Surgery is an indispensable tool when it comes to treating cancer, but those performing the procedures have fine margins to work when cutting away cancerous cells, needing to extract as much as possible while leave healthy tissues intact. University of Pennsylvania scientists have been working on a technique that could offer a helping hand, demonstrating how a glowing dye can be used to light up breast cancer cells in dogs, which they say offers hope for improved surgical outcomes in humans.

The idea of using dyes and particles to light up tumor cells in the human body is one scientists have been exploring for years. This kind of technology could mean that cancers can more safely be removed via surgery, and that doctors can ensure no cells are left to linger and cause the return or spread of the disease.

We have looked at how an oral pill could deliver this type of fluorescent dye to tumors in breast tissue, which then lights up cancer cells under infrared light, and enzymes that can be coated to have a similar effect. The technique the University of Pennsylvania team is investigating centers on an FDA-approved contrast agent called indocyanine green (ICG), which previous studies have shown can allow cancer tissue to be distinguished from healthy tissue under near-infrared light.

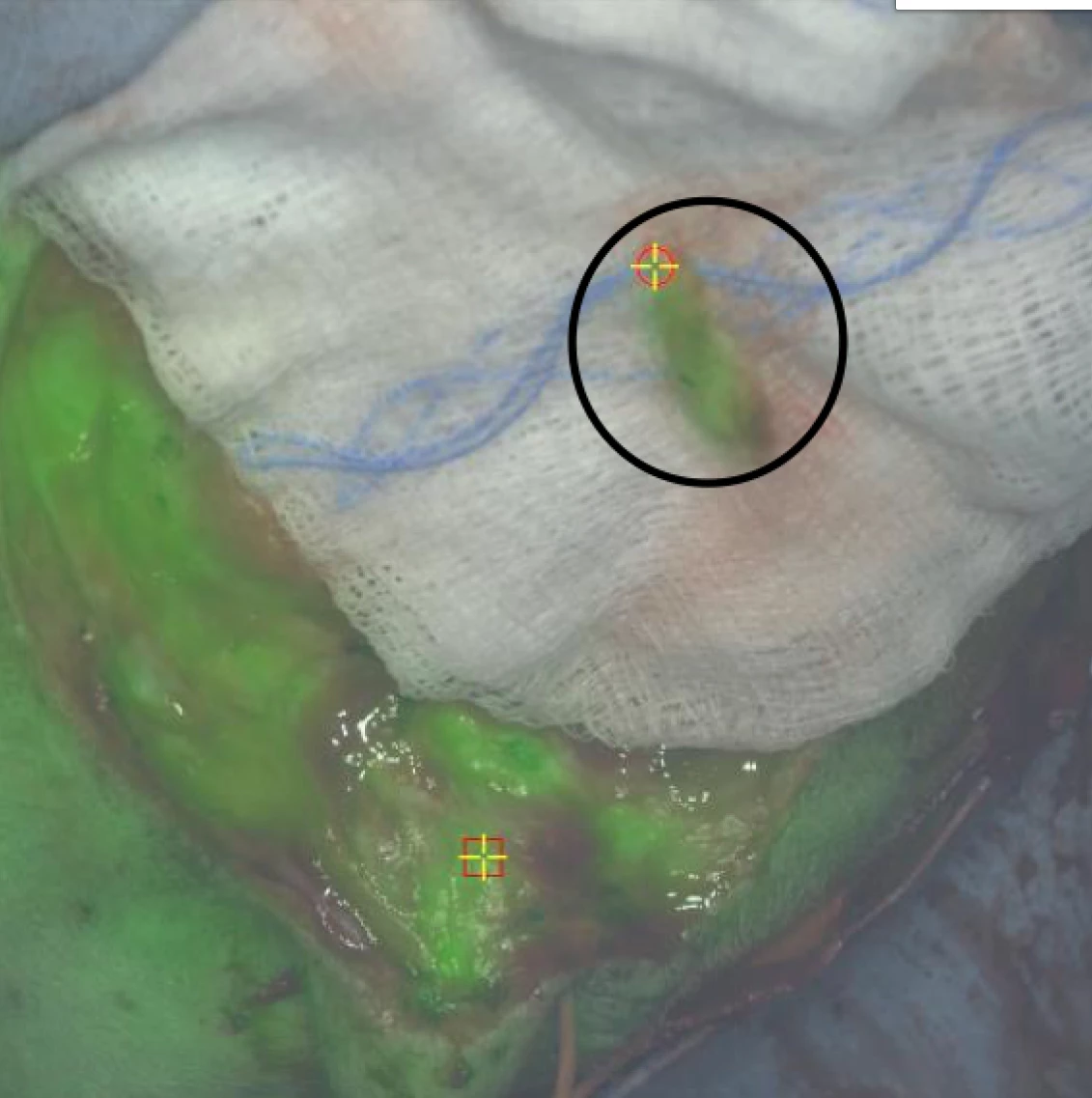

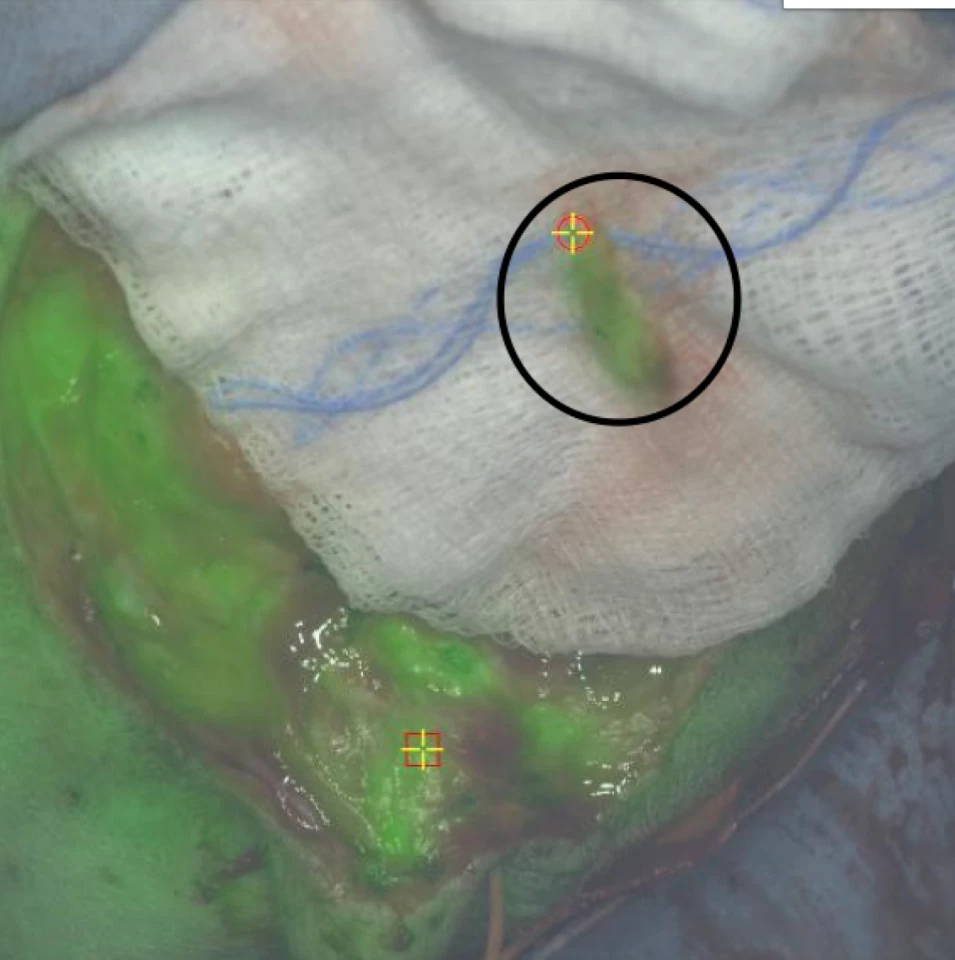

The dye is thought to selectively accumulate in cancer cells because it seeps through the blood vessels in tumors, which are more leaky than regular blood vessels found in healthy tissue. The team set out test the technique in dogs with mammary tumors, which were given an injection of ICG the day before their surgeries.

Following the procedures, the surgeons then inspected the extracted tumors, the original tumor site and the lymph nodes, to see how effectively the ICG illuminates the cancerous cells and whether they may have spread. The team found that the larger tumors did indeed accumulate more dye, and found evidence of cancerous cells in the lymph nodes where fluid from the breast drains to first.

“In women with breast cancer and also in dogs with mammary cancer,” says senior author David Holt says. “it’s prognostic if the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes. What we showed was that we could identify both draining lymph nodes and lymph nodes with metastatic disease.”

The researchers are hopeful that with further work the technique can be adapted to humans, and are now investigating its efficacy in this regard. If nothing else, they say it could bring about improved treatment for our canine friends.

“Doing this kind of research has two main benefits,” says Holt. “The dogs are a great model for human breast cancer, but there are also some real opportunities to benefit the dogs as well.”

The research was published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Source: University of Pennsylvania