Eating just one extra serving of leafy greens a day could help protect your heart, according to a new long-term study that found that a higher intake of vitamin K1, found in spinach, kale and broccoli, was linked to a lower risk of dying from heart disease.

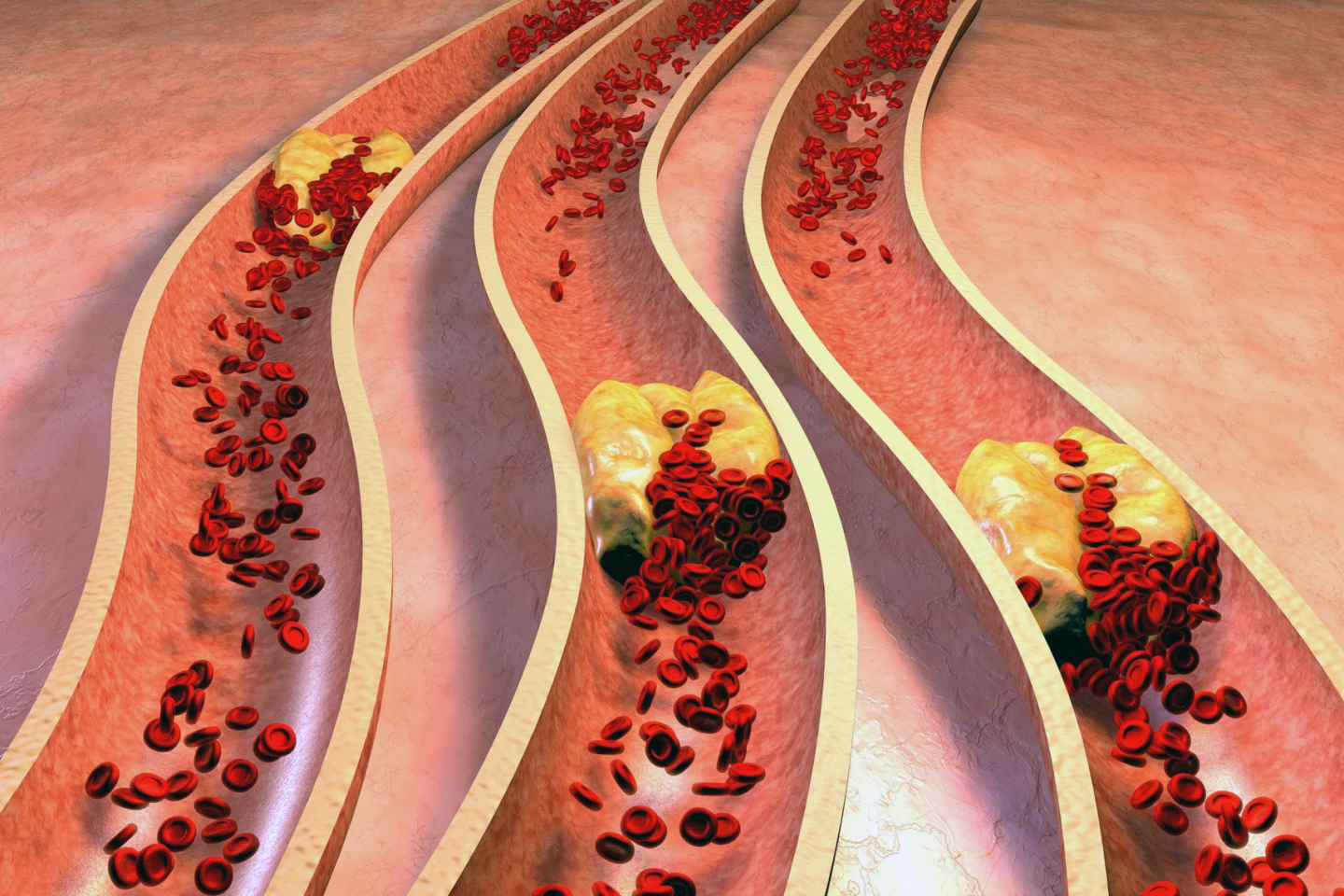

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), a group of disorders of the heart and blood vessels, are the leading cause of death globally. A subset of CVDs, called atherosclerotic vascular disease (ASVD), in which plaque builds up inside arteries, narrowing them and restricting blood flow, is the top cause of death because it often leads to heart attacks and strokes, the most deadly forms of CVD.

A new study by Edith Cowan University (ECU), the University of Western Australia, and the Danish Cancer Institute has found a simple way to reduce the risk posed by ASVD: boost levels of vitamin K1 by eating more leafy greens and cruciferous vegetables.

“Leafy green and cruciferous vegetables, like spinach, kale, and broccoli, contain vitamin K1 which may assist in preventing vascular calcification processes that characterize cardiovascular disease,” said ECU PhD student and the study’s lead author, Montana Dupuy. “The great news is that these vegetables can be easily incorporated into your daily meals.”

The researchers investigated whether eating more vitamin K1 was linked to better heart and blood vessel health in older women. Older women were chosen because they have a unique risk for ASVD, particularly stroke. The researchers looked specifically at subclinical atherosclerosis, early-stage artery thickening, and major heart and vascular problems over time, such as heart attacks, strokes, hospitalizations, or deaths due to ASVD. They recruited 1,436 Australian women with an average age of 75 and followed them for 14.5 years, using hospital and death records to track their progress. Participants’ vitamin K1 intake was assessed at the start using a food questionnaire.

Women who ate more vitamin K1 were found to have thinner carotid artery walls, which is a good sign because it indicates less early-stage atherosclerosis. Over 14.5 years, women with the highest K1 intake (around 119 µg/day) had a 43% lower risk of dying from ASVD compared to those with the lowest intake (which was around 49 µg/day). Heart disease and stroke deaths were also significantly lower in women with higher K1 intake. While there was a trend towards fewer hospitalizations for ASVD in women with higher K1 intakes, it wasn’t statistically significant.

“This research found women who consumed approximately 30% higher intakes of vitamin K1 than currently recommended in the Australian Dietary Guidelines had [a] lower long-term risk of ASVD,” said Dr Marc Sim, a Senior Research Fellow in ECU’s School of Medical and Health Sciences and corresponding author of the study.

The recommended daily intake of vitamin K1 in the US is 120 µg for adult males and 90 µg for adult females. In Australia and New Zealand, the recommended daily intake is 70 µg for adult males and 60µg for adult females. It's worth noting what and just how much you need to eat to reach 120 µg/day of vitamin K1. A cup of raw kale provides 472 µg, and a cup of raw spinach provides 145 µg. A half-cup of cooked broccoli will give 110 µg, and a half-cup of cooked Brussels sprouts 109 µg. Half a cup of cooked cabbage yields 82 µg of vitamin K1. So, in short, you don’t have to try too hard to achieve the goal of eating 120 µg a day.

The study is observational, so it can’t prove cause-and-effect; it can only show an association. Further limitations are that participants’ food intake was self-reported, which can be affected by memory or underreporting, only vitamin K1 was assessed, even though K2 may also affect heart health. Additionally, the study included older, mostly Caucasian Australian women, so findings may not apply to men, younger people, or other ethnicities.

However, the study has practical implications. Eating one extra serving – about half to one cup – of leafy green or cruciferous vegetables is unlikely to cause harm to most people, and it could significantly improve heart health. If you’re concerned, you should check with your physician before changing your diet.

The study was published in the European Journal of Nutrition.

Source: Edith Cowan University