Although robotic prosthetic legs do have some advantages over their conventional counterparts, they also have some drawbacks that keep them from entering wider use. A new prototype prosthesis, however, addresses some of those shortcomings.

When utilizing a regular non-robotic prosthetic leg, users typically have to lift and swing their hip with each step, in order to lift the leg off the ground and move it forward. This results in an unnatural gait that is not only tiring, but may also lead to pain and injuries over time.

By contrast, robotic legs contain motorized joints that automatically bend the leg up and move it forward with each step. In order to fit into the limited space available, the motors are usually small and fast-spinning. A series of gears are used to deliver torque from those motors to the joints.

Unfortunately, though, all those spinning gears create a lot of noise, plus they add resistance that keeps the joints from swinging freely. Additionally, the motors use a lot of battery power, limiting the distance that the user can walk in one day.

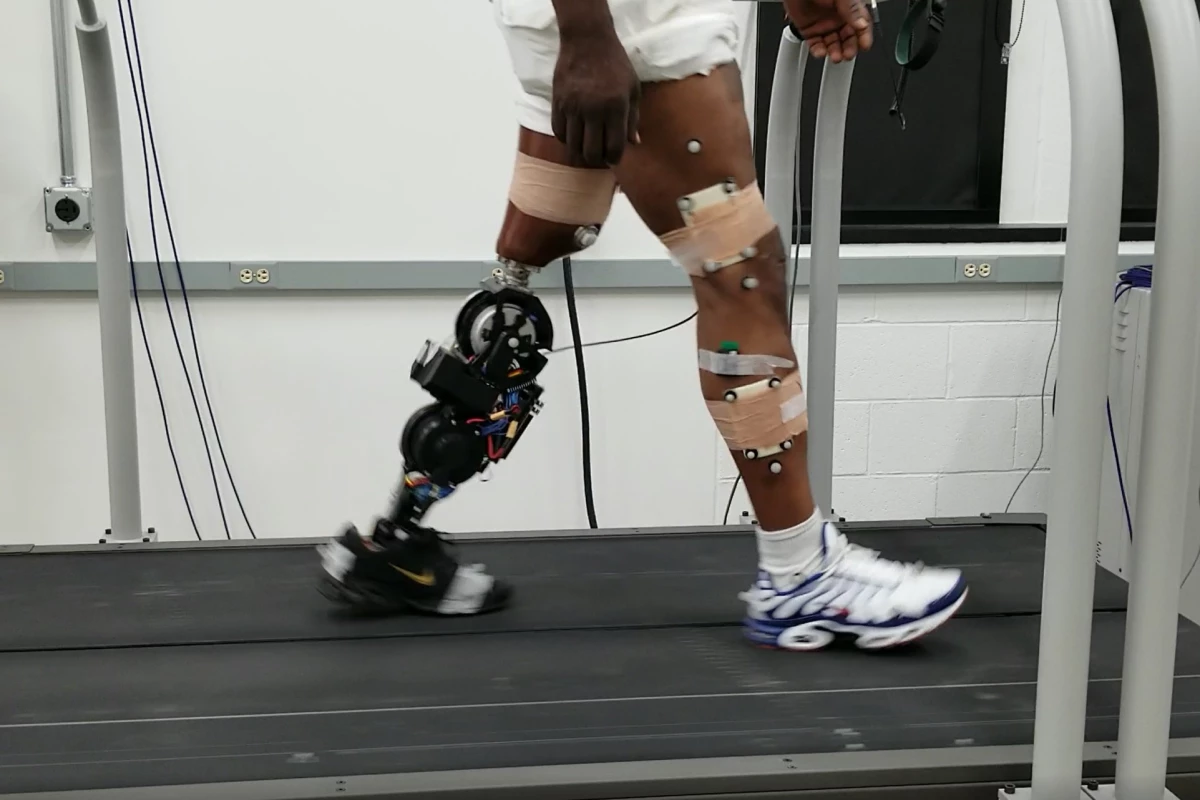

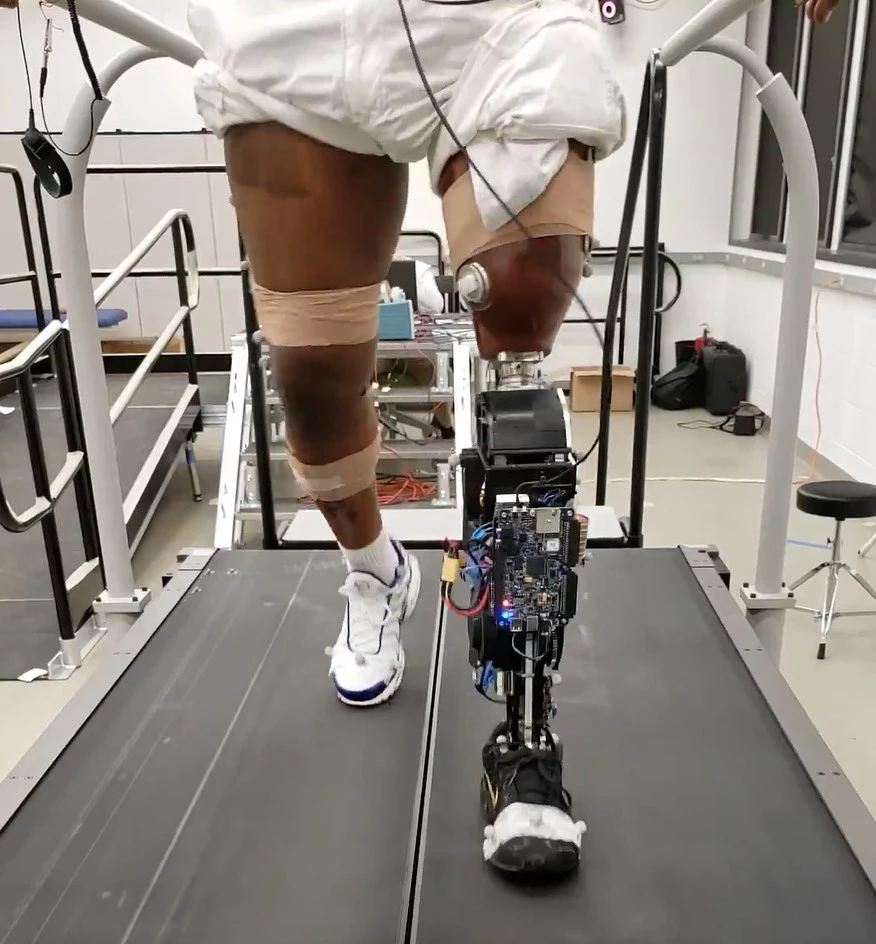

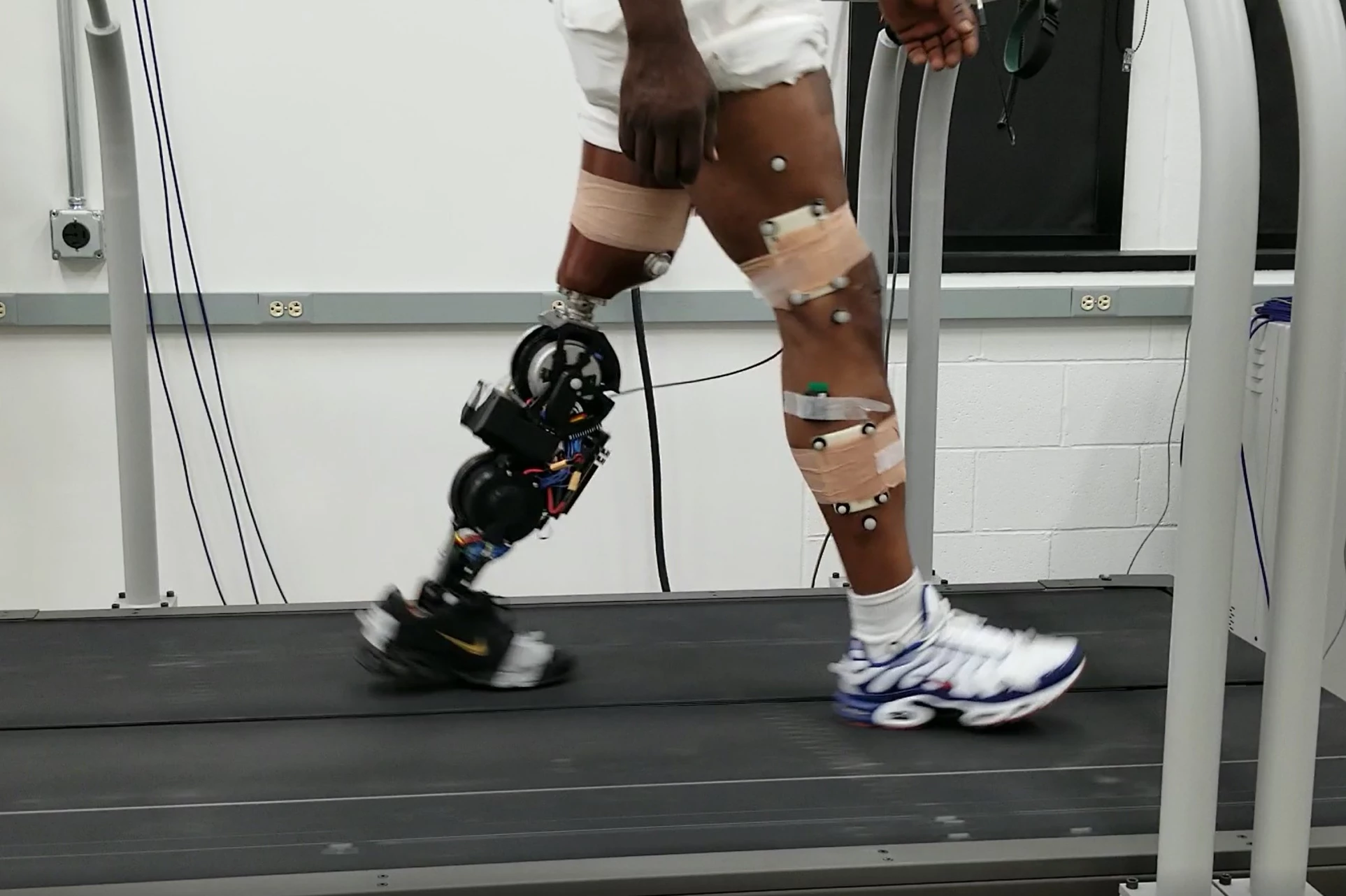

Seeking an alternative, scientists from the University of Texas at Dallas developed a prototype leg that utilizes motors which were originally designed for a robotic cargo-lifting arm on the International Space Station. Located in the knee and ankle joints, the two motors are powerful enough that only minimal gearing is required – this means that the leg is quieter than other robotic prostheses, plus it swings more freely.

Additionally, the robotic leg incorporates a regenerative braking system that slows it down at the end of each stride. This setup not only keeps the foot from meeting the ground with a jarring force, but it also charges the battery with the energy that is captured. As a result, it is claimed that just one initial charge of the battery is sufficient for an entire day's worth of walking – this is reportedly twice the range of other robotic prosthetic legs.

The scientists are now improving the control algorithms, so that the device will be able to automatically adjust to changes in terrain, walking pace, and activity. It can be seen in use, in the video below.

A paper on the research, which was led by Assoc. Prof. Robert Gregg (who is now based out of the University of Michigan), was recently published in the journal IEEE Transactions on Robotics.

Source: University of Michigan