If you're designing a plastic for applications such as food packaging, you want it to stay clean but you don't want it to stick around for centuries once discarded. A new lotus-leaf-inspired material may fit that bill.

Created by scientists at Australia's RMIT University, the transparent bioplastic is composed primarily of plant-derived starch and cellulose.

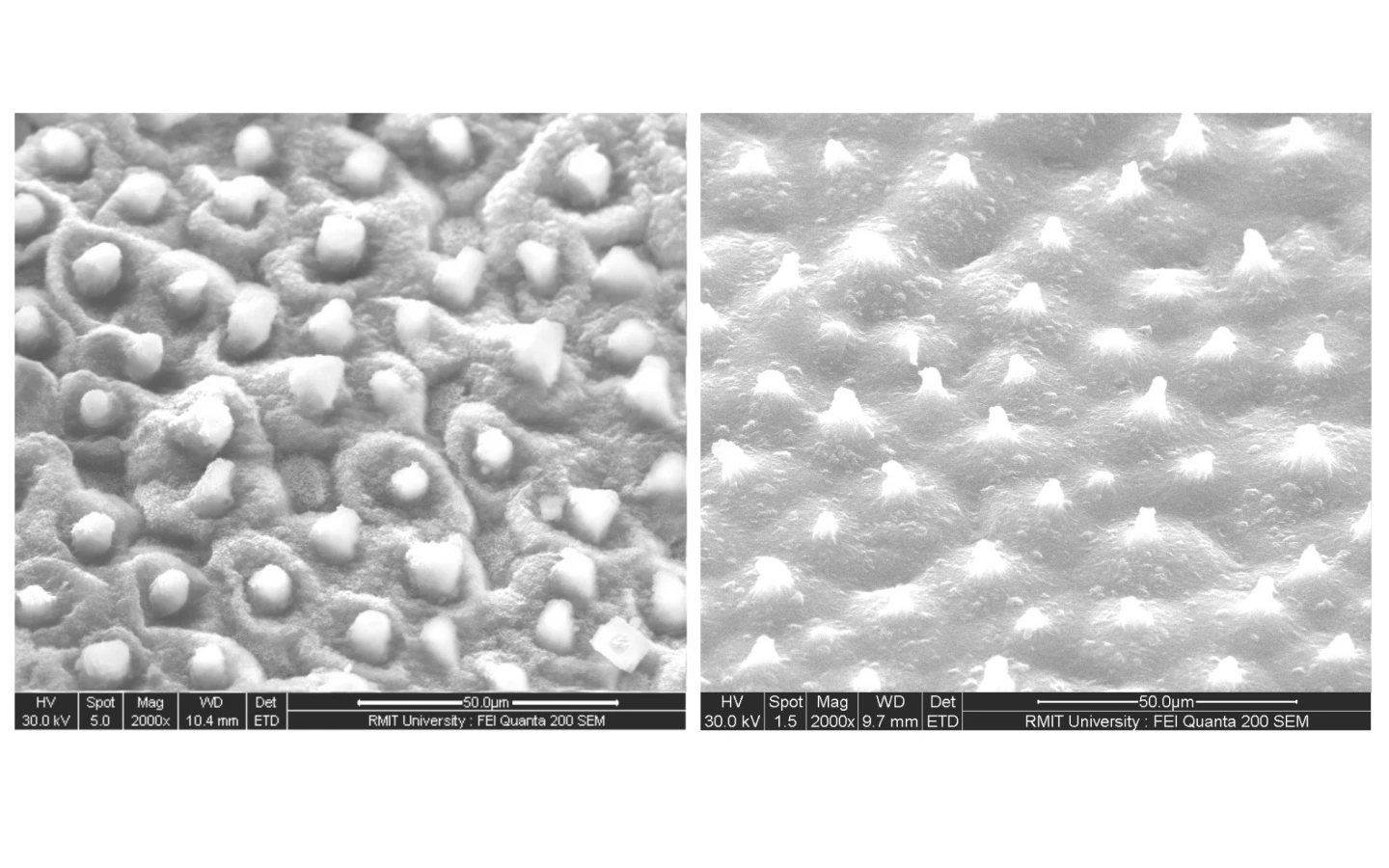

Its surface resembles that of the lotus leaf, in that it's made up of an array of microscopic, closely spaced pillar-like structures. Whereas each pillar on the plant is topped with a waxy substance, the pillars on the plastic are topped with a slippery organic polymer known as PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane).

When a water droplet lands on the plastic – or on the leaf – the pillars suspend it above the underlying main surface, instead of allowing it to flatten out. As a result, the droplet ends up rolling off, collecting whatever dirt particles it encounters along the way.

In the case of the plastic, the tiny pillars remain intact even after being scratched with abrasives, or exposed to acid, ethanol or heat. And the scientists claim that when the material is placed in ordinary soil, it is quickly broken down by naturally occurring bacteria and other organisms. By contrast, some other biodegradable plastics will only break down if subjected to high temperatures or specific industrial processes.

"We designed this new bioplastic with large-scale fabrication in mind, ensuring it was simple to make and could easily be integrated with industrial manufacturing processes," said the lead scientist, Mehran Ghasemlou. "Our ultimate aim is to deliver packaging that could be added to your backyard compost or thrown into a green bin alongside other organic waste, so that food waste can be composted together with the container it came in, to help prevent food contamination of recycling."

The team is already working with one bioplastics company, but is also looking for additional partners that may be interested in commercializing the technology. Papers on the research were recently published in the journals Science of the Total Environment and ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces.

Source: RMIT University