While gray hair has been increasingly embraced in recent years, it remains a very visible sign of aging that some would prefer not to broadcast. And despite a lot of research into the mechanism that causes melanin-producing stem cells to run out of steam (and therefore the color pigment protein), it's still somewhat of a, er, gray area.

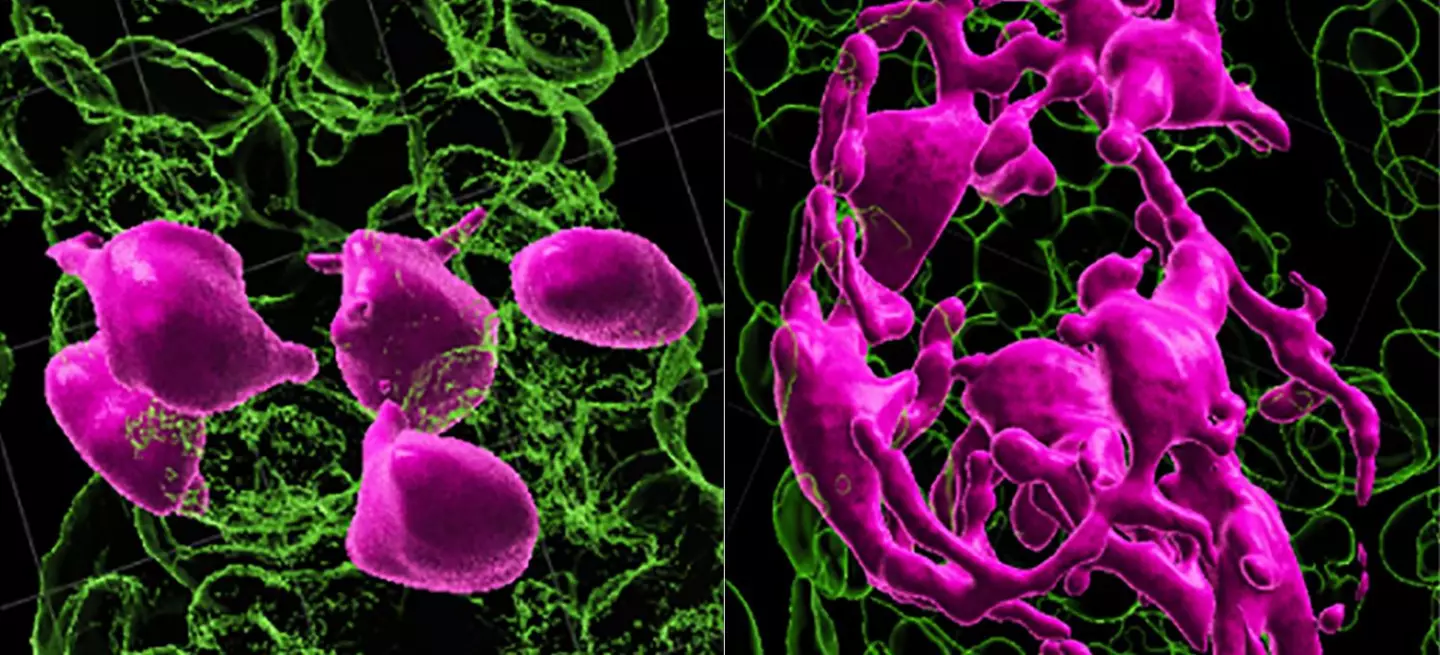

A breakthrough could be around the corner, with researchers led by a team from NYU Grossman School of Medicine studying these melanocyte stem cells (McSCs) in mice, which humans also possess. They found that the movement of these cells along the hair follicle is key to their transformation and, in turn, their pigmentation. Over time, the system breaks down and they become ‘stuck’ in one spot, unable to evolve into the type of cell that can be coaxed into producing color.

“It is the loss of chameleon-like function in melanocyte stem cells that may be responsible for graying and loss of hair color,” said study senior investigator Mayumi Ito, a professor in the Ronald O. Perelman Department of Dermatology and the Department of Cell Biology at NYU Langone Health.

McSCs show great plasticity as they age and move between different compartments of the developing hair follicle, which expose the McSCs to varying levels of maturity-influencing protein signals.

But as hair ages, sheds and grows back, MCSC numbers swell and they get ‘stuck’ in a compartment called the hair follicle bulge, which prevents them from moving back to their original position – the germ compartment – where WNT proteins would help them develop into pigment cells.

“Our study adds to our basic understanding of how melanocyte stem cells work to color hair,” said study lead investigator Qi Sun, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at NYU Langone Health. “The newfound mechanisms raise the possibility that the same fixed-positioning of melanocyte stem cells may exist in humans. If so, it presents a potential pathway for reversing or preventing the graying of human hair by helping jammed cells to move again between developing hair follicle compartments.”

Earlier, researchers linked WNT signaling and its stimulation of mature McSCs to produce pigment. The stem cells ‘stuck’ in the follicle bulge compartment, located directly above the germ compartment, were shown to be many trillions of times less exposed to the WNT signaling.

To demonstrate the hair growth-shed-regrowth cycle, the researchers plucked and forced the regrowth of hair in mice. What they found was that the McSCs packed into the follicle bulge increased from 15% to nearly 50% with the forced aging cycle. The cells were then unable to regenerate or mature into pigment producers. Meanwhile, the cells that moved between compartments carried on maturing and producing pigment over the length of the two-year study.

While the findings in mice models don't yet offer a quick fix for age-related graying, it does pave the way for research into the movement of McSCs in order to stop, or even reverse, the process.

“These findings suggest that melanocyte stem cell motility and reversible differentiation are key to keeping hair healthy and colored,” said Ito, a professor in the Department of Cell Biology at NYU Langone.

Researchers now aim to test how best to get the McSCs moving back to their germ compartment in order to produce pigment once more.

The study was published in the journal Nature.

Source: NYU Grossman School of Medicine