It’s a frustrating fact that our bodies can’t regenerate damaged tooth enamel, but scientists at the University of Washington (UW) have now grown mini teeth in the lab that secrete enamel-producing proteins. This could be the first step towards “living fillings” that patch up cavities, or even lab-grown replacement teeth.

Enamel is the hardest tissue in the body, and it coats our teeth to help them endure the stresses of chewing. But over time, they can still suffer from cracks and cavities, and unfortunately this material can’t heal naturally, so fillings or complete removal are often necessary.

For the new study, the UW team investigated how enamel might be repaired, by studying how it’s naturally produced in the first place. The key is a kind of cell called ameloblasts, which make the stuff during tooth development but die off after their job is done.

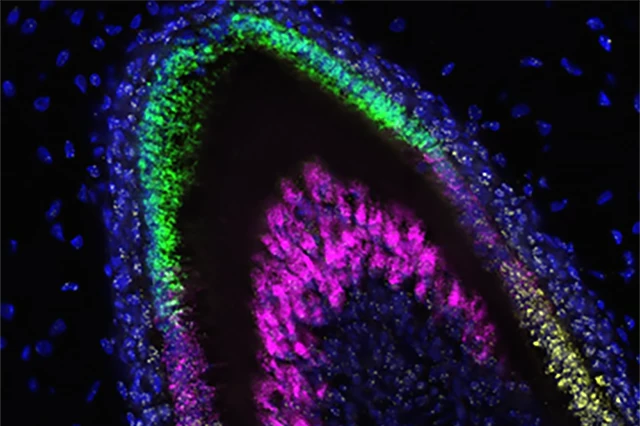

First, the team used a technique called single-cell combinatorial indexing RNA sequencing (sci-RNA-seq), which highlights gene activation throughout a cell’s development. By running this on human tooth cells as they develop, and with the aid of specialized algorithms, the researchers were able to build a blueprint for how ameloblasts form out of stem cells.

Next, they followed their own recipe to try to coax human stem cells to become ameloblasts through a specific sequence of gene activation. And sure enough, with some trial and error the cells arranged themselves into organoids, structures similar to those in developing teeth. They secreted three key proteins – ameloblastin, amelogenin and enamelin – which formed a matrix that mineralized into enamel-like tissue.

“This is a critical first step to our long-term goal to develop stem cell-based treatments to repair damaged teeth and regenerate those that are lost,” said Hai Zhang, co-author of the study.

The team says that with more work to optimize the process, they could even create “living fillings” out of ameloblasts that can be placed into cavities or cracks, and fill them up with newly produced enamel.

The research was published in the journal Developmental Cell.

Source: University of Washington