Two new studies by the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) are shedding new light on plastic waste in the Antarctic. Based on 30 years of extensive surveys of marine debris ingested by sea birds or washed up on Bird Island at South Georgia and Signy Island in the South Orkneys, researchers have been able to determine the source of plastics in the region and the effectiveness of mitigation efforts.

We like to think of Antarctica as a pristine, wild continent that's as untouched as a fresh snowfall, but its shores are still as exposed to the ocean's currents as anywhere else and often end up as repositories of plastic waste either brought in by waves or in the stomachs of seabirds.

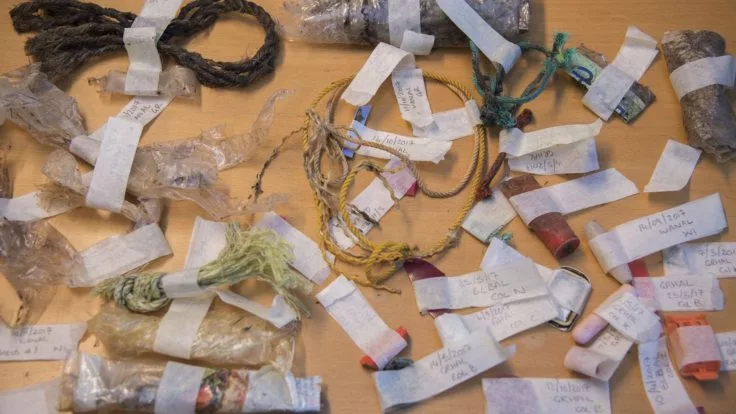

BAS has compiled extensive, continuous datasets over three decades to find out more about the nature and extent of plastic pollution in the Antarctic by collecting over 10,000 bits of flotsam and jetsam – most of which was plastic and included fishing gear and food wrappings.

In one study, a team led by BAS marine ecologist Claire Waluda discovered that the nature and quantity of the plastics recovered have changed over the years, along with evidence efforts to reduce the amount of debris entering the ocean have had a positive effect.

"While we found an increase in the quantity of beached plastic debris, recent surveys have shown increasing numbers of smaller pieces," says Waluda. "This might be due to the breakdown of larger pieces of plastic which have been in the Southern Ocean for a long time.

"It’s not all bad news. With the amount of plastic recovered on beaches peaking in the 1990s, our study suggests that the measures to restrict the amount of debris entering the Southern Ocean have been successful, at least in part. But more still needs to be done. By putting our data into oceanographic models we will learn more about the sources and sinks of plastic waste and how it is transported into and around the Southern Ocean."

In another study led by BAS, seabird ecologist Professor Richard Phillip looked at plastics eaten by three species of albatrosses on Bird Island, the black-browed albatrosses, the wandering albatross, and the giant petrel – all of which have a habit of eating indigestible items that they mistake for food.

The BAS-led team sorted the debris collected from the birds' nests by type, size, color, and origin and found that the plastics eaten by the birds weren't the same as those found in birds that live on South Georgia and surrounding islands. Instead, the wandering albatrosses and giant petrels were eating mainly food wrappers from South America, suggesting that the birds had eaten the debris by scavenging behind ships, picking up what had been tossed or washed overboard.

"Our study adds to a growing body of evidence that fishing and other vessels make a major contribution to plastic pollution," says Phillips. "It’s clear that marine plastics are a threat to seabirds and other wildlife and more needs to be done to improve waste-management practices and compliance monitoring both on land and on vessels in the South Atlantic.

"There is some good news, we found that black-browed albatrosses typically ingested relatively low levels of debris, suggesting that plastic pollution in the Antarctic waters where they feed remains relatively low."

The findings were published in Environment International.

Source: British Antarctic Survey