Polar ice and glaciers aren’t the only things at risk of melting as a result of climate change. The Arctic permafrost is beginning to thaw as well, with scientists concerned that this will release huge amounts of greenhouse gases stored there. But now researchers at Purdue University have found that methane-munching microbes might counter some of that, resulting in far lower emissions than previously thought.

In extremely cold regions around Siberia and the Arctic, the ground can freeze solid, locking away vast stores of carbon, methane, plant matter and microbes. And of course, as that permafrost begins to thaw out, those things are released again.

These emissions are already being recorded, with methane detected bubbling out of the ground and the East Siberian Sea at high levels. It may not get as much attention as carbon dioxide, however, methane is even more potent as a greenhouse gas.

But according to the new Purdue study, we may be overestimating just how much methane will end up in the atmosphere. That’s because of an often overlooked factor – microbes. Specifically, a group of bacteria called methanotrophs, which consume methane.

Methanotrophs live in organic-rich wetland soil in the Arctic, although this environment gives off far more methane than the bugs can consume. But the researchers on the new study discovered brand new species of methanotroph in Arctic mineral uplands. These soils are drier and contain far less methane, so the new species absorbs the gas from the air.

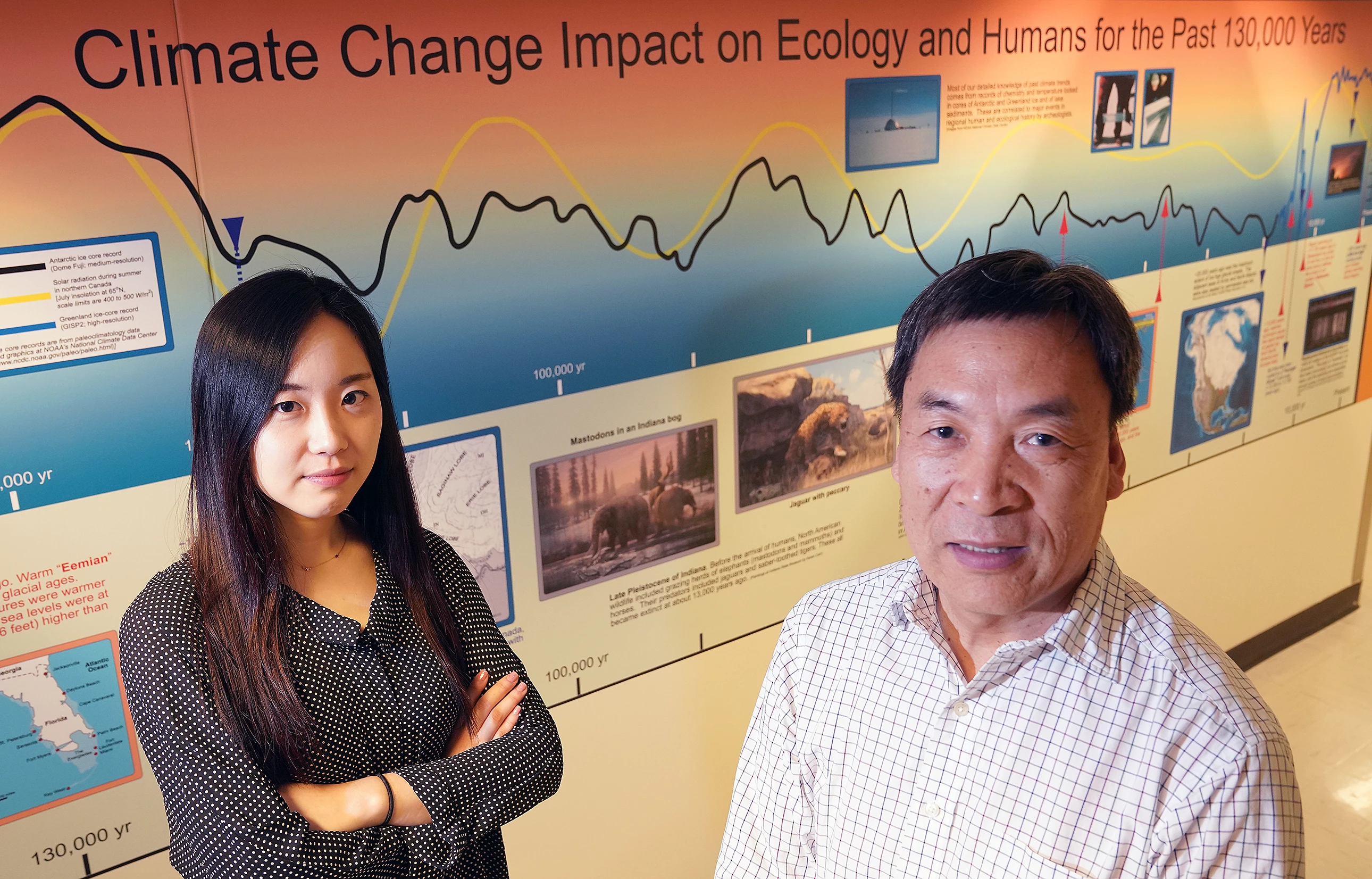

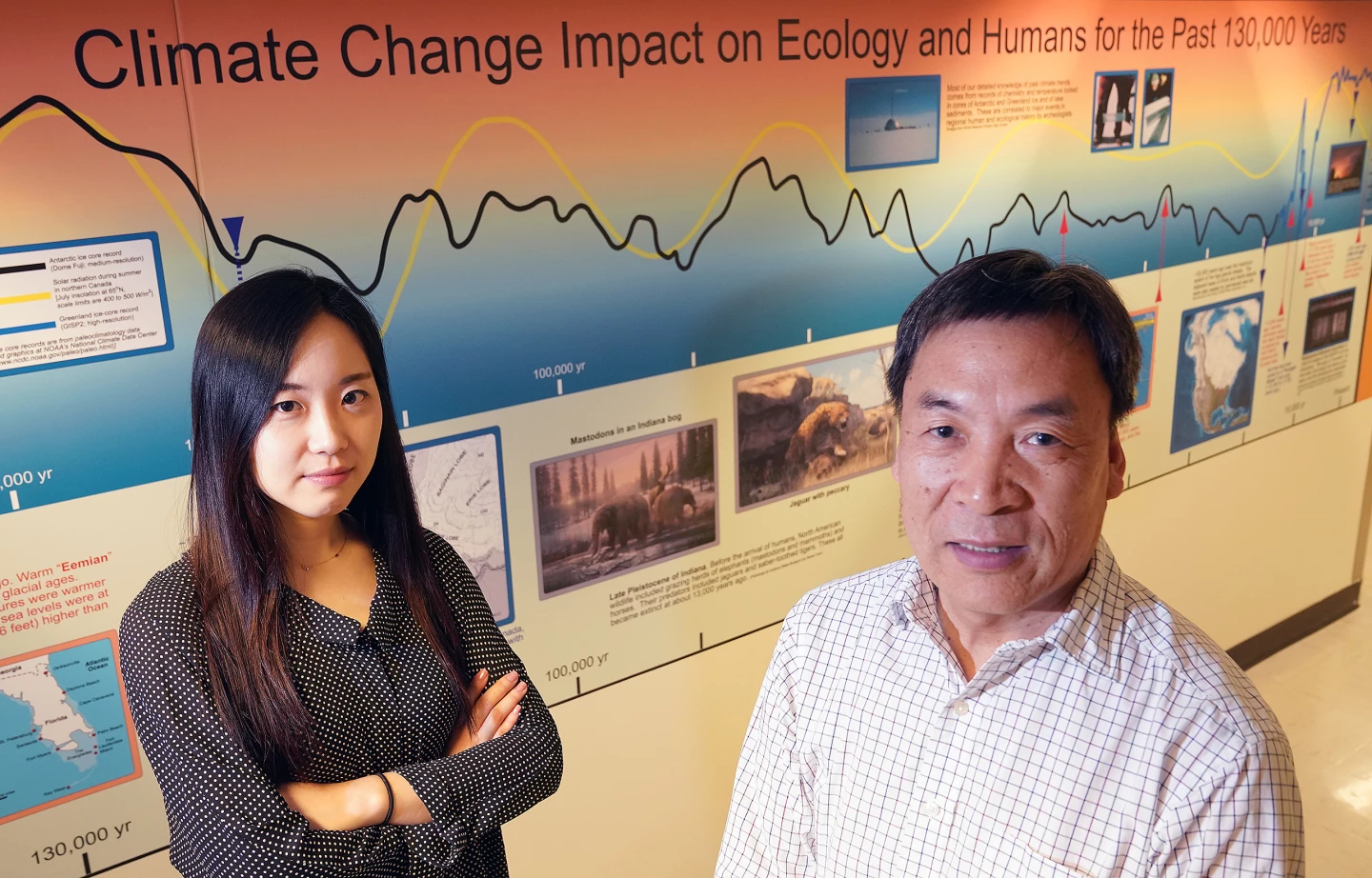

“This group of bacteria utilizes atmospheric methane as an energy source,” says Qianlai Zhuang, co-author of the study. “The emissions from wetlands will potentially be quite large, but if you consider the uplands, then the area-aggregated net emissions will be much smaller than previously thought.”

Realizing that these microbes hadn’t been included in prior calculations, the researchers then added their methane consumption into a biogeochemical model. And sure enough, the methane emission projections dropped. Interestingly, the team says that this falls in line with observed trends of methane emissions, which hadn’t been as quick to increase as had been predicted.

That said, the researchers are careful not to let their work inspire complacency for climate change. After all, it’s still a serious problem, and this doesn’t account for emissions in other parts of the world. Plus, the team says things could change as the temperatures heat up.

“We do believe that Arctic methane emissions will increase by the end of this century as other studies have shown, but the net increase to the atmosphere will be much smaller once upland methanotrophs are taken into consideration,” says Youmi Oh, co-author of the study. “It was even possible in our simulation that net emissions decrease because high-affinity methanotrophs survive better than methanogens in response to warming.”

The research was published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Source: Purdue University