Scientists working with an experimental class of materials have made a breakthrough that could shape a new generation of electronic devices. The researchers’ creation is likened to a conductive “Play-Doh” that can be easily shaped, combining two characteristics in a way they say defies a theoretical explanation.

Materials that conduct electricity such as aluminum, copper or other metals tend to have some things in common. They consist of neat rows of atoms or molecules arranged in a tight configuration, which was thought to be crucial to allow electrons to travel freely through the material.

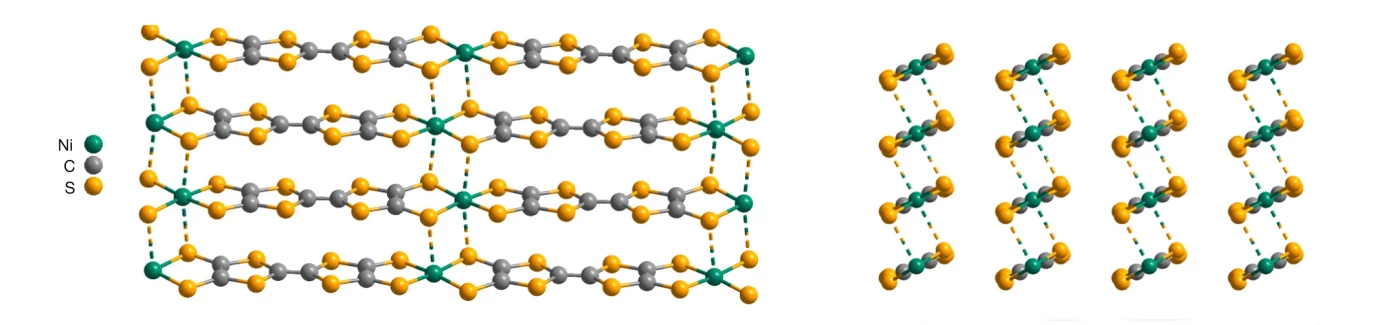

University of Chicago researcher Jiaze Xie had been exploring other possibilities. He was experimenting with materials based on molecular strings made of carbon and sulfur, interspersed with nickel atoms, and produced some unexpected results. To his and the team’s surprise, the material turned out to be a very efficient conductor of electricity, and was able to maintain its performance in a range of inhospitable conditions.

“We heated it, chilled it, exposed it to air and humidity, and even dripped acid and base on it, and nothing happened,” said Xie, who is now at Princeton University.

The material’s conductive abilities appear in conflict to its disordered molecular structure. After testing and simulations, the researchers believe this is due to a lasagna-like configuration in which the material forms layers like sheets of pasta, which allows electrons to travel both horizontally and vertically, even when those layers rotate out of alignment.

“From a fundamental picture, that should not be able to be a metal,” said senior author John Anderson. “There isn’t a solid theory to explain this.”

The scientists say the conductive material is unprecedented in the way it can both be pliable and conduct electricity, with Anderson likening it to “conductive Play-Doh – you can smush it into place and it conducts electricity.”

Through chemical treatments, scientists have been able to make conductors with organic materials that are easier to process and offer some flexibility, but their conductivity typically wanes under high temperatures or when exposed to moisture. With an ability to withstand these factors, the scientists believe they’ve laid the groundwork for a new class of conductive materials.

“In principle, this opens up the design of a whole new class of materials that conduct electricity, are easy to shape, and are very robust in everyday conditions,” said Anderson.

Working in its favor is the fact that the material can be made at room temperature, unlike metals or typical conductor materials that need to be melted into shapes to suit different electronic devices. And the team hopes to further expand the capabilities by experimenting with different forms and functions.

“We think we can make it 2D or 3D, make it porous, or even introduce other functions by adding different linkers or nodes,” said Xie.

The research was published in the journal Nature.

Source: University of Chicago