Building on the trailblazing carbon-fiber-as-a-battery work started at Sweden's Chalmers University of Technology, deep-tech startup Sinonus is working to commercialize a groundbreaking new breed of multifunctional carbon fiber. In its vision, the wonder-composite will save weight not merely because of its famously low base weight but because it will double as a set of energy-managing electrodes, becoming a structural battery that cuts reliance on the traditional standalone battery pack. The company believes this style of energy storage could help revolutionize everything from electric aircraft to windmills.

Imagine an electric car that isn't weighed down by a huge, kilowatt-hour-stuffed battery. It wouldn't need as much power to drive it forward and could rely on a smaller motor, saving yet more weight. Or imagine an eVTOL that could take off without lifting a lithium-ion anchor that requires it to be back on the ground within an hour for charging. Or a windmill with blades that work as their own batteries, storing energy during low demand periods for distribution at peak hours.

Sinonus hopes to write a future in which all those visions come true. It's hard at work on a new breed of smart carbon fiber capable of serving as the electrodes of an integrated battery.

The Swedes have long been working on structural composites capable of storing electricity. We first heard tell of the work over a decade ago when Volvo publicized its participation in a research project it had undertaken in cooperation with a number of academic partners, including Chalmers.

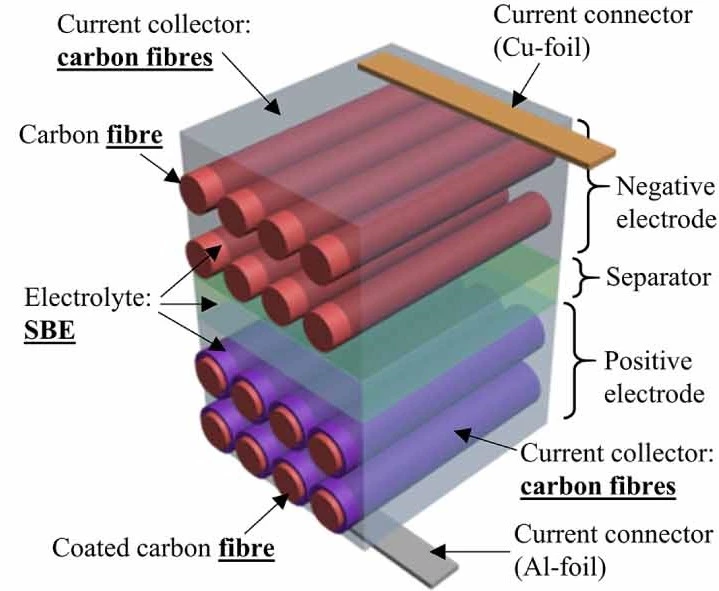

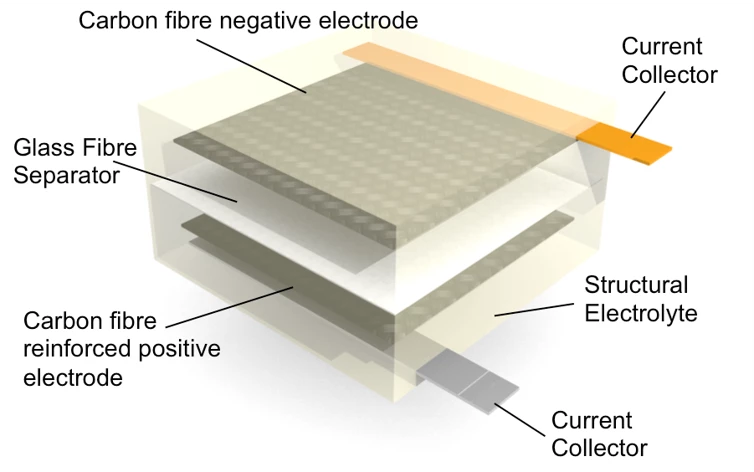

Chalmers picked up the ball and ran with it, and a few years later, it had identified a specific subset of carbon fibers that could deliver just the right blend of electrical conductivity and structural stiffness. It eventually went on to develop a prototype "massless" carbon battery.

In 2022, the university and VC firm Chalmers Ventures spun off the project into its own company, Sinonus. The startup sums up its purpose as "multipurpose," pursuing materials that serve two or more functions in an effort to conserve overall resources.

In an EV, for instance, its carbon fiber battery system would presumably weigh the same as or less than traditional steel and aluminum structural components but with the advantage of storing its own power and eliminating the need for a large, heavy battery pack.

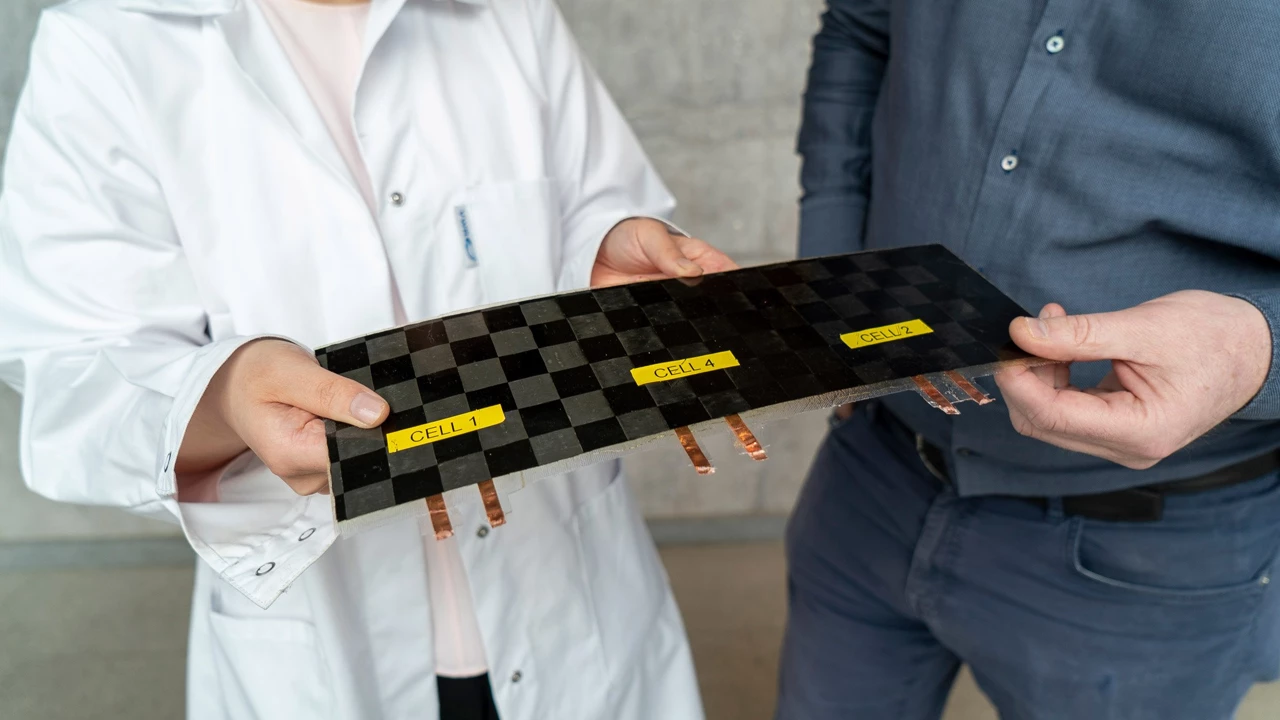

This month, Sinonus appointed Markus Zetterström as its new CEO, responsible for commercializing carbon fibers that double as electrodes. While the company doesn't estimate when that commercialization effort might result in the first market-ready products, the tech has come a long way since those rough Volvo prototype days.

Sinonus says that it has already proven its concept in the lab by replacing AAA batteries with its carbon-electrode battery in low-power applications. To go where it wants to go, it will have to scale power up in a major way, first with devices like IoT hardware and computers, and eventually upward to power-hungry equipment like electric cars and aircraft.

“Storing electrical energy in carbon fiber may perhaps not become as efficient as traditional batteries, but since our carbon fiber solution also has a structural load-bearing capability, very large gains can be made at a system level,” Zetterström explains.

Of course, that "not as efficient as traditional batteries" isn't something to skip over. Sinonus has not yet published an energy-density figure for its battery concept, but 2021's Chalmers lab prototype had a paltry density of 24 Wh/kg, a fraction of what you get from the modern lithium-ion packs found in everything from smartphones to electric cars and airplanes.

Sinonus remains optimistic, pointing to a previous Chalmers study that found structural carbon fiber batteries had the potential to increase EV range by up to 70%. The lower energy density could also prove a positive, the company suggests, eliminating volatile chemicals and high energy concentrations to ultimately decrease the chances of catastrophic failure.

Cost is another question mark that dangles like a foreboding storm cloud over Sinonus' Gothenburg headquarters. EV batteries are expensive in themselves, but would replacing them with specially sandwiched electrical-grade carbon fiber really be any cheaper?

It sounds like Markus Zetterström has some difficult but fascinating work ahead. We look forward to watching as he and the Sinonus team attempt to find answers to the questions surrounding the structural battery concept and its ultimate market viability.