It's long been assumed that when a metal structure like a bridge or an engine develops a crack, it will only get worse over time. But that might not be the case, based on what researchers have just observed happening in a tiny piece of platinum.

From ceramics to car coatings to concrete and even a bioplastic inspired by squid teeth, the scientific community has been busy creating materials that can repair themselves after damage, a property known as self healing. But when it comes to metals, self-healing from the tiny fractures wrought by time known as fatigue damage has remained elusive.

"Cracks in metals were only ever expected to get bigger, not smaller," said Brad Boyce, a scientist at Sandia National Laboratories. "Even some of the basic equations we use to describe crack growth preclude the possibility of such healing processes."

That's why Boyce and his colleagues from Texas A&M University were stunned when they saw a nanoscale piece of platinum mend itself back together after it had been fractured.

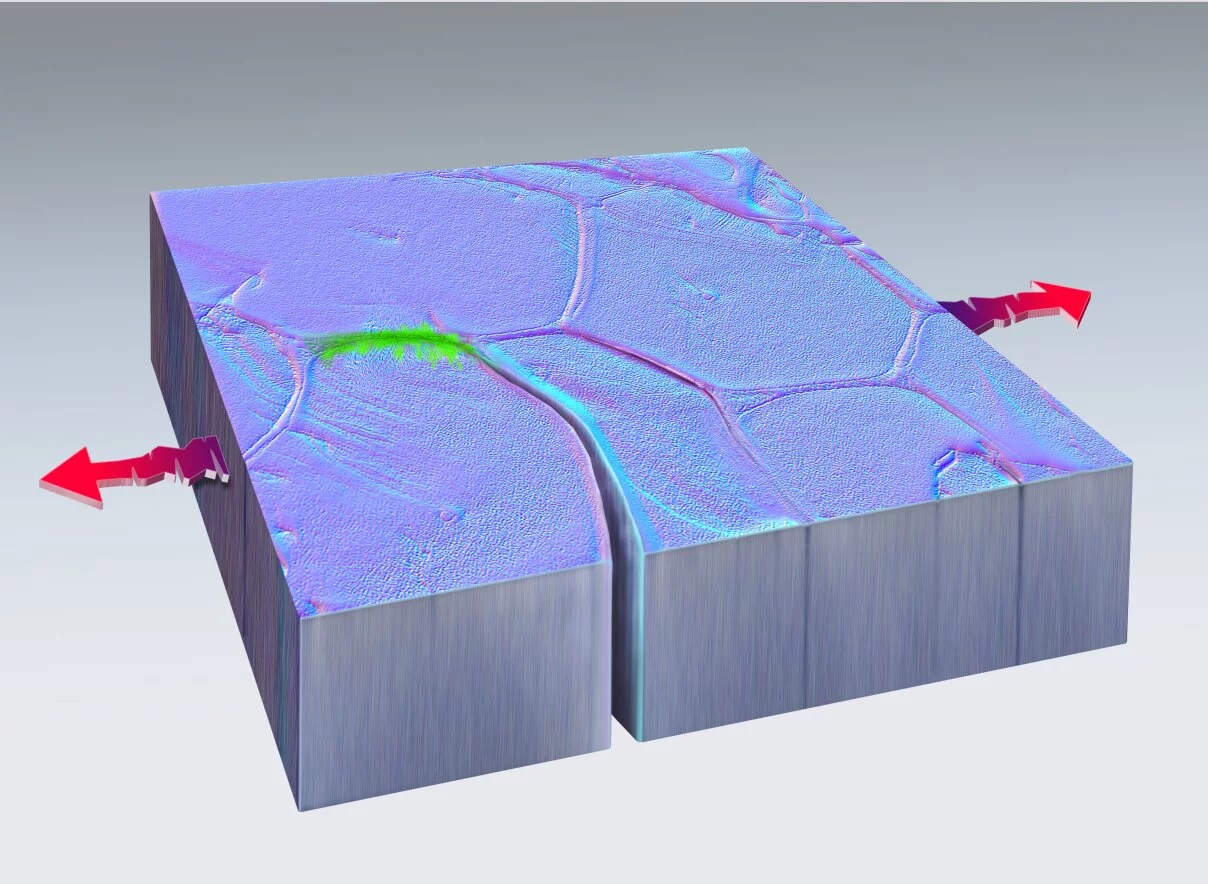

The team was trying to investigate how cracks formed in the metal using an electron microscope technique that involved pulling on the material 200 times per second. While the technique led to breaks in the platinum, about 40 minutes into the experiment, the unexpected happened: a small section of damage knitted itself back together without any interference from the researchers, in much the same way human skin heals after a cut.

"This was absolutely stunning to watch first-hand," said Boyce, who is the lead author on a paper describing the finding. "What we have confirmed is that metals have their own intrinsic, natural ability to heal themselves, at least in the case of fatigue damage at the nanoscale."

The finding has the researchers believing that if the mechanism behind the spontaneous repair can be understood and harnessed, it could change the fundamental way engineers design for and think about stress fractures caused by wear and tear in metal-based structures.

Of course, the researchers are also quick to point out that not only do they not quite understand how the platinum "cold welded" itself back together, but that their discovery took place at the nanoscale in a vacuum, so there's no telling if the findings will translate to larger-scale structures in the real world.

"The extent to which these findings are generalizable will likely become a subject of extensive research," Boyce added.

"My hope is that this finding will encourage materials researchers to consider that, under the right circumstances, materials can do things we never expected," said Michael Demkowicz, a Texas A&M professor who theorized the self-healing potential of metals in 2013. After being informed of the new findings by Boyce, Demkowicz ran a computer model simulation of the findings and confirmed that they matched those he theorized 20 years ago.

The research has been published in the journal Nature.

Source: Sandia National Laboratories