A new study has discovered the reason why men tend to sustain more heart muscle damage following a heart attack than women: the hormone testosterone. The researchers have also discovered a potential fix in the form of an existing drug.

In their World Heart Report 2023, the World Heart Federation noted that, for decades, heart conditions have been the leading cause of death globally, and the numbers keep rising. In high-income countries in 2019, the WHF reported, age-standardized death rates from cardiovascular disease were higher in males than females.

While previous studies have observed that men tend to have larger, more damaging heart attacks than women, the mechanism has remained unclear. Now, new research led by the University of Gothenburg in Sweden has discovered that when it comes to the damage caused by a heart attack, the hormone testosterone drives this sex-specific difference.

“We see that testosterone strengthens the inflammatory response in male mice, leading to more extensive heart injury,” said Åsa Tivesten, professor of medicine at the University’s Sahlgrenska Academy, senior physician at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, and the study’s corresponding author. “Testosterone plays a clear role in making inflammation worse following a heart attack.”

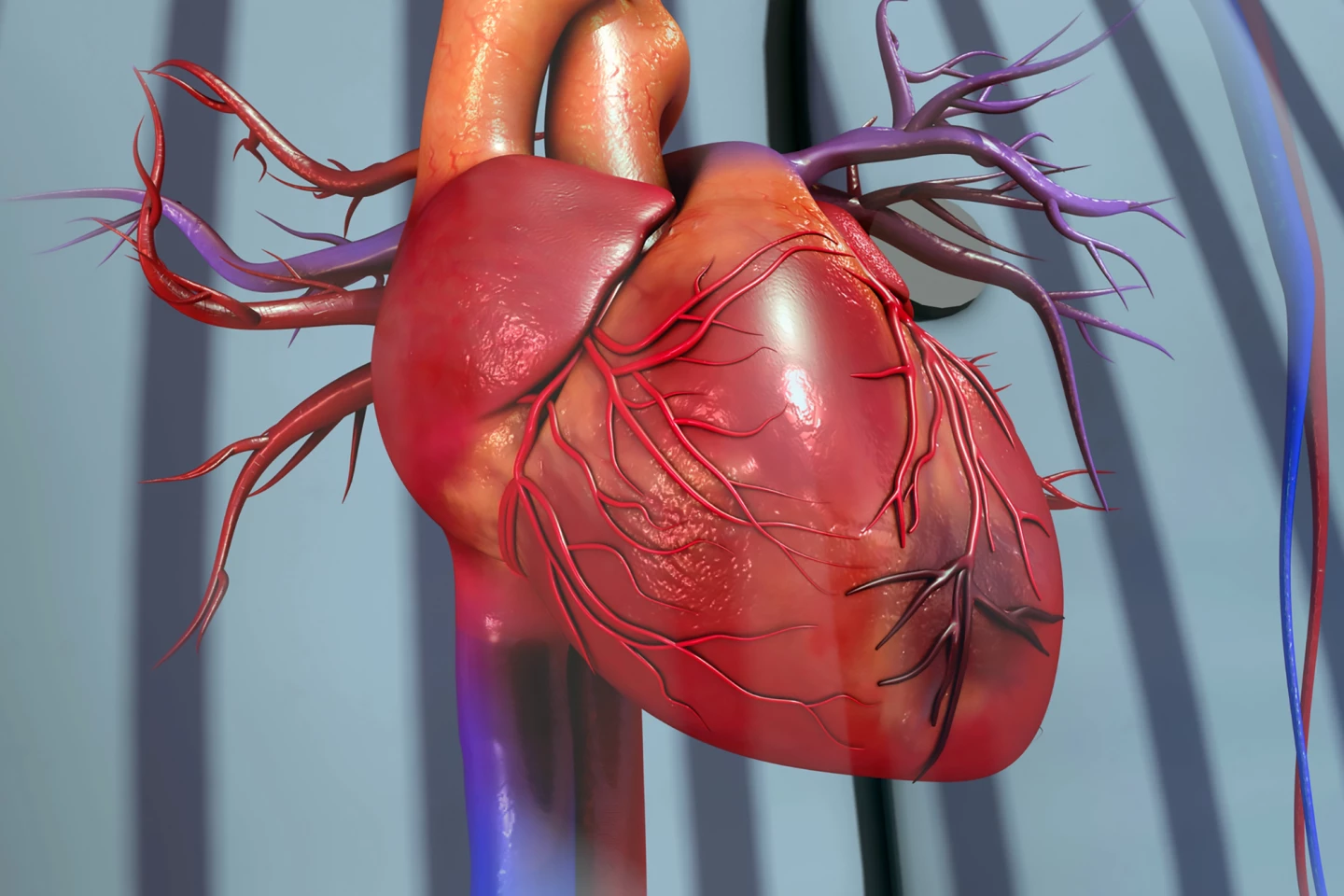

The most common cause of a heart attack – the medical term is myocardial infarction (MI) – is a blocked coronary artery. The blockage cuts off oxygen-rich blood to an area of heart muscle, causing the affected muscle cells to die within minutes. Neutrophils, front-line white blood cells, are rapidly released from the bone marrow in large numbers and recruited to the area, initiating an inflammatory response to clear up dead cell debris. The body’s response in the first few days after an MI determines the amount of muscle damage sustained and, consequently, how well a person will recover.

To better understand how the sexes responded to a heart attack, the researchers blocked a coronary artery in male and female mice for 45 minutes to induce an acute MI before returning blood flow to the damaged area (reperfusion) to trigger the inflammatory response. At 24 hours, the male mice had a higher number of neutrophils in the blood than the females, and they had larger areas of infarct or heart muscle damage. Additionally, at the 24-hour mark, testosterone levels were 15-fold higher in male mice than in females. In humans, male testosterone levels are normally more than 10-fold higher than female levels.

To confirm the effect of testosterone on post-MI neutrophil levels, the researchers compared castrated male mice with un-castrated ones. As expected, the castrated mice had reduced testosterone levels following an MI; however, at 24 hours, their blood neutrophil levels were similar to those of post-MI female mice. The infarct size was also smaller in castrated male mice. When the castrated mice were given a dose of testosterone, blood levels of the cardiac injury marker troponin I were higher than those of castrated mice who weren’t given a testosterone dose. Troponin I is a protein that escapes from heart muscle cells when they’re damaged and is routinely used to determine the severity of an MI in humans.

Searching for a way of dampening this testosterone-driven inflammatory response, the researchers looked at the data from a clinical trial where tocilizumab, an existing rheumatoid arthritis drug, was given to patients having their first acute MI. Tocilizumab belongs to a class of drugs called biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or bDMARDs. It blocks receptors for interleukin-6 (IL-6), a signaling protein that tells the immune system to become active after, for example, a heart attack, which dampens the body’s inflammatory response. The researchers found that giving tocilizumab before reperfusion reduced blood neutrophil levels and MI size more markedly in men than in women.

“Our study shows how testosterone affects neutrophils through a mechanism that was previously unknown,” Tivesten said. “These results illustrate the importance of considering sex differences in both research and healthcare. If these differences are overlooked, treatments may be less effective, especially for women, who are often underrepresented in studies.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: University of Gothenburg