An international team of neuroscientists has for the first time identified five distinct subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease, in what could be a breakthrough for treatment approaches and efficacy. They call for researchers and medical professionals to look at the disease not as a single diagnosis but five specific types of Alzheimer’s.

Scientists from the Alzheimer Center Amsterdam, the University of Amsterdam, and Maastricht University, along with neurodegenerative disease specialists from the US, Belgium, the UK and Sweden found five categories of fluid surrounding the brains of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. The team’s earlier research had identified three distinct subtypes, but by looking at more proteins and patients in this latest study, two more emerged.

Central to the study was the use of mass spectrometry proteomics to analyze cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in 419 patients and 187 control participants. CSF, which is clear liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord, is considered a ‘window to the brain.’ While it provides a crucial protective buffer, CSF also contains proteins that are made in the brain and released into the fluid. As such, three CSF biomarkers – Aβ42, total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) – are widely recognized as the AD disease profile and are an important diagnostic tool.

In the latest findings, the team identified 1,058 proteins in CSF that differed between the two cohorts tested. These proteins were then found to be linked to specific, different molecular processes involved in AD progression.

Interestingly, each of the five subtypes was also linked to a unique genetic risk profile, suggesting there are broad biological factors associated with the disease.

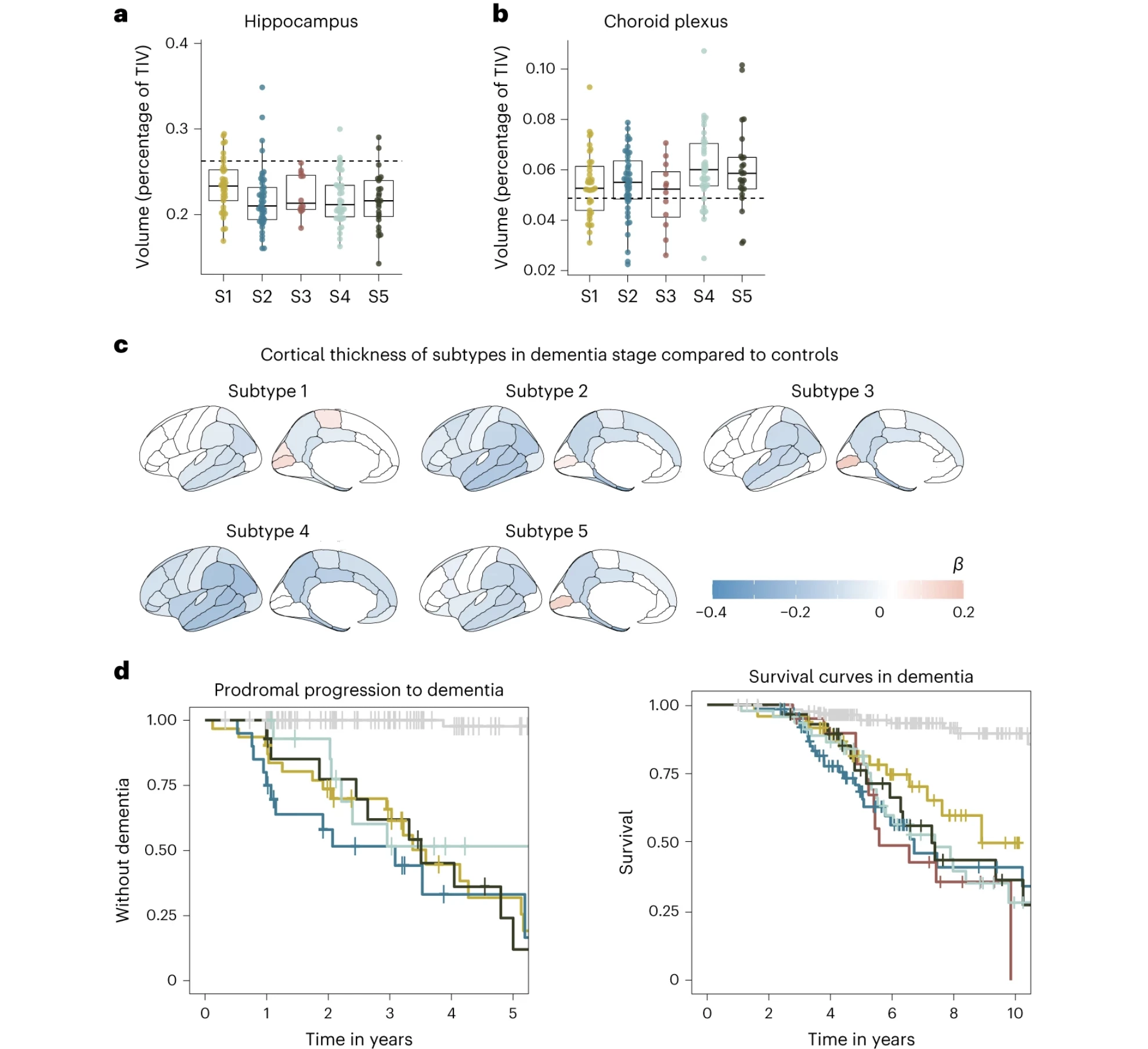

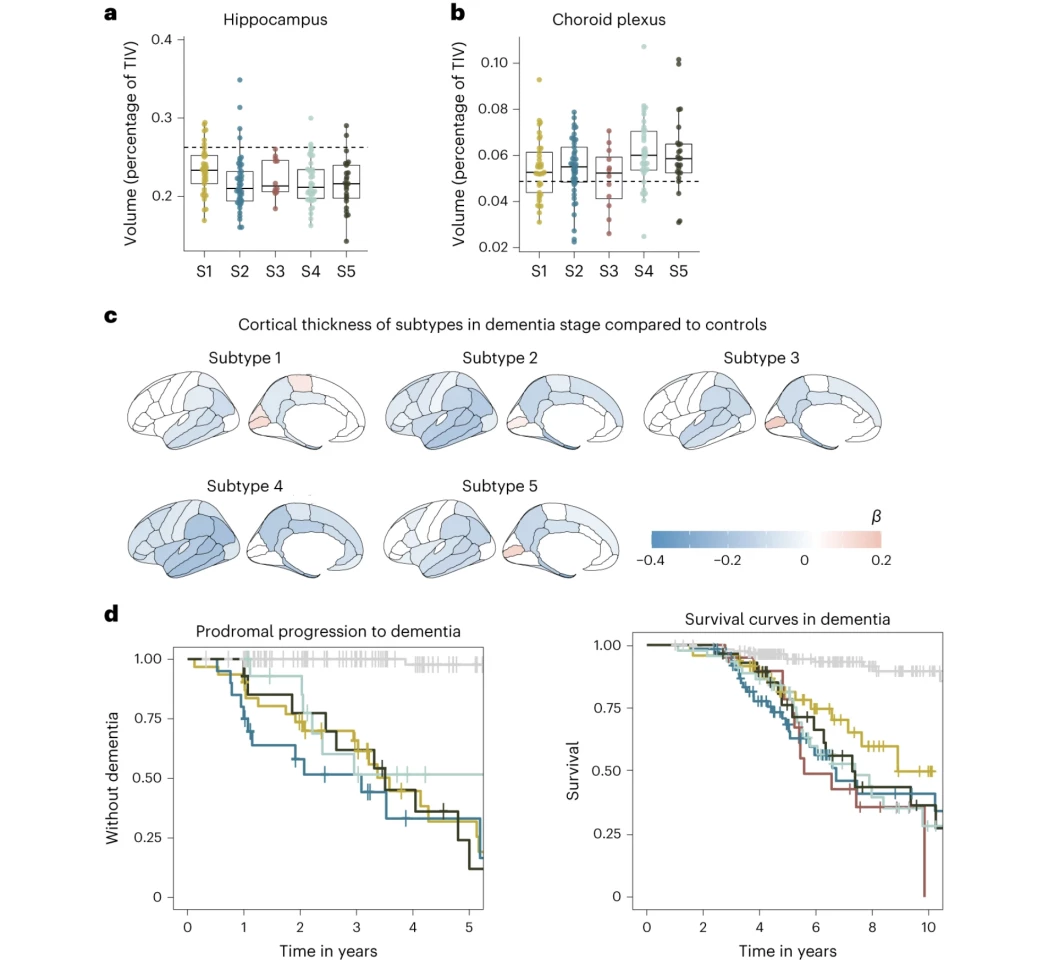

“Each CSF AD subtype reflects specific underlying molecular mechanisms,” the researchers wrote. “The subtypes also differed in cortical atrophy patterns and survival times, underscoring their clinical relevance.”

Those subtypes, identified as subtype 1 through 5, revealed different molecular pathways to what has traditionally been considered one overall disease.

Subtype 1 was linked to neuronal hyperplasticity, or elevated brain cell growth and tau protein levels. The average survival rate was 8.9 years, and the most effective medical approach was antibody treatment.

“Together, our results provide further support for a hyperplasticity subtype in AD, and provide additional insights into the underlying mechanisms, such as that this subtype could be related to a dampened microglial response,” the researchers wrote.

Subtype 2 was associated with innate immune activation, or an overactive immune system, that was marked by the severe brain atrophy and elevated tau levels. It had a mean survival rate of 6.7 years, with the best treatment approach being, not surprisingly, immune suppressants.

Subtype 3, one of the two completely novel variants, was associated with RNA dysregulation, and presented the most rapid decline, with an average survival rate of just 5.6 years. As such, RNA restorative therapeutics might be the most effective treatment path.

“Proteins specifically increased in subtype 3 included heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) and other RNA-binding proteins,” the researchers wrote. “Disruptions in hnRNPs and mRNA have been associated with tau tangles in previous proteomic studies.”

Subtype 4 was linked to dysfunction in the choroid plexus, where CSF is made, and resulted in subdued brain cell growth and blood vessel issues. While both t-tau and p-tau levels appeared normal, this subtype showed the most extreme brain atrophy. The survival rate for this subtype was 7.4 years, and the researchers determined the most effective treatment would be therapeutic inhibition of monocyte infiltration.

“On MRI, subtype 4 had the largest choroid plexus volume,” the researchers said. “Increased choroid plexus volume has been associated with inflammation and structural alterations in AD.”

Finally, subtype 5 was associated with blood-brain barrier dysfunction. The scientists found that people with this AD had impaired blood-brain barrier mechanisms, making them prone to microbleeds and inflammation. The mean survival time for this subtype was 7.3 years and would be best served with cerebrovascular treatments.

“While antibodies may more easily cross the blood–brain barrier in subtype 5, these individuals may be at increased risk for cerebral bleeding that can occur with antibody treatment,” the researchers noted.

As for the subtype split among the tested cohort, 35.5% had subtype 2, 27.9% subtype 1, 17.1% subtype 4, 16.6% subtype 5, and 5.8% subtype 3.

While a fascinating study on its own, the researchers believe it also offers clues as to why the range of treatment options currently available have little success in slowing AD progression, let alone stopping it. They believe comprehensive CSF testing to identify the disease subtype could provide the patient with the most effective treatment in the shortest amount of time.

The research was published in the journal Nature Aging.