As one of the most commonly used plastics in the world, polypropylene presents a global environmental problem because of issues related to its recycling. Researchers have developed a new way of breaking down this troublesome plastic by enlisting the help of a couple of common fungi.

Most plastics aren’t readily degradable and take decades to biodegrade, resulting in the pollution of land and marine ecosystems. One of those plastics, polypropylene (PP), is used in everything from plastic packaging to furnishing and toys. But in terms of plastic waste, PP is over-represented.

Mainly due to its short life span as packaging and the fact that it gets contaminated by other plastics, PP collected at the curbside tends not to be separated out when it reaches recycling facilities, so it ends up in landfill. In 2015, the world produced 75 million tons (68 million tonnes) of PP, of which only 1% was recycled.

But help may be at hand, thanks to a new recycling technique developed by researchers at The University of Sydney with the help of some unassuming fungi.

“Plastic pollution is by far one of the biggest waste issues of our time,” said Amira Farzana Samat, lead author of the study. “The vast majority of it isn't adequately recycled, which means it often ends up in our oceans, rivers and in landfill. It’s been estimated that 109 million tonnes (120 million tons) have accumulated in the world’s rivers and 30 million tonnes (33 million tons) now sit in the world’s oceans – with sources estimating this will soon surpass the total mass of fish.”

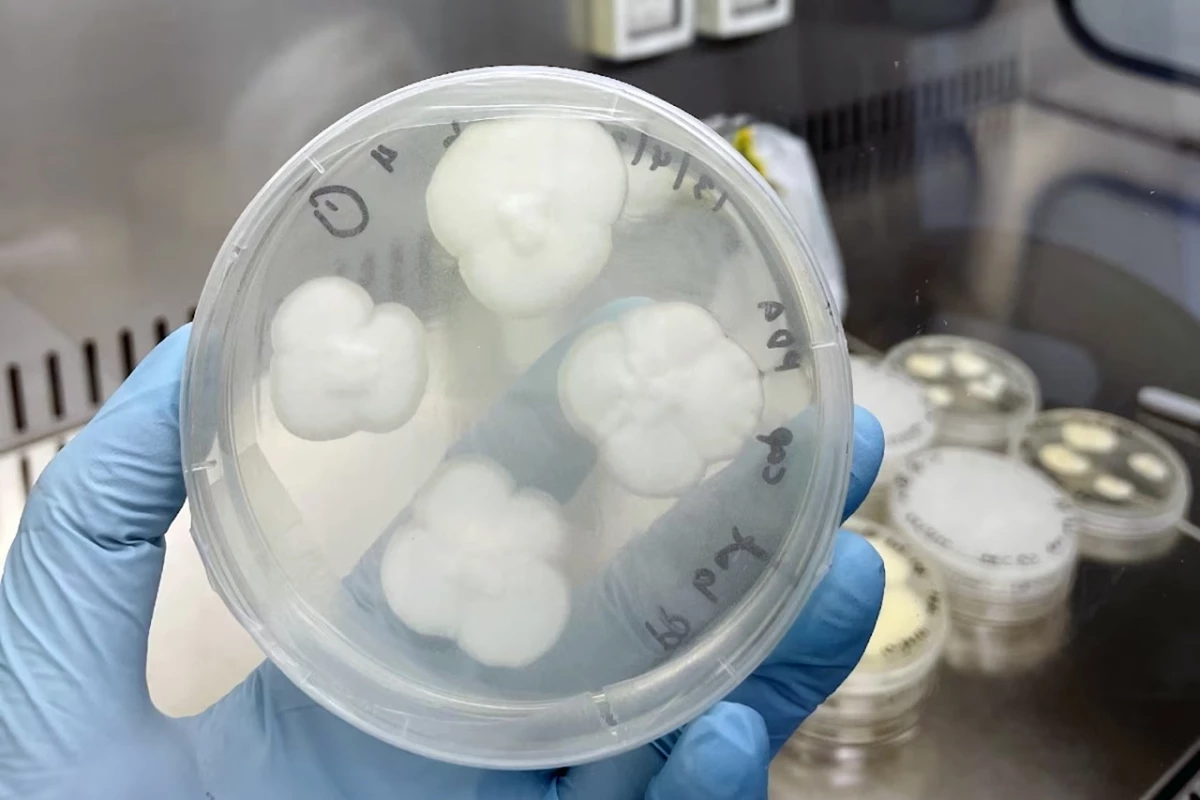

The researchers turned to two fungi commonly found in soil and plants, Aspergillus terreus and Engyodontium album.

“Fungi are incredibly versatile and known to be able to break down pretty much all substrates,” said Dee Carter, co-author of the study. “This superpower is due to their production of powerful enzymes, which are excreted and used to break down substrates into simpler molecules that the fungal cells can then absorb.”

The PP was pre-treated with one of either UV light, heat, or Fenton’s reagent, an acidic solution of hydrogen peroxide and ferrous iron that’s often used to oxidize contaminants.

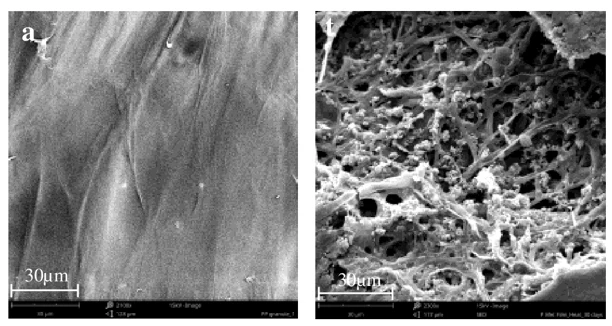

In a Petri dish, the fungi were then applied to the treated PP and the degree of deterioration analyzed using microscopy. The researchers found that the fungi were able to break down PP more effectively when it was pre-treated with UV light or heat. The fungi made relatively fast work of the PP, reducing it by 21% over 30 days and by 25% to 27% over 90 days.

“We need to support the development of disruptive recycling technologies that improve the circularity of plastics, especially those technologies that are driven by biological processes like in our study,” said Ali Abbas, corresponding author of the study. “It is important to note that our study did not yet carry out any optimization of the experimental conditions, so there is plenty of room to further reduce this degradation time.”

Further research will ascertain the biochemical processes underlying this fungi-driven degradation but for now, the researchers plan to enhance the efficiency of their degradation method before seeking investors with a view to commercialization.

The study was published in the journal NPJ Materials Degradation.

Source: University of Sydney