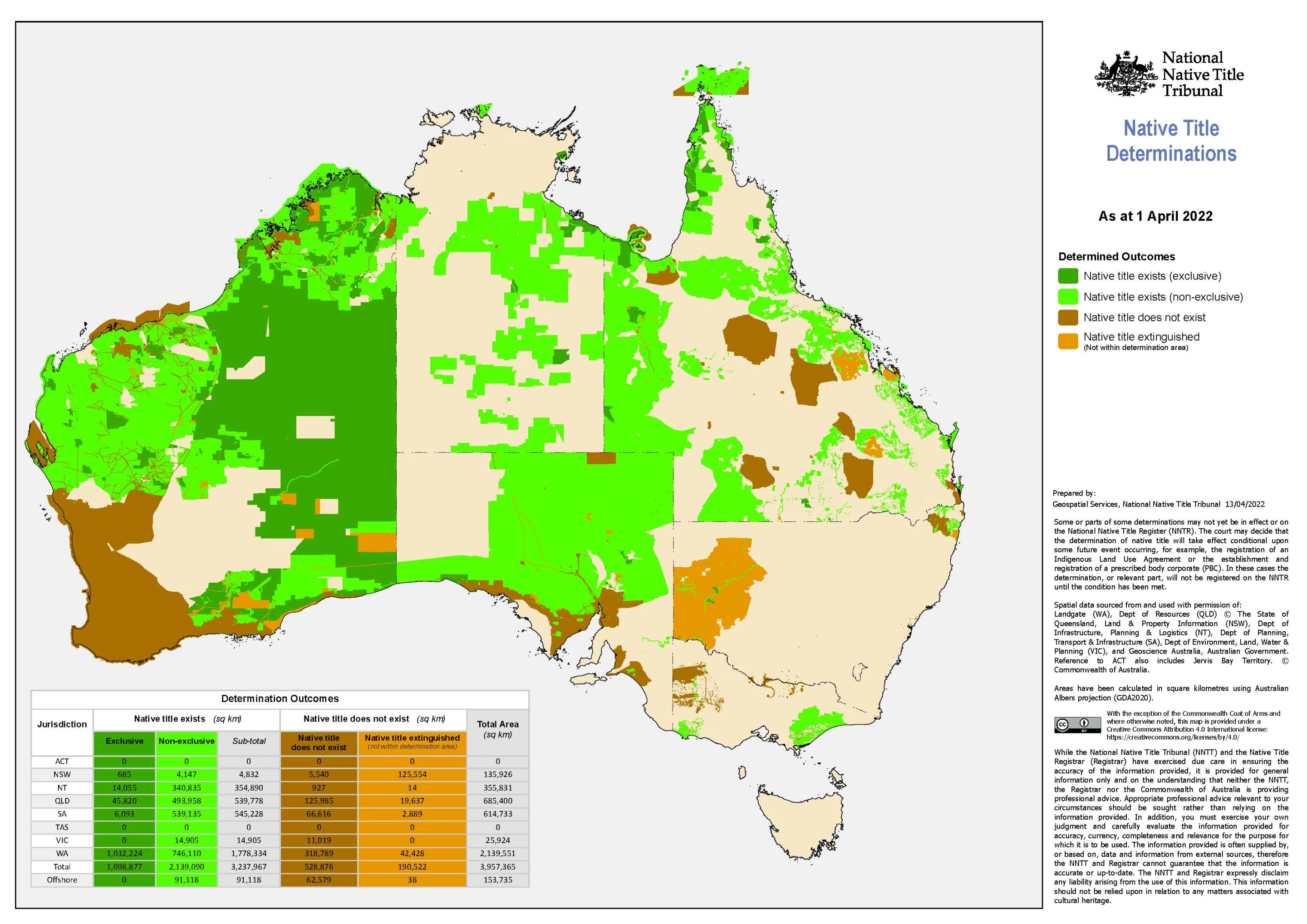

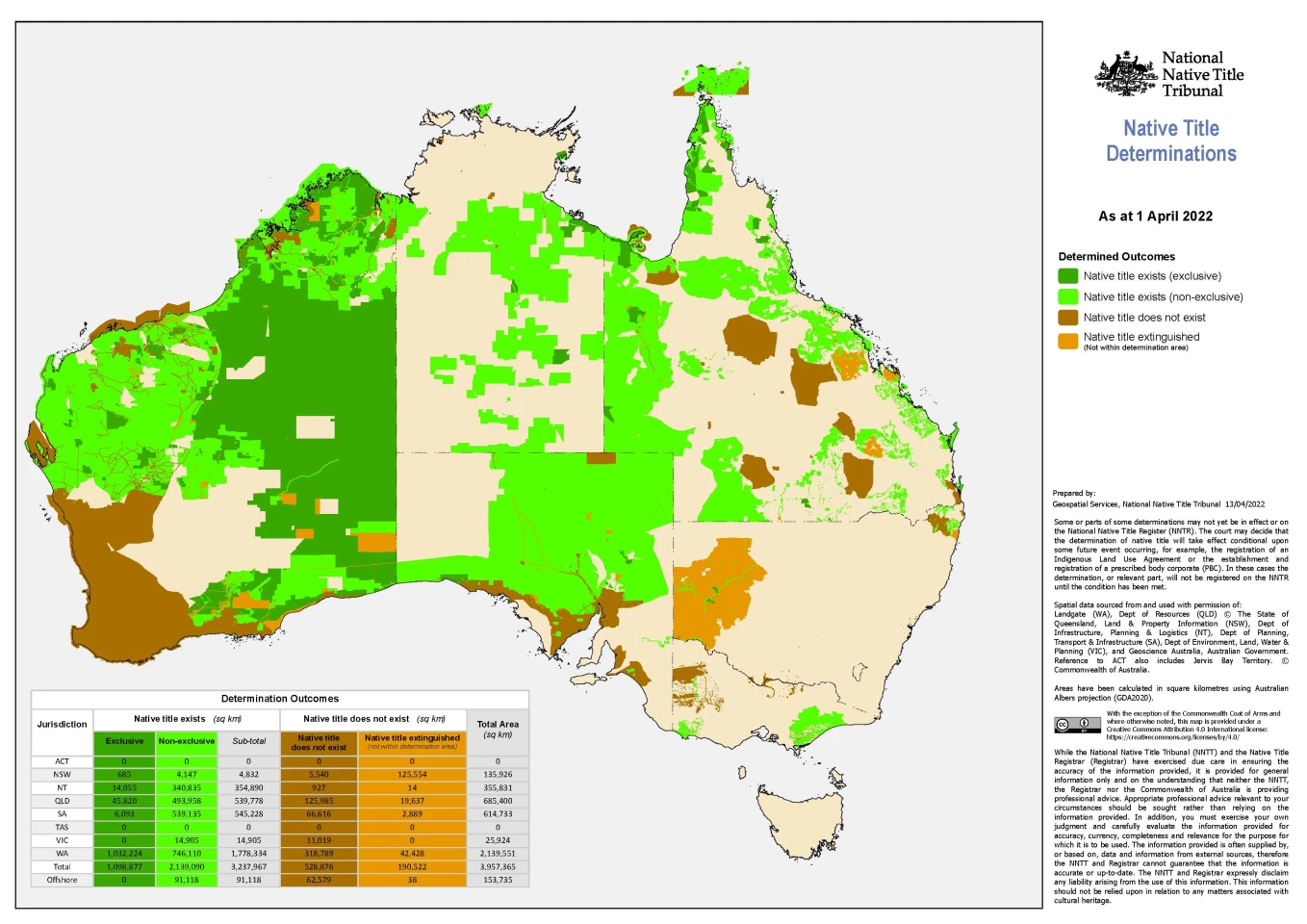

Not to mention native title; these enormous areas of land might look largely unoccupied, but Aboriginal groups were using the "empty" parts of the country for tens of thousands of years before European colonization in 1788, and these areas remain dotted with remote communities to this day. Native title and land rights legislation recognizing the displacement and dispossession of indigenous groups has created a complex system of ownership, negotiation and compensation rights that will absolutely be relevant to these solar megafarms.

The huge tracts of land in question will never be the same again. The country will bear the sleek, black barnacles of a clean energy transition in the same way as it now bears the scars of a mining economy.

Net Zero Australia's report is a fascinating look at the scope of the decarbonization challenge for a relatively small population living on a large land mass. Each country will have its own challenges, as well as enormous opportunities, and each must prevail.

Source: Net Zero Australia