IBM has announced that its first-of-a-kind hot water-cooled supercomputer has been installed at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich). Named the Aquasar, the system not only consumes up to 40 per cent less energy than an air-cooled machine but the direct utilization of waste heat in the building's heating system translates to an 85 per cent cut in carbon dioxide emissions.

During warm summer months, one of the best places to work is in the server room of a networked office building or data center that uses cool air to prevent processor overheating. Such systems though are not too energy efficient so IBM started on a novel approach to cooling servers about a year ago as part of an initiative to create new technologies to solve business problems. Using warm water as a coolant might seem counter intuitive but the results speak for themselves.

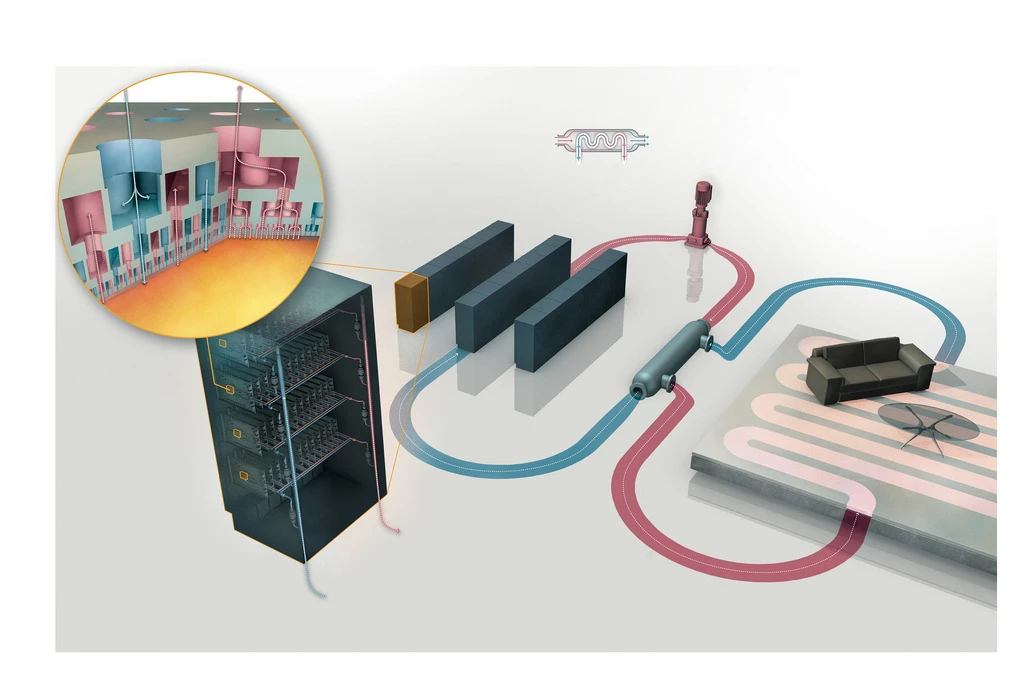

Installed at the Department of Mechanical and Process Engineering at ETH Zurich, an IBM BladeCenter Cluster is comprised of three IBM BladeCenter H chassis with a total of 33 IBM BladeCenter QS22 servers (two IBM PowerXCell 8i Processors each) and nine IBM BladeCenter HS22 servers (two Intel Nehalem EP Processors each). Of those, one chassis is air-cooled for direct comparison and contains 11 QS22 servers and three HS22 servers. The rest have micro-channel liquid coolers attached directly to processors and some components within the server which are then cooled with warm water (up to 60C).

The warm water allows the processors to function well below the maximum allowed operating temperature and the coolant removes heat from the processor "4,000 times more efficiently than air" and in doing so also offers a higher-grade heat at the output, which is passed on to the building's heating system.

"With Aquasar, we make an important contribution to the development of sustainable high performance computers and computer system," said ETH Zurich's Professor Dimos Poulikakos. "In the future it will be important to measure how efficiently a computer is per watt and per gram of equivalent CO2 production."

In high performance LINPACK benchmark testing the Aquasar achieved a performance of six teraflops and had an energy efficiency of about 450 megaflops per watt, whilst also giving back some nine kilowatts of thermal power to the building's heating system.

The next step in the three year Aquasar research program is to focus on the performance and characteristics of the cooling system in order to optimize it further.