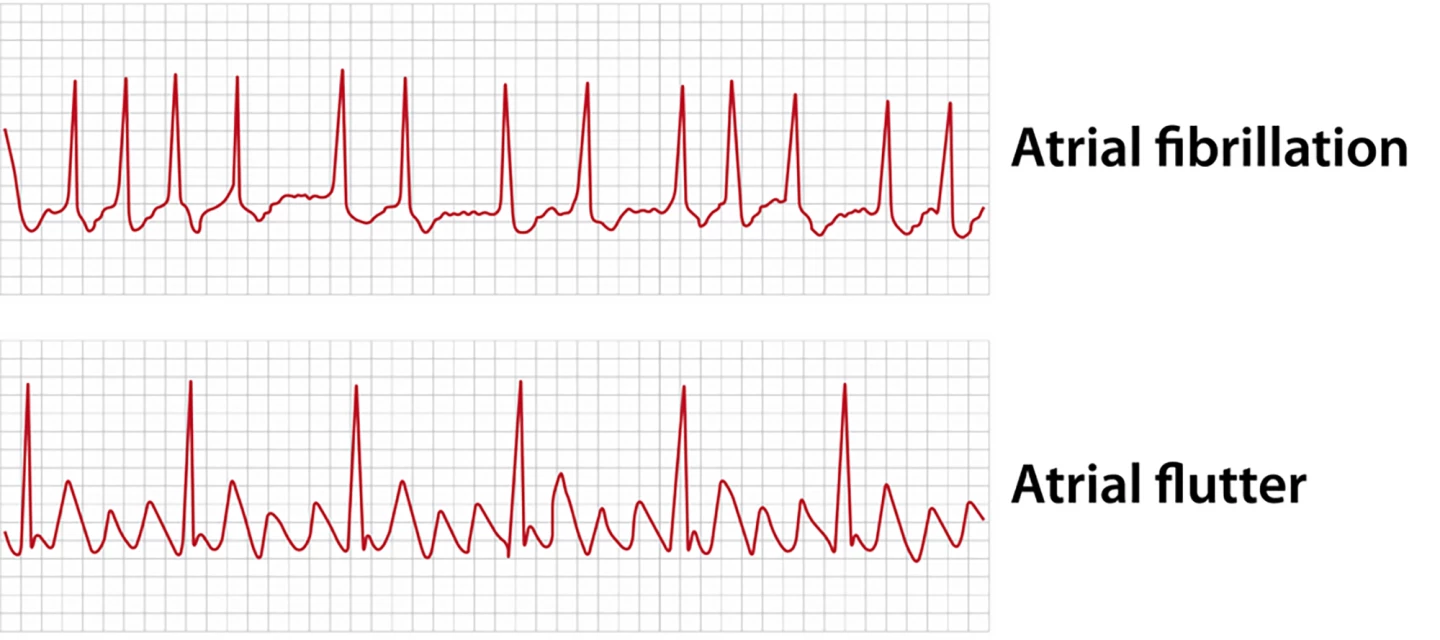

AF, or AFib, and its close medical cousin, atrial flutter, are associated with complications such as stroke, heart failure, and heart attack. While there’s an understandable focus on treating these conditions to prevent acute complications, less research has looked at what’s happening in the long term.

Now, a study led by researchers from the University of Queensland’s (UQ) Faculty of Medicine examined clinical outcomes up to 10 years after an acute hospital admission for AF or atrial flutter. The findings are rather grim.

“AF is the most common heart rhythm disorder and the leading cause of heart-related hospitalizations globally, causing symptoms like palpitations, dizziness, and chest pain,” said Linh Ngo, the study’s lead and corresponding author. “The disorder is closely associated with stroke, but we know much less about the risk of recurrent hospitalizations and other consequences such as heart failure or death.”

The researchers looked at hospital admissions across Australia and New Zealand between 2008 and 2017 for 260,492 adults (49.6% female, mean age 70). AF or atrial flutter was the primary diagnosis. The primary outcome was death from all causes, including deaths that occurred in the community. Secondary outcomes were loss in life expectancy attributable to AF or flutter, associated outcomes (e.g., stroke, heart failure, heart attack) linked to AF or flutter, re-hospitalizations for AF or flutter, and whether the patient was treated by catheter ablation or cardioversion.

Catheter ablation, or cardiac ablation, involves guiding a thin, flexible tube (catheter) to the heart via a blood vessel. Heat or extreme cold is applied to the area that is causing the irregular heart rhythm, forming scars that block the irregular beats. Electric cardioversion is far less invasive. It uses quick, low-energy electric shocks applied to the chest to revert the heart back into a regular rhythm. Chemical or pharmacological cardioversion uses drugs to return the heart to a regular rhythm.

One year after discharge, 91.4% of patients survived, dropping to 72.7% at five years. At 10 years, the survival rate had fallen to 55.2%. Compared with an age, sex, and region-matched general population, patients hospitalized for AF or atrial flutter had, on average, a 2.6-year loss in life expectancy. When different age groups were considered, the loss in life expectancy ranged from 1.6 years in those aged 80 and over to 3.4 years in 35-to-49-year-olds.

In terms of AF-related complications, over the 10-year period, 11% of patients were re-hospitalized for a stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), a brief blockage of blood flow to the brain that may warn of a future stroke. Some 16.8% were re-hospitalized for heart failure, making it the most common AF-associated outcome. Re-hospitalization because of a recurrence of AF or flutter was 21.3% at one year, 35.3% at five years, and 41.2% by 10 years.

During the initial hospitalization, only 0.3% of patients underwent catheter ablation for AF. After discharge and within the 10-year study period, that number rose to 6.5%. Considering catheter ablation is one of the most effective treatments for the condition, that number is both curious and concerning.

“It may mean this procedure [catheter ablation] was underused in Australian and New Zealand hospitals,” said cardiologist Isuru Ranasinghe, a study co-author.

For comparison, a US study published in 2009, a year after the current study commenced, reported that the rate of catheter ablation in AF patients increased from 0.06% in 1990 to 0.79% in 2005.

The study does indicate, said the researchers, that there needs to be a greater focus on the long-term sequelae of AF and atrial flutter.

“Clinicians currently primarily focus on preventing the risk of stroke, but these findings emphasize the need to consider atrial fibrillation as a chronic disease with multiple serious downstream consequences,” Ranasinghe said. “There needs to be a greater focus on preventing recurrent hospitalizations and heart failure.”

They suggest another way to bring down these stark numbers is by enhancing patient education.

“Better patient education in areas such as blood pressure control and weight loss, as well as appropriate preventative therapy in hospital and primary care could improve outcomes for people with AF,” said Ranasinghe.

Americans, while this may be an Australia-New Zealand study, you're not out of the woods. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that, in 2019, AF was mentioned on 183,321 death certificates and was the underlying cause of death in 26,535 of those deaths. And it's estimated that 12.1 million people in the US will have AF by 2030.

The study was published in the European Heart Journal.

Source: UQ