Upper Story's second board game uses a gorgeous array of mechanical gadgets to give kids a physical, visual, fun way to understand electronics – and to give parents the feeling their young genius might be able to get them into a better nursing home.

It's one of these stealth education-type initiatives, a chance to plant concepts in young minds. In theory, a kid who's played Spintronics should have a head start when it comes time to play with real circuits, because they've had a chance to interact with some of the arcane, invisible concepts of the electronic world in a way that makes them much more tangible.

In this way, it's akin to the company's first game, Turing Tumble, which attempts a similar subterfuge using small marbles falling, all clickety-clackety like, through a grid of mechanical seesaws and gears to introduce kids to binary logic, switches and the fundamentals of computing. We tested the Turing Tumble last year, setting my then 8-year-old son Max loose on it, and it's a set he continues to bust out and fiddle with a year later.

This year, we have upgraded to a 9-year-old Max, and Upper Story has sent a fresh Spintronics: Act One set to throw before him. It's an immediate step up in aesthetics; where the Tumble was unapologetically simplistic and functional in design, the Spintronics set goes for an ornate, brassy and old-timey look. Steamlesspunk, you might call it.

You can clearly see the love that's gone into the components here, from the gramophone-style "ammeter," to the exposed planetary gearset in the "junction," to the spring-loaded "capacitor," to my personal favorite: the creamy-smooth, fluid-damped "resistors," which rotate in such a roundly satisfying manner that they could sell as fidget toys.

So how does it work? Well, Upper Story calls this "the first mechanical equivalent of electronics ever built," and I'm not in any position to argue. In the Spintronics universe, electrical energy is represented by kinetic energy, supplied by a "battery" – a spring-loaded pull-cord driving a column of gears. These gears are connected to the various components to form circuits, using a series of chains that more or less serve the function of wires.

Since the vast majority of the Spintronics experience involves building and deploying these chains, let's look a little closer. To be clear, the game doesn't ship with chains. It ships with a bag full of tiny 7 x 10 x 4 mm (0.3 x 0.4 x 0.2 inch) plastic chain links, with which the player must build chains of the appropriate length for each puzzle circuit.

It is hard to overstate the sheer fiddliness of these chain links, although if you read on, Max manages to turn it into a tale of endless woe. It's worst when you first start the game, and you're immediately asked to fiddle 40 or so of these links into your first chain to complete the first challenge. Each subsequent challenge tends to require further fiddling; you'll either be fiddling new chains into existence or fiddling previous chains into new lengths to suit the circuit you're making.

As a parent, I'm OK with this, as it aligns with my broader goal of training Max up into a highly-paid genius who can provide me in my later years with a grade of lavish lifestyle typically unavailable to emerging technology writers. Working these links into shape requires a neurosurgeon's patience and precision, and if he's not to become a computing or electronics-based billionaire, I'd be happy enough to settle for a neurosurgeon. Shoot for the Moon, land among the stars, that sort of thing.

Max, on the other hand, is less impressed. "I hate the chains," he enthused. "Hate, hate, hate. It takes so much effort just to build the starting circuit! And say I build one circuit, but I need to build another one. The pieces have to go in different places to do it, so you have to make new chains every time. If this chain isn't the right length, I might scream. Why does my Ribeena taste like blood? "

"If I have to build a really big circuit," he continued, "with a bunch of junctions and pieces requiring a lot of different lengths of chains, I wish I was in a cartoon, so I could say 'CHAIN BUILDING MONTAGE' and put on Merry Go by Kevin McLeod, and skip the chain pain. Seriously, this tastes like blood."

I'm disturbed to confirm the Ribeena does indeed taste a bit like blood. I don't know what to do about that, so let's move forward, and get Max to describe Spintronics in detail from a young player's perspective. Buckle up, because like his dad, he's a man of many words.

"Spintronics is a puzzle game that uses pieces with different functions to make different circuits," he said. "It's sort of like how Turing Tumble works. Damn, I found a hole in my disco ball balloon. All these pieces work kind of like cogs, connected to different parts of a mechanical machine with different functionalities. The chains... Work like chains, except I hate them.

"You know bicycle chains? I like those. They're fun to fiddle with for me. But Spintronics chains? They're just complete hell. Especially when I use up all my pre-made pieces of chain, and I have to make a new one from scratch with the tiny little chain links. Absolute hell I tell you, pure hell.

"When you pull the string, the battery moves all the various pieces that are connected to it. To build circuits, you need some simple mechanics. Pieces connected to the battery, which powers the circuit. Two, you need to have those pieces connected to other pieces. Three, you need an objective for what you're supposed to build. If you follow the puzzle book and don't just free-build, there's usually an objective. Let me find a good one.

"Say puzzle 23, it's called the pitch switch. It requires an ammeter, a piece that makes sound based on how much it spins, and you need to build a circuit where the ammeter makes a higher pitched sound when the switch is on than when it's off. If it sounds complicated, well, understanding what it means is easy when you know all the pieces well.

"But building the circuit is pure hell. I've already told you about the chains, but in the trial and error of building the circuit, every error requires more chains. Which I hate. You can kind of drag the pieces around to make different lengths fit sometimes, but not always.

"What have I learned? OK, resistors kind of slow down the circuit, they're used in most of the circuits. But another thing you probably weren't expecting me to say, because it's kind of weird and off track, is that... What's this thing called again? Ah, the resistors contain silicone oil. It seems weird and random, but they do. It helps with the resistance, apparently.

"The components get more interesting as you go on. I think the most interesting are the ammeter, the capacitor and the junction. I've already talked about the ammeter, but it also looks like a giant gramophone. That's those horn-on-a-box things that old people used to listen to music. I think they made a lot of static.

"The junction, apparently, is like a pipe junction. All the energy goes into it, some of the energy comes out one side and the rest comes out the other. Also if you look at it sideways, it looks like a pine tree. Actually, spruce, let's say spruce.

"And the capacitor, apparently it's like a battery, it can be charged by the battery. I haven't got up to many capacitor circuits yet, but it's sort of springy. I'm guessing you have to charge it up to a certain point, and then release it.

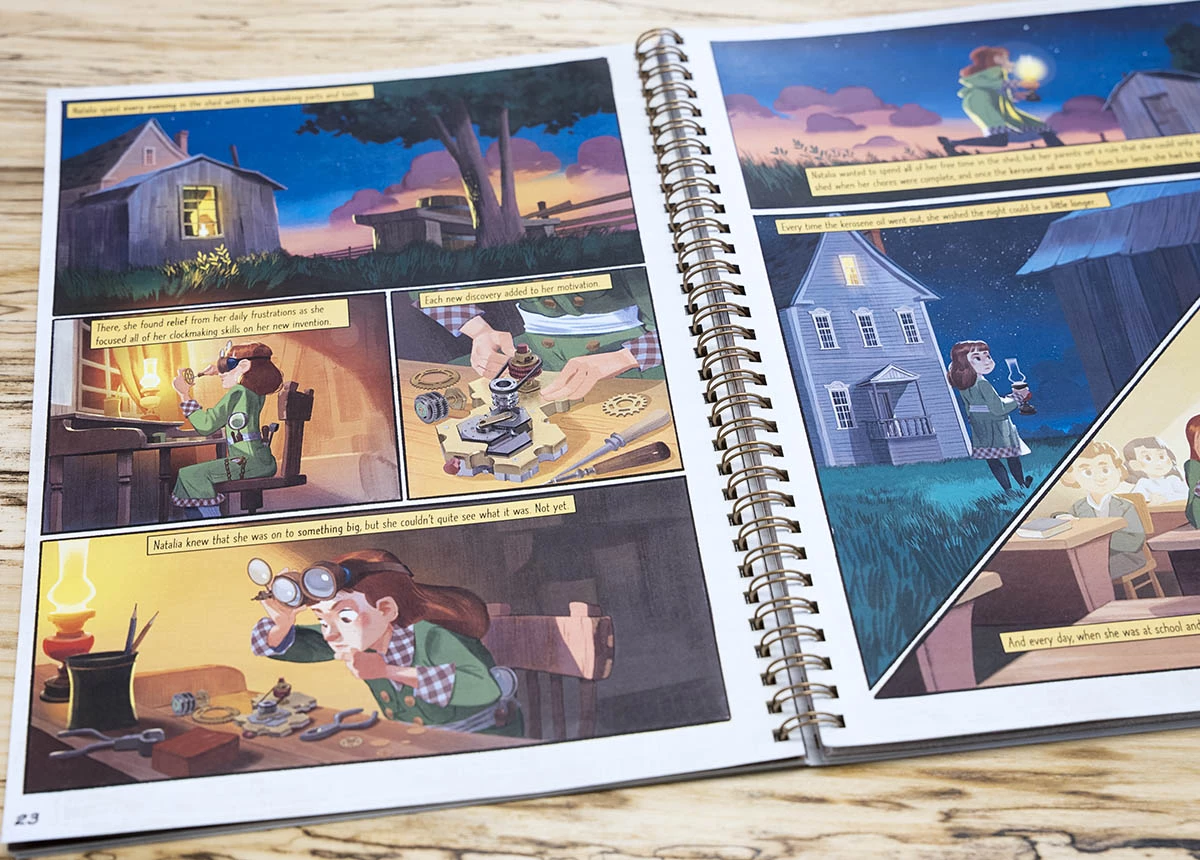

"The story is about a girl named Natalia, whose family made different kinds of clocks. Her mother made clocks with great accuracy, and her father made clocks that were more beautiful. Natalia loves making clocks too, but eventually, other people realized they could make clocks in their town.

"They weren't beautiful or accurate, but they were cheap to make, so people bought them. So the family had to go on the road to find somewhere else. And they found a place, it looks kind of wild-westy, and it's called Little Hope. It seems that's some sort of joke. And Natalia goes to a storage room and starts clockmaking. All the puzzles are supposed to be what Natalia's doing down over there. That's all I'm saying, I'm not gonna spoil it for anyone.

"Spintronics is kinda fun. It's challenging. You can get pretty raged-up when you're playing it, because it gets pretty challenging. But it's still doable. So yeah. I like the feel and the look of the parts. And I like building my own circuits that aren't in the book, but there's a bit more error than trial in that. Usually the circuit doesn't do much."

And so to the crucial question: has it made Max a bankable electronics genius? "Maybe," he pondered. "I can't say exactly. You can't say it's fully electronic. But maybe I could somehow miraculously make some not-wasting-electricity, not-harming-the-environment cog machines, or something like that. Or maybe my head might explode because of chain rage. But if you want me to become an electronics genius and pay for a bunch of stuff you guys can't afford, that'll probably take a while. And a lot of miracles. Ooh, you've put the double pedal on the drums. When I hum into the snare drum, it sounds like static."

Any final thoughts, buggerlugs? "I want to say to the Spintronics people that I'm sorry we took so long to write this article," he said. "What's the company called again? Upper Story? We had a lot of other things that we needed to do, or something. And it's weird, because dad could've just dragged me into his office and worked on this. But he doesn't work on the weekends when I'm home, of course, and today I'm home from school because my eye just went crazy and got super itchy. So yeah. Now we got the review done! Also one of the reasons it might've taken so long is because I was fiddling with the ammeter and I broke it, and we needed a new one. So thanks for that!"

"Probably the final note," he concluded, "is that whenever I'm packing the Spintronics set up, I always have a fear that there's bits of chain left on the ground when I'm done, which might rattle up the vacuum tube, as dad likes to say. That's another bad thing about chains."

At this point, my finely honed sense of fatherly intuition is telling me that he's not particularly keen on the chains – or at least, that he's finding great joy and humor in complaining about them, which is somewhat of a tradition in our family and a grain of salt to be taken with this review. But he does seem to enjoy getting the challenges done, and then explaining his circuits in great detail to his five-year-old sister, who stands there listening politely until he's finished speaking, and then typically says something like "I'm a skeleton fairy princess of death, and I ride a ghost unicorn."

So chains or no chains, it does seem to be engaging enough to keep him going, and while some prodding has been required, I don't get the sense that it feels like homework. He's always a sucker for a comic book story, and he's starting to get his head around some interesting concepts.

The components themselves are beautifully built, mechanically fascinating, and they become even more cool and complex in Spintronics: Act Two, an add-on game which introduces an "inductor" that swings weighted balls back and forth like a proud newlywed exiting the shower, and a "transistor" that introduces the concept of a voltage-controlled resistor.

The price of entry here is not cheap. You're looking at US$75.95 for Spintronics: Act One, or US$139.95 if you bundle it up with Act Two. On the other hand, you can easily burn that kind of dough furnishing your tyke with video games, and Spintronics is a real thing.

It is also a virtual thing, as it turns out. Max's face lights up with sheer glee when he discovers that Upper Story has released a free, online Spintronics simulator that can be built and operated on-screen, including the full array of components, in which chains can be added and removed with a couple of clicks. An electronic emulation of a mechanical emulation of electronics.

It's probably best to hide this simulator from the young'uns in your life; it'll make little sense without the game booklet, it'll do little on its own to demystify the weird ways of the electron, and as most parents will agree, the last thing these savages need is another excuse to use a screen. But it's a neat little Easter egg for people who've enjoyed the physical game set and who want to steam through the challenges a little quicker.

As with the Turing Tumble, Upper Story has taken a complex set of concepts and cleverly wrapped them up into a comic book and physical board game that's proven compelling and educational to 100% of the children we've tested it on. It's clear these guys build things with love, and from the pretty box to the detailed parts, it's at the very least a sweet thing to have in the house.

We'll leave you with Max talking you through a circuit – the final challenge in the book, because he thought that'd look the coolest, even though he's not up to half way through yet. Apologies in advance: vertical video.

Source: Upper Story