The idea of intervening in global warming by creating artificial clouds that are whiter and brighter, and therefore reflect more solar energy back into space and cool the planet, is one some scientists are giving plenty of consideration. A new study has shown how the world’s shipping routes are inadvertently serving up a live experiment, quantifying how the clouds seeded by pollution they create can block solar energy, and measuring the effect this could be having on global temperatures.

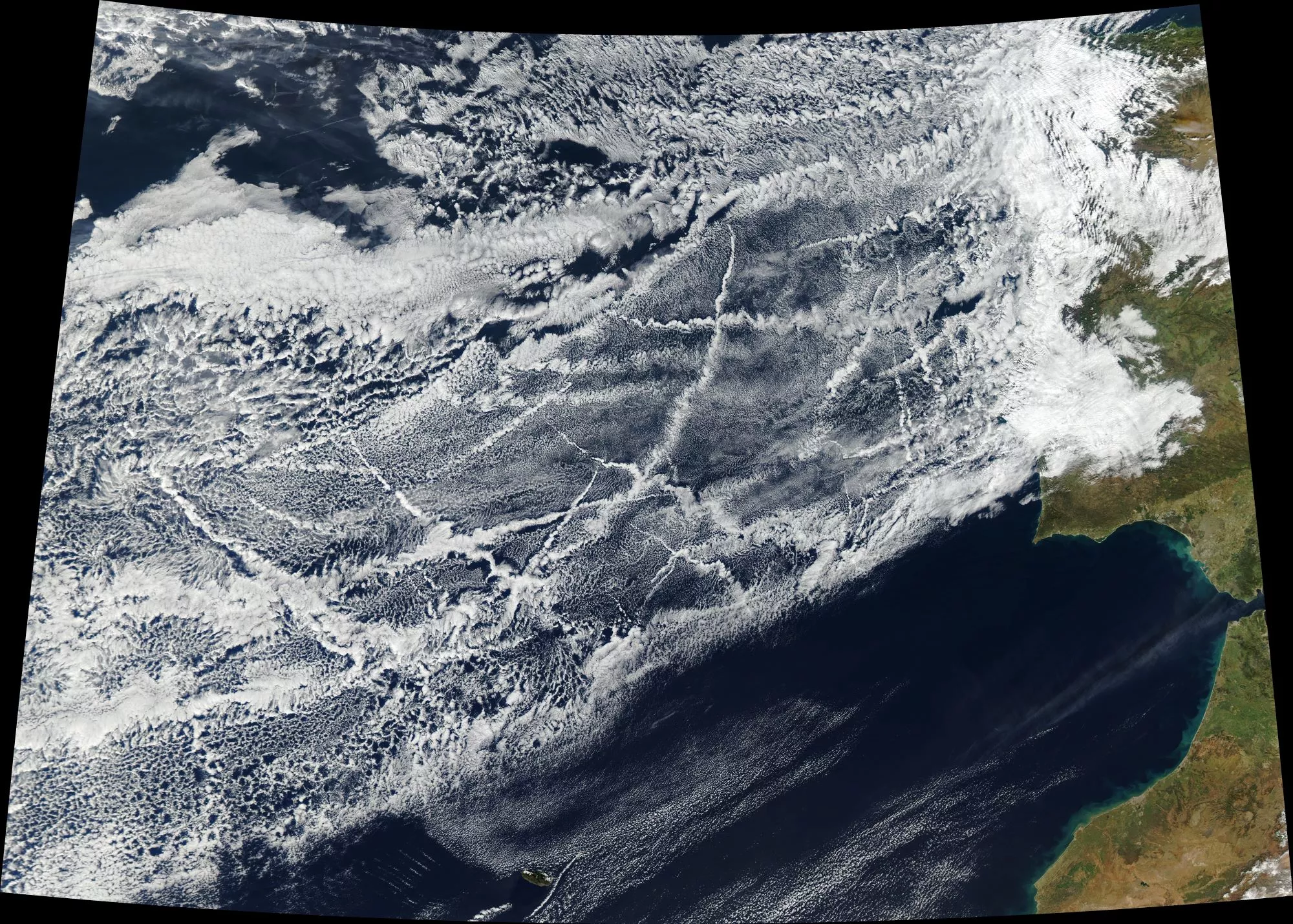

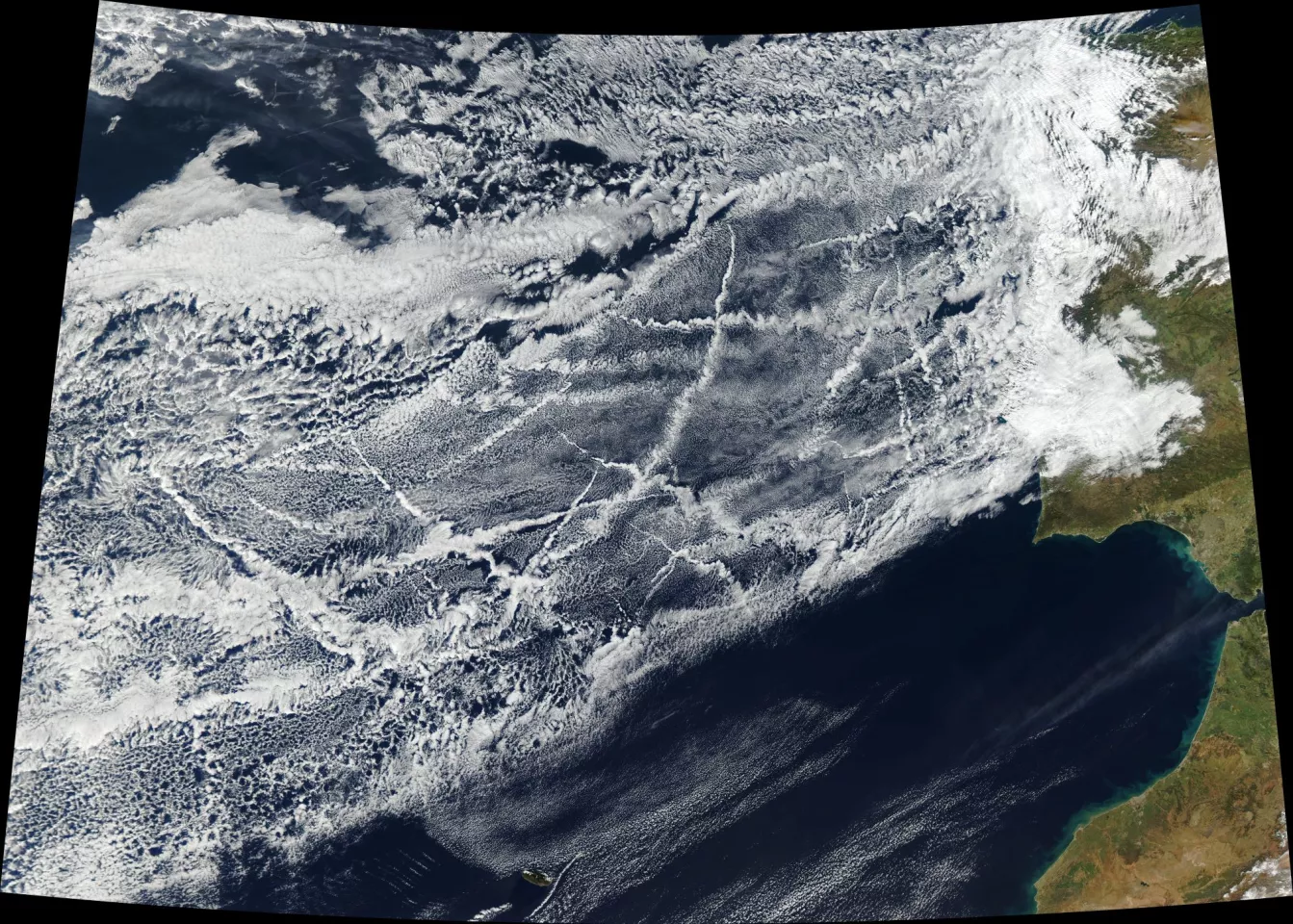

As cargo ships make their way around the world they emit sulfur particles (among other pollutants) that can act as a type of "seed." Water vapor in the air can condense on these particles to create water droplets, which band together to form bright, reflective clouds. The higher the concentration of particles like airborne sulfate, the higher the concentration of small droplets, and the higher and more reflective the clouds.

This phenomenon has been known about for years, with the clouds offering NASA and others ways of tracking shipping pollution, and while they were suspected to be impacting the climate, a new study from the University of Washington (UW) is claimed to be the first to measure these effects over a period of years.

“In climate models, if you simulate the world with sulfur emissions from shipping, and you simulate the world without these emissions, there is a sizable cooling effect from changes in the model clouds due to shipping,” says first author Michael Diamond, a UW doctoral student in atmospheric sciences. “But because there’s so much natural variability it’s been hard to see this effect in observations of the real world.”

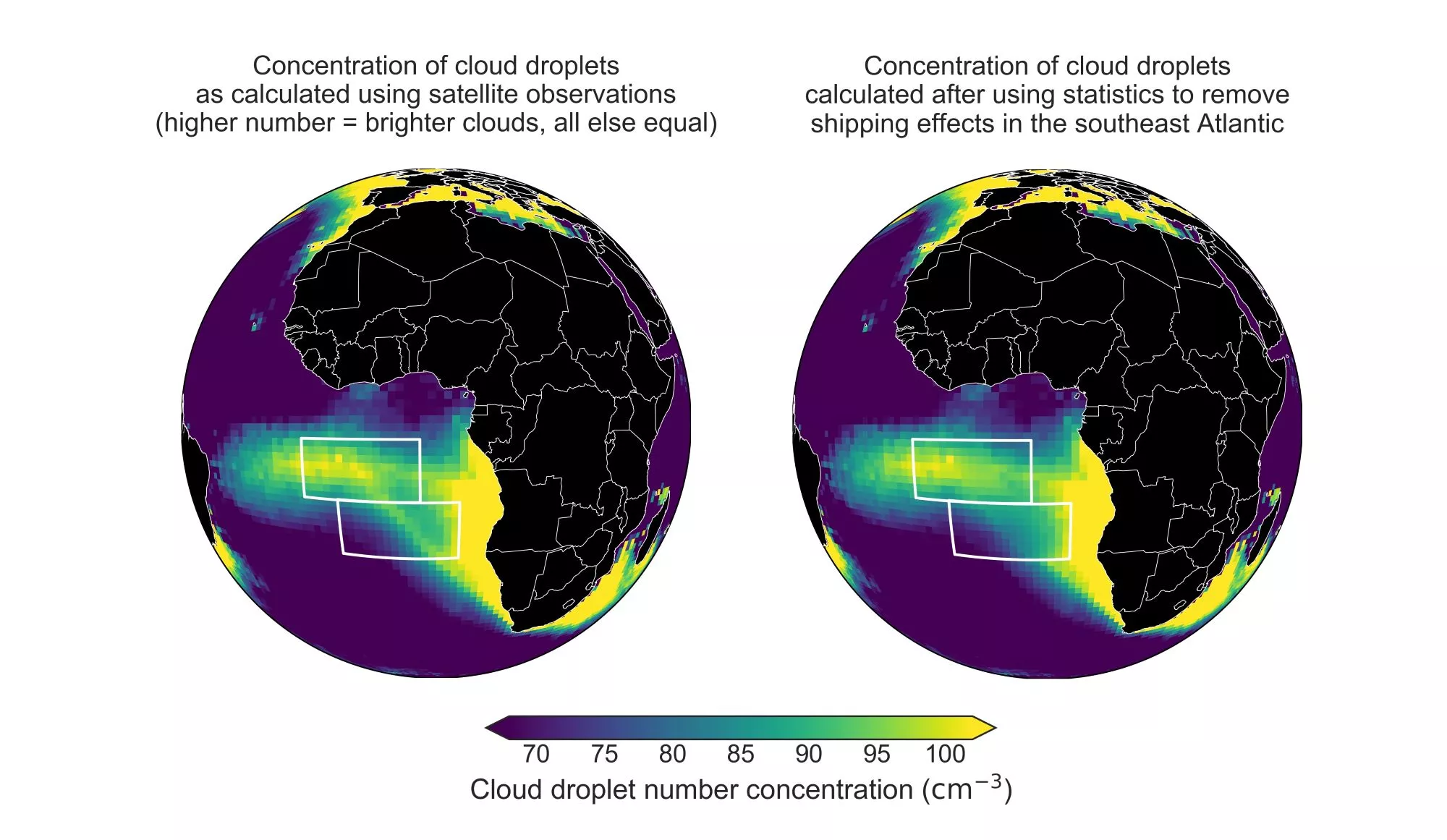

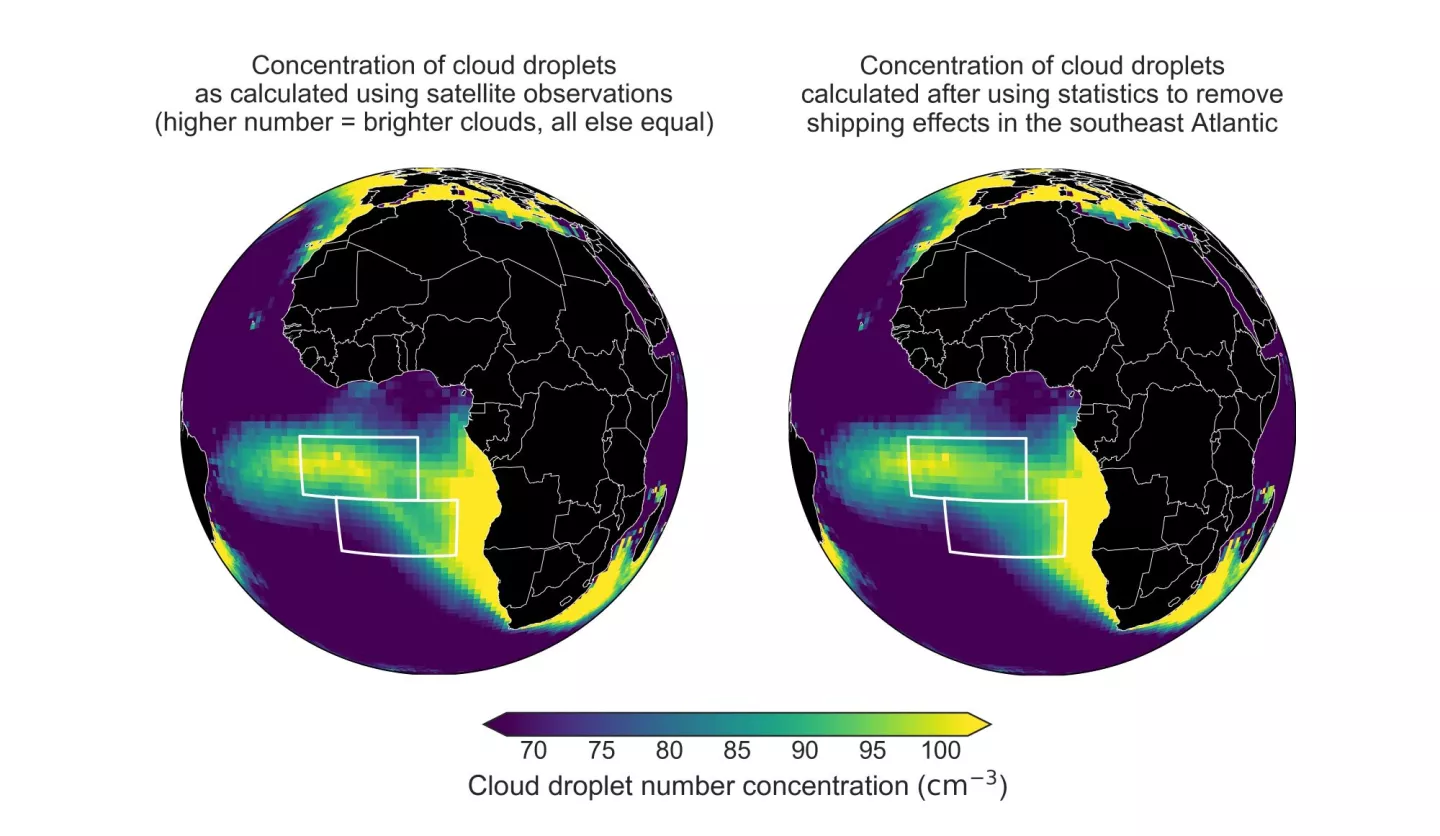

Through satellite data, the scientists looked at clouds emanating from the shipping route between Europe and South Africa, from 2003 to 2015. Their analysis looked at the clouds hanging over the shipping route, analyzing their properties as well as measuring the amount of reflected sunlight at the top of the atmosphere. These pollution-seeded clouds were compared with natural clouds from nearby unpolluted areas to ascertain the impact the pollution was having on their reflectivity.

“The difference inside the shipping lane is small enough that we need about six years of data to confirm that it is real,” says co-author Hannah Director, a UW doctoral student in statistics. “However, if this small change occurred worldwide, it would be enough to affect global temperatures.”

All up, the team estimated that the modified clouds over the shipping route block an additional 2 W of solar energy from hitting each square meter (10.7 sq ft) of the ocean surface in the vicinity of the shipping lane. As a way of exploring what this could mean on a global scale, the team applied their methods to calculate the impact of clouds modified by all forms of industrial pollution and estimated that they block 1 W of solar energy per square meter of the entire Earth's surface.

Taking this a couple of steps further, the team says that without the cooling effects of these pollution-modified clouds, the Earth could have already warmed by 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) since the late 1800s. The scientists are by no means arguing that pollution from shipping is a good thing when it comes to the global climate, only that the study serves as further evidence that cloud seeding could have some impact, though it would take a long time to quantity them.

“What this study doesn’t tell us at all is: Is marine cloud brightening a good idea?” says Diamond. “Should we do it? There’s a lot more research that needs to go into that, including from the social sciences and humanities. It does tell us that these effects are possible – and on a more cautionary note, that these effects might be difficult to confidently detect.”

The research was published in the journal AGU Advances.

Source: University of Washington