Using a new microscopic technique, a team of scientists has identified a previously unknown human anatomical feature. Dubbed the interstitium, the discovery reveals that what was previously thought to be simply dense connective tissue sitting below the skin's surface, and surrounding our organs, is actually a complex series of interconnected, fluid-filled compartments.

The discovery came when a couple of researchers were experimenting with a new type of endoscope that uses a laser and fluorescent dyes to examine living tissue at a microscopic level while probing patients. While examining a patient's bile duct, the researchers identified a pattern of cavities that didn't fit with the known anatomy of the bile duct.

The duo took their anomalous results to pathology expert Neil Theise and the team devised a process to take bile duct biopsies in a novel way without dehydrating the samples. As Theise explains to ResearchGate, "Rather than process the sampled bile duct tissue as usual, with dehydration and chemical fixation to make slides, we quickly froze the tissue, keeping the resected piece as close to the normal living tissue as possible."

The revelation was that what was previously assumed to be just dense connective tissue was in fact an interconnected network of tiny fluid-filled cavities supported by a lattice meshwork of collagen and elastin proteins. Because prior microscopic analysis involved some degree of cellular dehydration these spaces had never been accurately identified, although traces were known and simply assumed to be just artifacts of processing.

"We would often see little "cracks" between collagen bundles in these layers," says Theise. "I was taught, and in turn taught many of my trainees, that these cracks were artifacts of processing. We had pulled the tissue too hard in preparing the slide and separations had formed. But these were not artifacts: these were the remnants of the collapsed spaces. They had been there all the time. But it was only when we could look at living tissue that we could see that."

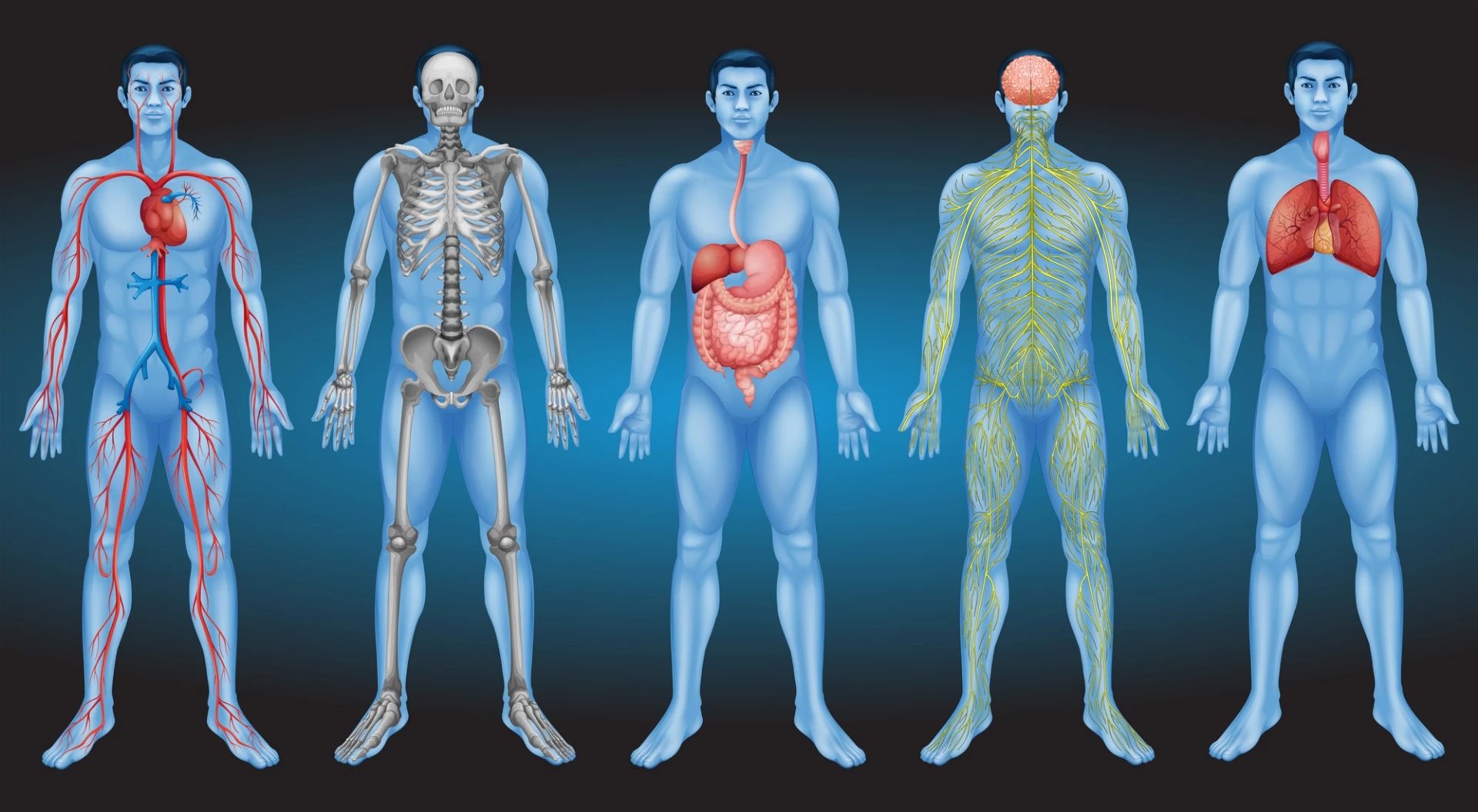

After identifying this surprising space in the bile duct it was quickly seen across the entire human body, from the linings of organs to the fascia surrounding muscles. The interstitium was found to be a kind of pre-lymph system draining fluid into the body's vital lymphatic systems.

The implications of the research are fascinating with Theise suggesting that the interstitium could be a fundamental force in driving cancer metastasis as well as offering a biological explanation for the reported efficacy of techniques such as acupuncture.

But perhaps the most controversial suggestion of the research is that the interstitium should be classified as a new organ. Theise suggests the interstitium fits all the criteria for the definition of an organ, potentially making it the 80th organ to be classified in the human body.

"The definition of 'organ' is imprecise, but usually implies that there is a unity and uniqueness of structure or of function," says Theise. "This space has both: unique properties and structures not seen elsewhere and functions that are highly specific and dependent on the unique structures and cell types that form it."

But not everyone is convinced. While the discovery of the interstitium is inarguably a significant scientific achievement that could lead to a new understanding of the human body, a huge amount of research is yet to be done to determine its function and how it affects the rest of our body. Michael Nathanson, from the Yale School of Medicine, was not involved in this new research and is skeptical of the "organ" designation.

"I would think of this as a new component that is common among a variety of organs, rather than a new organ in and of itself," says Nathanson in an interview with CNN. "It would be analogous to discovering blood vessels for the first time, in that they are in every organ but they aren't an organ themselves."

Despite the semantic argument over classification, the discovery of this new anatomical feature is undoubtedly important and it highlights with exciting clarity that we still have so much more to learn about how our complex human body functions.

The research was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Source: NYU School of Medicine