Currently, devices such as pacemakers and deep-brain-stimulating electrodes have to be surgically implanted within patients' bodies. According to a new study, however, such implants may someday be replaced with cells that are activated by ultrasound.

Back in 2015, researchers from California's Salk Institute for Biological Studies showed that when a protein known as TRP-4 was added to neurons in the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, those neurons could be activated with an externally applied burst of ultrasound. Lead scientist Assoc. Prof. Sreekanth Chalasani dubbed the technique "sonogenetics."

Unfortunately, though, it was found that TRP-4 didn't have that effect on the cells of mammals – meaning the technology couldn't be applied to humans.

With that in mind, Chalasani and colleagues set about trying almost 300 separate proteins on a type of human research cell called HEK. They finally discovered that one naturally occurring protein – by the name of TRPA1 – made HEK cells react to ultrasound in the 7-MHz frequency, which is considered safe.

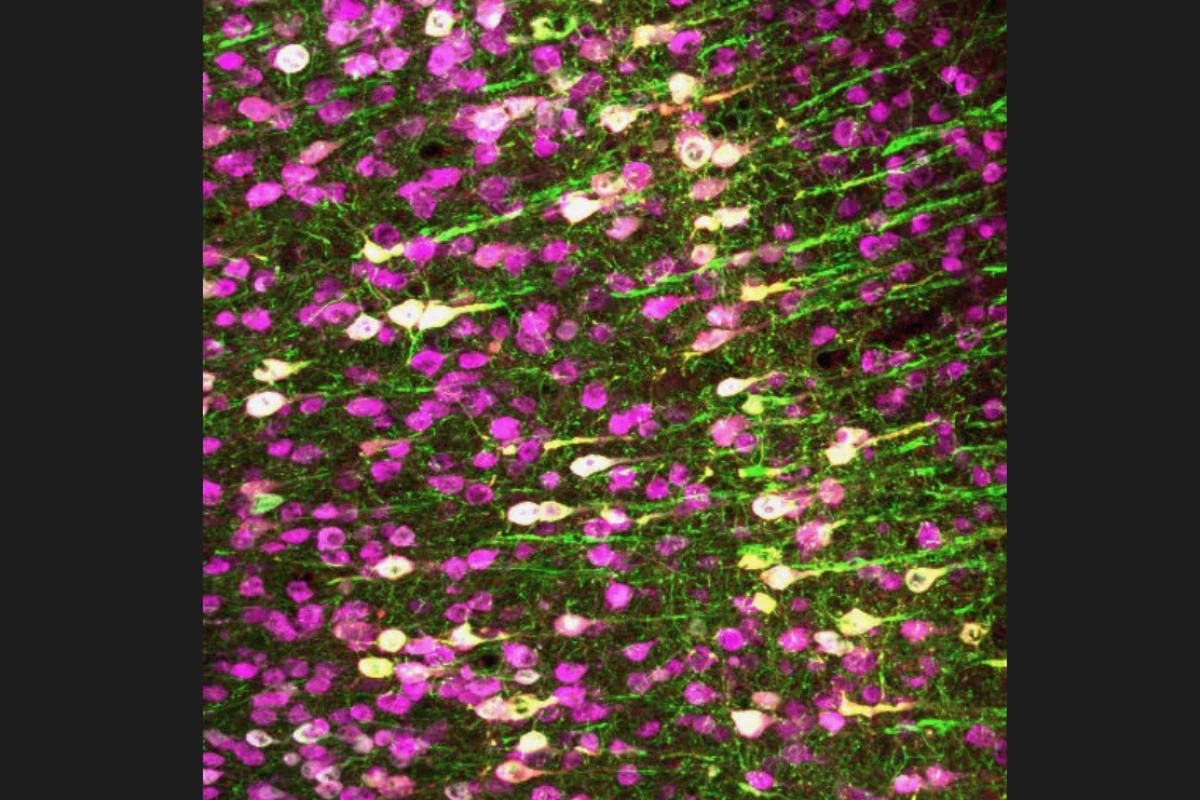

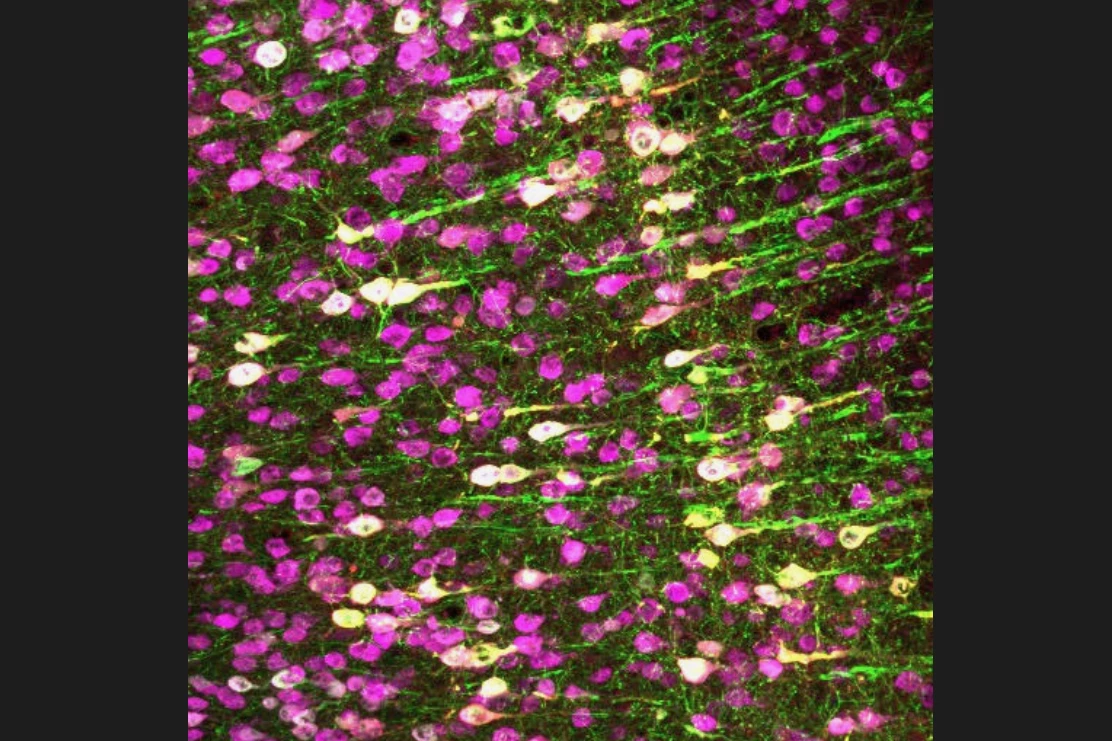

In order to see if the protein worked on other types of mammalian cells, the researchers utilized gene therapy to add the genes for human TRPA1 to a particular group of neurons in the brains of live mice. When those mice were exposed to bursts of ultrasound, the only neurons that were activated were those with the TRPA1 genes.

It is now hoped that eventually, TRPA1 genes could be added to cells in human patients' hearts and brains (among other places). When activated by an external ultrasound-emitting device, those cells could serve the same purpose as pacemakers or the brain-implanted electrodes that are currently used to treat conditions such as epilepsy and Parkinson's disease.

The scientists are now investigating the precise manner in which TRPA1 senses ultrasound, with an eye towards tweaking the protein to enhance its sensitivity. They are also looking for proteins that deactivate cells in response to ultrasound.

A paper on the research was recently published in the journal Nature Communications.