Wave energy remains one of the least-exploited clean energy options, with huge potential as part of a green energy grid. Finland's AW Energy is preparing to field a contender at scale – the Waveroller – which sits on the sea bed generating up to 1 MW.

Wave power does not seem to be a super fast-moving sector. We've seen plenty of fascinating ideas in this space, from jetty-mounted pump arms, to telescoping barrels, to elastic sea-bed flappers, and two different flavors of artificial blowhole generators, to name just a few, but nearly all remain at a pilot/prototype stage.

Which is annoying; wave energy is super-reliable, super-predictable, and available 24/7 at coastlines worldwide, which is right where a lot of people tend to like living. It should be a dream addition to the renewable energy mix. But it's moving so slowly that you have to wonder where the holdup is.

The idea behind the Waveroller struck when a diver noticed a large hatch on a shipwreck moving back and forth with considerable power as waves passed over it, and wondered if the same "surge" effect, which causes water particles to move back and forth in horizontal elliptical shapes close to the shore, could be harnessed to drive a hydraulic piston and generate electricity.

That light bulb moment was in 1993, when Michael Jordan was cementing Charles Barkeley's legacy as a ringless wonder in the NBA Finals, and The Simpsons was hitting its stride in season five. We're talking "who needs a Quickie-Mart" and Homer joining a barbershop quartet. That long ago.

It took until 1999 to test a proof of concept, then until 2005 before small-scale test farms were installed in Scotland and Ecuador, then until 2016 to get a design manufactured, assembled, tested and certified around Europe. The first commercial WaveRoller, a 350-kW unit, was connected to the grid in 2019, 800 m (2,600 ft) off the Portuguese coast at Peniche. Here it is, brand spankers, being towed out and deployed.

Aaaand here it is, being pulled out for inspection two years later. Part of the problem might be fairly clear; the ocean is a harsh mistress. Anything you leave in there is battered by salt, eaten by corrosion and merrily settled by barnacles.

Mind you, AW Energy wasn't unhappy with this result: "We are delighted to confirm that the unit and its external components are in excellent condition, just take a look at the photo as proof of this system’s durability and quality," reads the company Facebook page from the day it was hauled ashore.

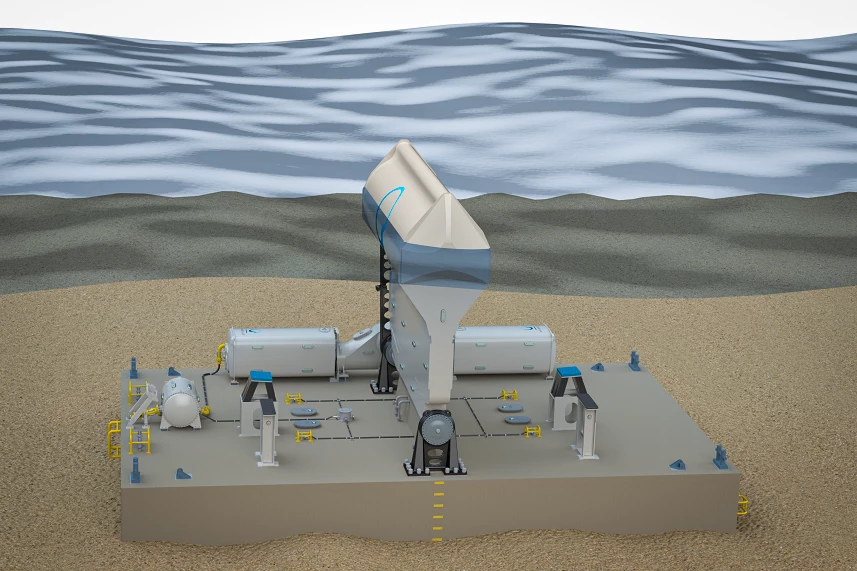

Since 2020, the company has worked on a project supported by EU funding, to adapt the WaveRoller and its associated bits and pieces for serial manufacturing, as well as for deployment in arrays of between 10-24 WaveRoller units. These arrays, called WaveFarms, will sit on the sea bed between 8 and 12 meters of depth, no further than 2 km (1.3 miles) from shore.

Each WaveRoller is rated for 1 MW of peak power production, and in a 2023 study published in Renewable Energy, we learn that each is expected to produce between 624-813 MWh per year. In terms of levelized cost of energy (LCoE), the WaveRoller comes out by far the most cost-competitive of the five technologies studied, with a LCoE of US$100-150/MWh.

That's well within reach of offshore wind, for comparison, which cost somewhere between US$82-255/MWh in 2022 according to the US DoE, and has enjoyed many years of commercial development to get costs into that ballpark.

Matthew Pech, CFO of AW-Energy, said in a press release that WaveRoller can “deliver electricity closer to baseload power than other renewables, and keep Europe at the forefront of innovative renewable technologies.” The WaveFarm project "enabled AW-Energy to take significant steps towards positive cash generation, both for the company and the European ocean energy sector, by readying the technology and the company for commercial deployment of the devices, and in developing the sales pipeline itself. ”

The company "envisions a global project pipeline of 150 MW for the WaveFarm solution," and "anticipates an addition of €275 million to the European economy and the creation of 500 jobs over the next decade."

Said pipeline is looking a tad bare as it stands; the company has signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with a clean energy company in Namibia, with a view to deploy a WaveFarm on the coast of Swakopmud. The MoU is a rather slippery document, worth more than a handshake but much less than a contract. That's about all we can find at this point, no matter how much the company is envisioning.

Forgive our impatience here, but we're gunning for cost-effective clean energy solutions that can bolster renewable power grids globally. It's been 31 years since the light bulb moment in this case, so how long's it going to be until waves are powering more actual light bulbs?

Sources: European Union, AW Energy