Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley have invented a material in powder form that adsorbs carbon dioxide with astonishing performance. Just 200 g (a little under 0.5 lb) can suck up 44 lb (20 kg) of CO2, the same as a tree does in a year.

It's called COF-999, which is short for Covalent Organic Frameworks. The term refers to a class of porous crystalline materials that have large pores, plenty of surface area, and low density. This makes them suitable for direct air capture (DAC), the process of sucking existing CO2 out of the air. Given the alarming levels of CO2 concentration in the atmosphere today, this is the sort of breakthrough the world needs.

How does COF-999 capture carbon from the air?

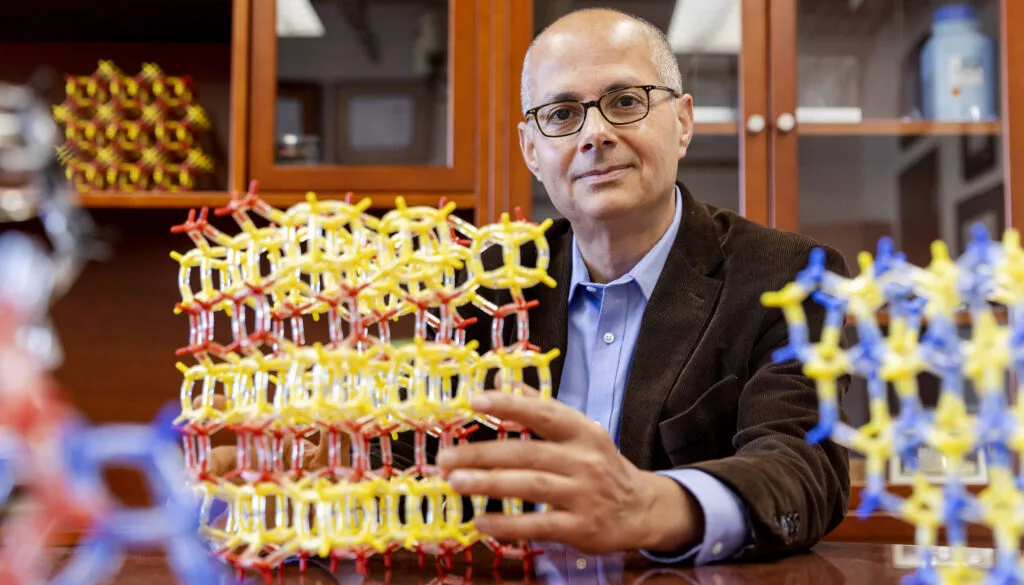

The material was developed by a team led by Omar Yaghi, a professor of chemistry at UC Berkeley and the inventor of COFs. He's been developing materials like this since the 1990s.

COF-999 has pores decorated with compounds called amines, which can grab onto CO2 molecules. Its porous structure allows for a large surface area to capture carbon, while its covalent bonds are incredibly strong. As ambient air passes through the powder, the basic amine polymers in COF-999 grab onto the acidic CO2, trapping it.

While DAC methods have previously used amine solutions in water, COF-999 is a better material for the job in many ways. For starters, you don't need to heat it up to make it work; it can capture CO2 at room temperature. It can also be reused at least 100 times without degrading or losing capacity, and it can selectively adsorb a large amount of CO2.

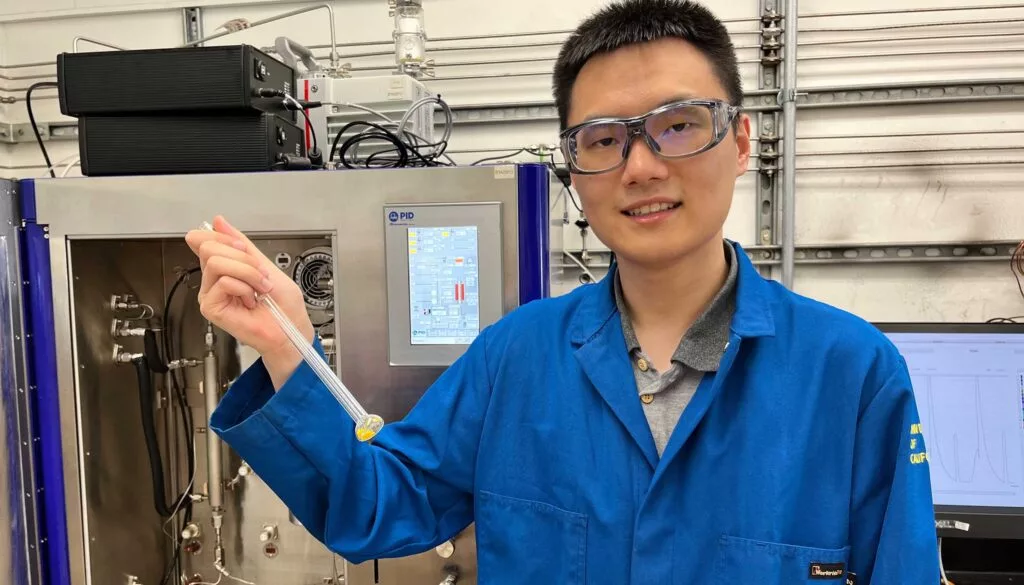

Plus, study leader Zihui Zhou told the LA Times that COF-999 captures carbon dioxide "at least 10 times faster" than other DAC materials.

Once the powder has captured CO2, it can be heated to 140 ºF (60 ºC) to release it. That CO2 can then be sequestered permanently in underground geological formations so it doesn't pollute the atmosphere, or used to produce materials like concrete and plastic.

Can we start cleaning up our air already?

DAC plants are already in place or in the works around the world, but they're expensive and energy-intensive to run. According to the World Economic Forum, it presently costs between $600 to $1,000 to remove 1 ton of CO2 from the air; the agency noted last year that this figure needed to fall to less than $200 for the technology to be widely adopted.

As for COF-999, it needs more testing and refinement before it goes mainstream, and according to Yaghi, that could take about two years. The material can be optimized to capture more CO2 and handle more capture cycles before degrading.

Yaghi also isn't clear on what COF-999 costs to produce just yet, so we don't know how much it'll contribute to lowering DAC costs. However, he noted that it doesn't require expensive materials to manufacture, so there's that.

According to the International Energy Agency, we're currently only capturing 0.01 megatons of CO2 annually across the world. That's a tiny fraction of the 85 megatons we need to remove annually by 2030. Meanwhile, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates we need to remove up to 10 billion tons of CO2 annually by 2050 to achieve net zero emissions.

There's clearly a lot of work to be done – and hopefully, we'll see more inventions like Yaghi's marvelous yellow powder in the near future. A paper on the study was recently published in the journal Nature.

Source: UC Berkeley