Scientists are reporting some promising findings from a large prostate cancer trial, where patients were administered a drug typically used to treat breast cancer. The drug proved more effective than standard hormone treatments at applying the brakes to the disease, with the scientists hopeful it can lead to approval this year of the first gene-targeted drug to tackle prostate cancer.

The drug investigated in this study is called Olaparib, and is already licensed for use as a treatment for breast and ovarian cancers. Taken as a pill, the drug works by inhibiting a protein called PARP, which plays an important role in repairing damaged DNA.

While boosting the activity of PARP would normally be a desirable outcome, and may open up exciting opportunities when it comes to anti-aging or treating radiation damage, the opposite is true of this protein in cancer cells. Some cancer cells shaped by genetic mutations rely on PARP to maintain healthy DNA and continue to grow, which presents researchers with a golden opportunity to intervene.

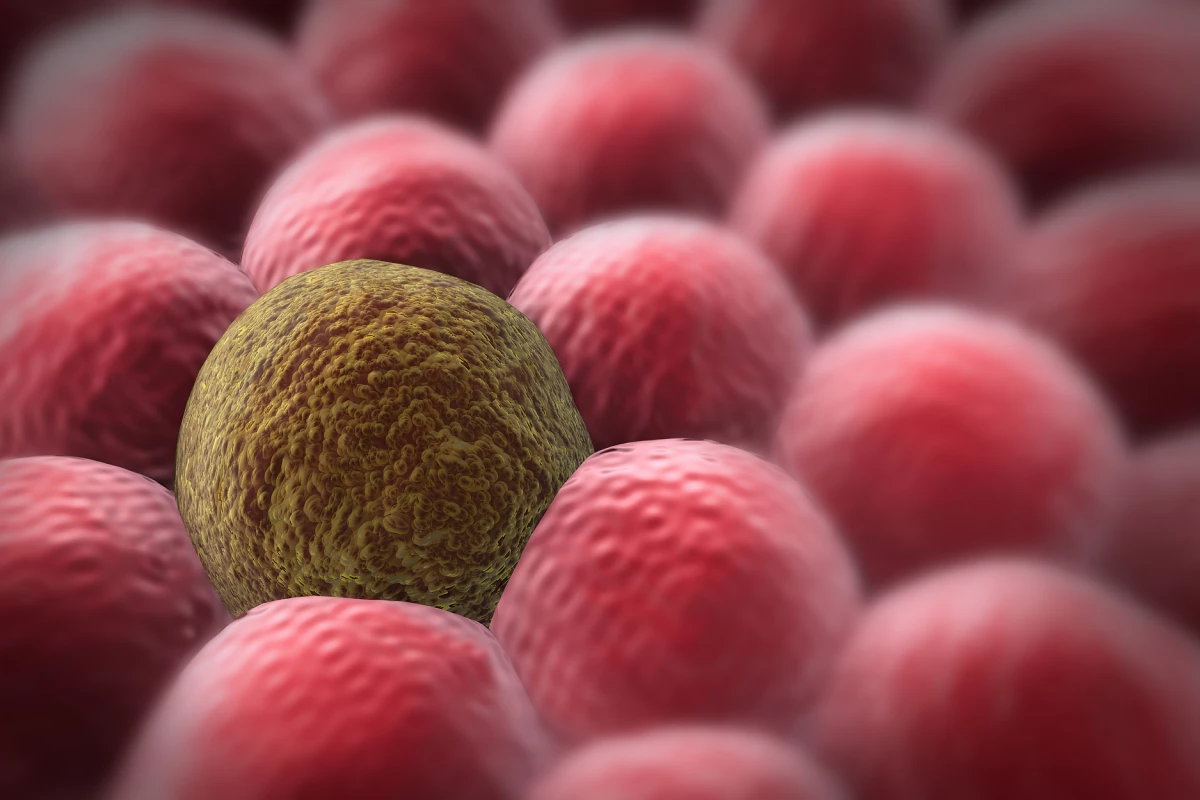

Olaparib is a drug that specifically targets cells bearing these DNA repair mutations, blocking the activity of the PARP protein and causing the cancer cells to die. The international team behind the new study, including scientists from London’s Institute of Cancer Research and Northwestern University in the US, set out to see if it could have similar effects on well-progressed prostate cancer.

The scientists enlisted 387 male subjects with advanced prostate cancer, all with alterations in 15 DNA repair genes. The patients were randomly administered either olaparib or the standard treatment of hormone therapy, which involves drugs called abiraterone and enzalutamide.

All subjects who received olaparib experienced a delayed progression of the disease, with the average length of time before the cancer got worse being 5.8 months, compared to 3.5 months in those receiving the conventional hormone treatment.

The results were even more impressive among patients with three mutations in particular that affect the BRCA1, BRCA2 or ATM genes. Here, progression of the disease was delayed by an average of 7.4 months, compared to just 3.6 months among the control group.

Survival of these men was 19 months when receiving olaparib, and just 15 months for those using the hormone treatment, even though 80 percent of those subjects switched to olaparib when the cancer began to progress. However, the scientists note the need for further studies over longer time frames to draw solid conclusions regarding survival rates.

The team believes these results place olaparib on the precipice of approval as the first genetically targeted treatment for prostate cancer in Europe and the US later this year, though the researchers will carry out further research as the next steps.

“It’s exciting to see a drug which is already extending the lives of many women with ovarian and breast cancer now showing such clear benefits in prostate cancer too,” says study co-leader Professor Johann de Bono from the The Institute of Cancer Research. “I can’t wait to see this drug start reaching men who could benefit from it on the NHS (National Health Service) – hopefully in the next couple of years. Next, we will be assessing how we can combine olaparib with other treatments, which could help men with prostate cancer and faulty DNA repair genes live even longer.”

The research was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Source: Prostate Cancer Foundation