Researchers have identified the likely ‘cells-of-origin’ that can lead to breast cancer in women who carry a mutated BRCA2 gene, and uncovered their vulnerability. Targeting the cells with an existing cancer drug slowed tumor progression, opening the door to a new breast cancer prevention strategy.

Everyone has two copies of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, one inherited from their mother and one from their father, that help protect against breast, ovarian, prostate and pancreatic cancers. However, women who inherit and carry a faulty BRCA2 gene have close to a 70% chance of developing an aggressive form of breast cancer over their lifetime, necessitating regular screening from an early age. To reduce their chances of getting cancer, some carriers opt to have a preventive mastectomy.

Now, researchers from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (WEHI) in Melbourne, Australia, have identified the likely ‘cells-of-origin’ of breast cancer in BRCA2 carriers, marking a potential treatment target for the disease, and found an existing drug that may slow tumor development.

The researchers compared cancer-free breast tissue samples from BRCA2-mutation carriers and non-carriers and identified a population of cells that divided more quickly in the majority of samples from women with the faulty gene.

“Given they were found in most of the BRCA2 tissue samples from healthy females, we believe these may be the cells-of-origin that lead to future breast cancers in women that carry the BRCA2 mutation,” said Rachel Joyce, lead author of the study.

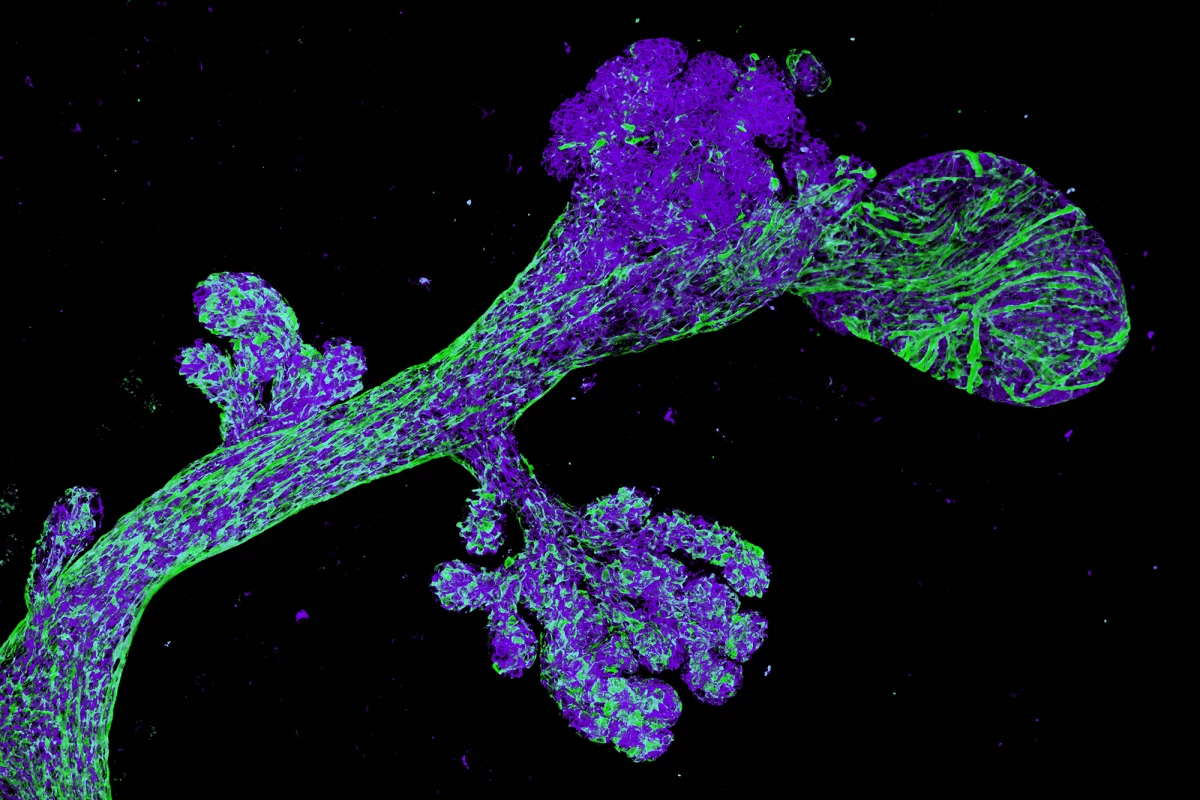

The aberrant cells, a subset of breast ductal cells called luminal progenitor cells, stood out to the researchers because of their altered protein production, which is critical for the correct growth and functioning of body tissues.

“These changes may also make the cells more vulnerable to certain therapies aimed at preventing or delaying breast cancer development,” said Rosa Pascual, joint lead author.

To test for this vulnerability, the researchers developed a BRCA2 model with similar aberrant cells and treated them with everolimus, an existing cancer drug approved to treat patients with relapsed breast cancer. Everolimus selectively targets a protein complex called the mammalian – or mechanistic – target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), which functions as a nutrient sensor and controls protein synthesis, inhibiting the growth and aggressiveness of breast cancer cells.

“Through pinpointing this vulnerability in protein production, we were able to show that pre-treatment with this drug delayed the formation of tumors in the pre-clinical model,” said joint corresponding author Jane Visvader. “This raises the possibility that targeting specific aspects of protein production in this way could represent a new breast cancer prevention strategy for women with a faulty BRCA2 gene.”

The study’s findings are an important first step toward the goal of preventive treatments for breast cancer in BRCA2 carriers; however, there is more work to be done before they can be applied clinically.

“While everolimus did delay tumor development in the lab, this drug can have side effects, which might limit its capacity to be used as a preventative treatment,” said Geoff Lindeman, the study’s other corresponding author. “Our team want to further explore which specific parts of protein processing are dysregulated, and use this information to develop more selective and tolerable preventative treatments. There’s still a way to go, but we’re a big step closer.”

The current study advances the WEHI team’s ongoing research into breast cancer.

“A few years ago, we identified the likely cells-of-origin for breast cancer in females carrying a fault in the BRCA1 gene, which is also associated with a high risk of developing breast cancer,” Lindeman said. “That research has since led to an international breast cancer prevention study (BRCA-P). We hope that our new findings will now inform future treatment and prevention for women with a faulty BRCA2 gene.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Cell Biology.

Source: WEHI