Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine have tested an experimental new treatment for rheumatoid arthritis in mice. The team implanted stem cells that have been reprogrammed to secrete anti-inflammatory drugs only when they sense inflammation.

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disorder where the immune system mistakenly begins attacking tissue at the joints. Inflammation makes movement of the joints painful and restrictive, causing damage to cartilage and eventually bone. The condition occurs in flare-ups of inflammation, and can be debilitating and hard to treat.

“Doctors often treat patients who have rheumatoid arthritis with injections or infusions of anti-inflammatory biologic drugs, but those drugs can cause significant side effects when delivered long enough and at high enough doses to have beneficial effects,” says Farshid Guilak, senior investigator on the new study.

One of the main problems for these types of drugs is that they don’t stick around in the right spot for long enough to have much of an effect. So for the new study, the Washington University team investigated a way to keep drugs focused on the right spot for longer, by combining two previous technologies.

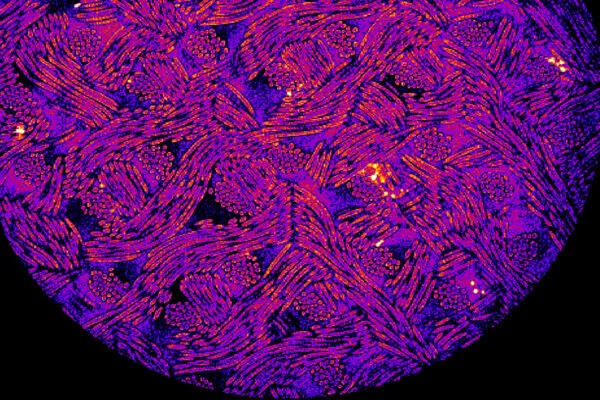

The researchers started with what they call Stem cells Modified for Autonomous Regenerative Therapy (SMART) cartilage cells. Essentially, these are cartilage cells that contain induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that have been engineered so that they can sense inflammation around them and respond by releasing an anti-inflammatory drug. These SMART cartilage cells are then embedded into a scaffolding material that can be implanted into joints.

“The cells sit under the skin or in a joint for months, and when they sense an inflammatory environment, they are programmed to release a biologic drug,” says Guilak.

The team tested the technique in cells in lab culture and in live mice with inflammatory arthritis, with promising results in both. In the mouse tests, the SMART cells significantly reduced the severity of the disease, in terms of joint pain, structural damage and inflammation. But most notably, the treatment completely prevented bone erosion, a severe late-stage symptom.

“We focused on bone erosion because that is a big problem for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, which is not effectively treated by current biologics,” says Yunrak Choi, co-first author of the study. “We used imaging techniques to closely examine bones in the animals, and we found that this approach prevented bone erosion. We’re very excited about this advance, which seems to meet an important unmet clinical need.”

The team says that the technique could eventually replace regular injections of drugs administered to treat rheumatoid arthritis. These drugs fight inflammation by suppressing the immune system, so sustained high doses can lead to a range of negative side effects. Targeting the drugs more precisely at the affected joint, and only when needed, could make the treatment more effective and less invasive.

“Although biologics have revolutionized the treatment of inflammatory arthritis, the continuous administration of these drugs often leads to adverse events, including an increased risk of infection,” says Christine Pham, an author of the study. “The idea of delivering such drugs essentially on demand in response to arthritis flares is extremely attractive to those of us who work with arthritis patients, because the approach could limit the adverse effects that accompany continuous high-dose administration of these drugs.”

Of course, having only been tested in mice, the treatment is still a long way off from any human use, if ever. But it’s an intriguing new approach that could lead to new therapies.

The research was published in the journal Science Advances.