Analyzing the functional connectivity of different brain networks, researchers found that, compared to a healthy aging brain, Alzheimer’s disease disrupts areas of the brain beyond those relating to memory and is independent of factors typically associated with the disease, such as amyloid beta levels.

Neuroscientists have distinguished brain regions and systems by function for over a century. According to the network approach to brain connectivity, the cognitive dysfunction seen in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) results from the failure of multiple specialized brain systems that are interconnected within a large-scale brain network.

However, it's unclear how brain network changes vary with dementia severity and whether they’re distinct from changes seen in the network of the healthy aging brain. Understanding these changes is important for establishing the cause of AD-related brain and cognitive dysfunction.

Researchers from the University of Texas at Dallas have measured functional brain network organization in people who varied in age and dementia status to ascertain whether there is a difference.

“Some Alzheimer’s disease-accompanied brain dysfunction that goes beyond memory and attention might be detectable at very early stages, even during mild cognitive impairment before a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s,” said Gagan Wig, corresponding author of the study.

The researchers recruited 601 participants, aged 55 to 96, for the study through the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Of the participants, 326 were cognitively healthy, and 275 were cognitively impaired. Memory, mental state, and clinical dementia rating were ascertained at baseline, as was the presence of amyloid beta pathology. Amyloid beta peptides are the main component of the plaques found in the brains of people with AD.

Functional connectivity analyses of the brain use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data to examine how signals from different areas of the brain correlate. Using fMRI and structural MRI images collected as part of ADNI, the researchers calculated each participant’s brain system segregation, a measure of how separated each functional brain system is. The segregation of specific types of brain systems was also calculated, including sensory-motor systems and the so-called association systems, which integrate and retain information and oversee attention, memory and language.

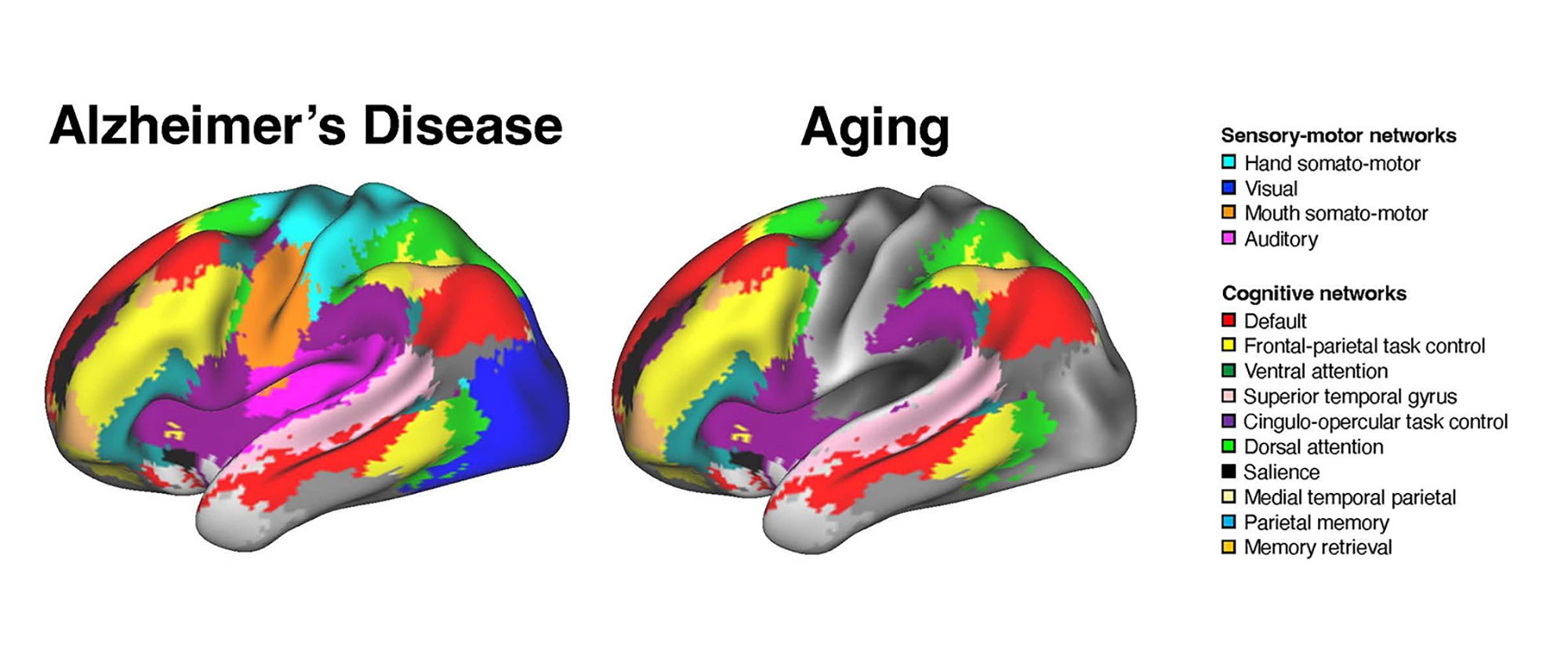

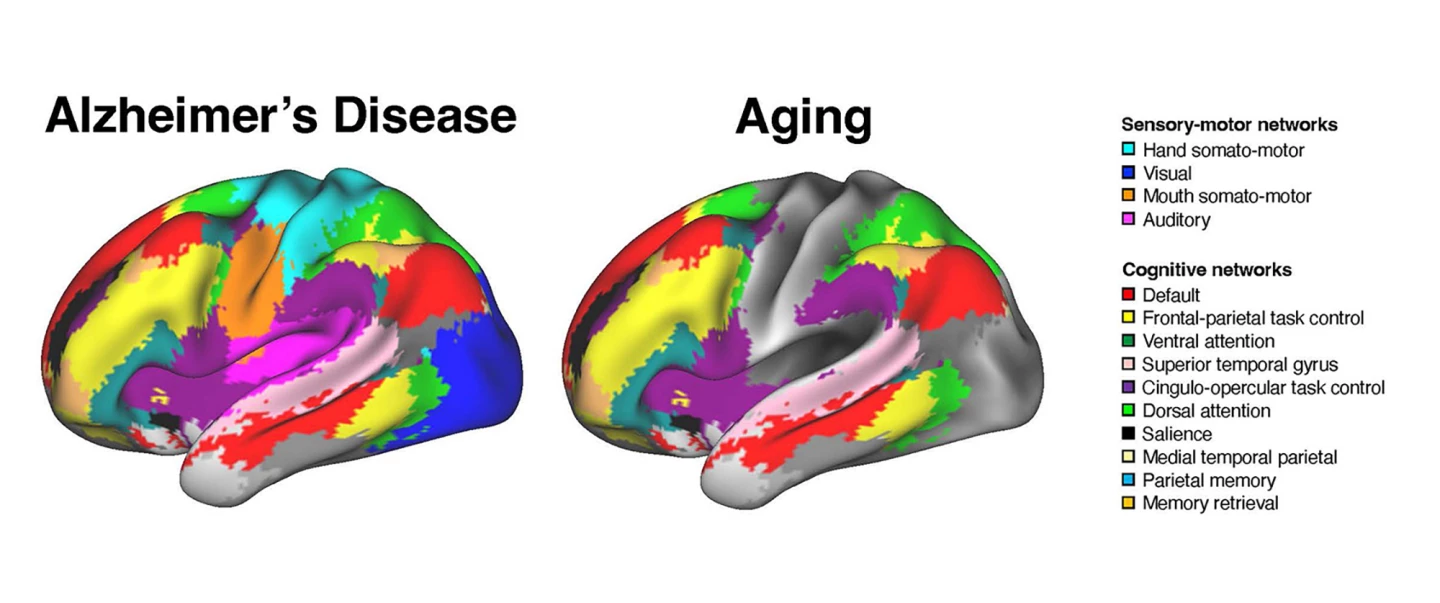

The researchers found that AD and healthy aging were associated with distinct patterns of brain network disruption. AD impacted the connectivity of both the association and sensory-motor networks, whereas aging was limited to a disruption of cognitive networks.

“In healthy aging, changes seem largely focused on association systems,” Wig said. “Sensory and motor systems are generally stable. With the brain-scan data we now have available, we can account for age-related brain differences and observe alterations unique to dementia severity. Exploring this, we found worsening dementia is associated not only with alterations to association systems but also to the sensory and motor systems.”

The researchers say their findings suggest that the network interactions affected in AD are broader than those affected by healthy aging.

“In older adults who don’t show any cognitive impairment, the interactions are primarily among brain regions performing similar functions or within brain systems,” said Ziwei Zhang, the study’s lead author. “However, in patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, the interactions between regions that perform distinct functions – such as visual processing and memory – are also altered.”

AD-related changes in brain networks were independent of other factors typically associated with the disease, such as amyloid beta levels. This might explain why some people with typical Alzheimer’s pathologies like amyloid plaques or tau tangles remain cognitively unaffected.

“We’ve come to realize that the targets we’ve been focusing on might not be sufficient, including the idea of amyloid being the primary culprit of Alzheimer’s disease,” Wig said. “We’ve been seeking other ways of quantifying Alzheimer’s dysfunction, and in this paper, we show that even when you account for amyloid burden, circuit dysfunction is still there.”

This brain-network dysfunction could be a new way of characterizing AD-related cognitive impairment and may provide a target for potential treatment.

“These observations offer important clues toward identifying the types of behavioral deficits that are most impacted at early stages of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia,” said Wig. “As we continue to refine the brain network-based biomarkers of Alzheimer’s, we are honing in on a new, unique source of information to aid both Alzheimer’s diagnosis and for measuring disease risk in otherwise healthy individuals.”

The study was published in the Journal of Neuroscience.

Source: University of Texas at Dallas