By analyzing the brain waves of improvising jazz musicians, researchers now understand how the brain achieves a creative flow state. The findings have practical implications for anyone – not just musicians – wanting to get ‘in the zone’ to generate creative ideas.

Flow, commonly called being in the zone, is where a person is totally engaged in performing an activity, up to the point where they are hardly self-conscious or conscious of their surroundings. The phenomenon is often used to describe artists and athletes but is aspired to by businesspeople, researchers, educators and, well, anyone who wants to produce creative ideas and products.

There’ve been many studies on flow, but most have relied on participants’ self-reports. Researchers from the Creativity Research Lab at Drexel University in the US are the first to reveal, in a new study, how the brain gets in the zone by analyzing flow-related brain activity during a creative task.

“Flow was first identified and studied by the pioneering psychological scientist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi,” said John Kounios, a corresponding author of the study. “He defined it as ‘a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.’”

A relatable example of musicians entering the flow state appears in the 2020 Disney and Pixar film Soul. When someone spends a lot of time in “The Zone” in the movie, they experience a state of complete absorption and focus. In the video below, some of the movie’s musical artists talk about their own experiences of the phenomenon.

Although flow has been widely studied, there’s no consensus about what it is from the perspective of brain functioning. One theory is that flow occurs when the brain areas that work together when a person daydreams, called the ‘default-mode network,’ generate ideas under the supervision of the ‘executive control network’ in the brain’s frontal lobes. Kounios likens it to someone ‘supervising’ a TV by choosing the movie it streams.

An alternative theory is that years of practicing a task causes the brain to develop a specialized network that produces specific ideas – for example, musical ideas – with little conscious effort. The executive control network relaxes in its supervisory role so the specialized network can run on ‘autopilot’ without interference. Key to this hypothesis is the idea that people without extensive experience or who find it difficult to let go will be less likely to enter a state of creative flow.

The researchers recruited 32 jazz guitarists, some highly experienced and other less so, recording high-density electroencephalograms (EEGs) of brain activity while they improvised to six jazz songs, accompanied by drums, bass and piano. Participants were asked to rate the intensity of their flow experience for each improvisation or 'take.' Each take was also judged by four jazz experts individually to objectively ascertain the participants’ level of expertise.

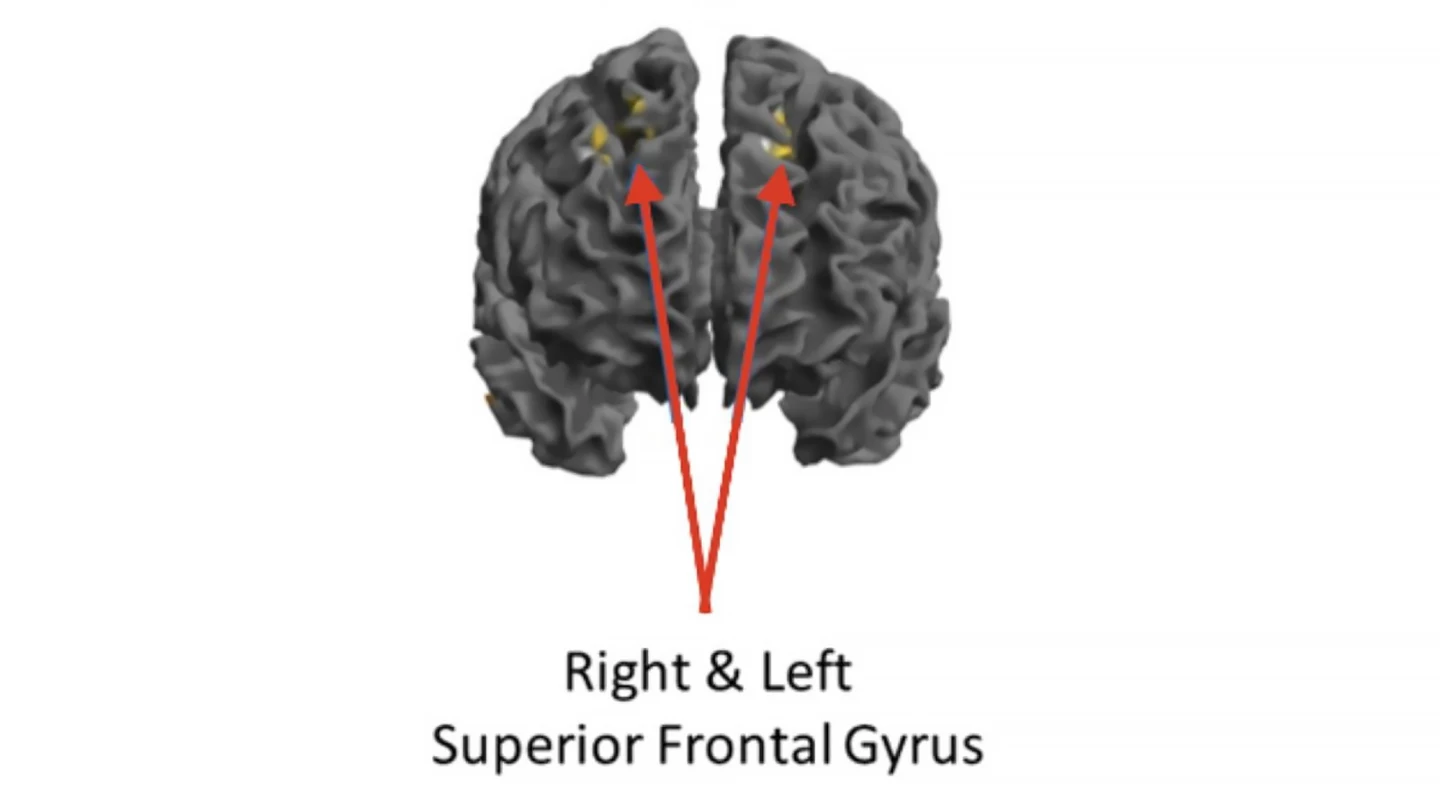

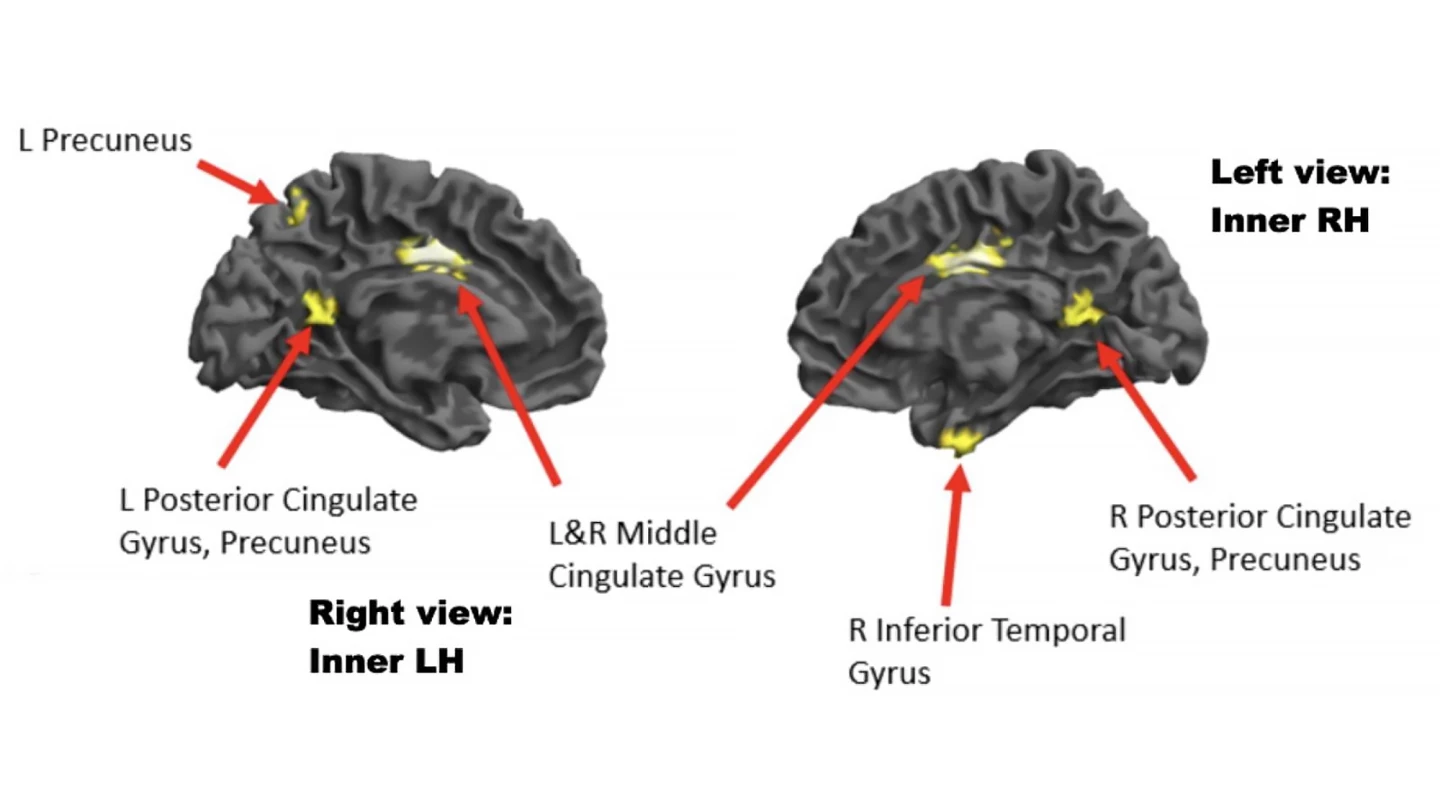

Based on the participants’ ratings, the researchers found that the highly experienced musicians experienced flow more often and more intensely than musicians with low experience. When they analyzed the EEGs to see what brain regions were associated with high- and low-flow takes, they found that a high-flow state was associated with increased activity in left-sided brain areas associated with listening to and playing music. Importantly, in a high-flow state, activity decreased in frontal areas associated with conscious control or letting go.

For the high-experience musicians, the high-flow state was associated with increased activity in auditory and visual areas and reduced activity in key parts of the default-mode network. This suggested that the default-mode network wasn’t contributing much to flow-related idea generation. In contrast, the low-experience musicians showed little flow-related brain activity.

Overall, the findings supported the ‘expertise-plus-release of control’ hypothesis of creative flow, which has practical implications for those wanting to enter the flow state.

“A practical implication of these results is that productive flow states can be attained by practice to build up experience in a particular creative outlet coupled with training to withdrawn conscious control when enough expertise has been achieved,” Kounios said. “This can be the basis for new techniques for instructing people to produce creative ideas.”

While this study was concerned with musicians, the researchers say that their findings extend to anyone wanting to be innovative – in any field.

“If you want to be able to stream ideas fluently, then keep working on those musical scales, physics problems or whatever else you want to do creatively – computer coding, fiction writing – you name it,” said Kounios. “But then, try letting go. As jazz great Charlie Parker said, ‘You’ve got to learn your instrument. Then, you practice, practice, practice. And then, when you finally get up there on the bandstand, forget all that and just wail.’”

The study was published in the journal Neuropsychologia.

This video, produced by the National Science Foundation, which funded the research, explains the study and its findings.

Source: Drexel University