History is littered with anecdotal evidence of the relationship between stress and graying hair, from Marie Antionette's overnight transformation following her capture, to US presidents taking on more salt than pepper during their tenure. A new study has produced first-of-a-kind scientific evidence of this connection, identifying proteins in human hairs that seem to drive this process, while also demonstrating how it might even be reversed.

The study was carried out by scientists at Columbia University who took aim at what they see as a gap in this type of research so far. While psychological stress has long been seen as a driver of graying hair, it has been difficult for scientists to connect the dots, as correlating hair pigmentation with times of individual stress is a tricky undertaking.

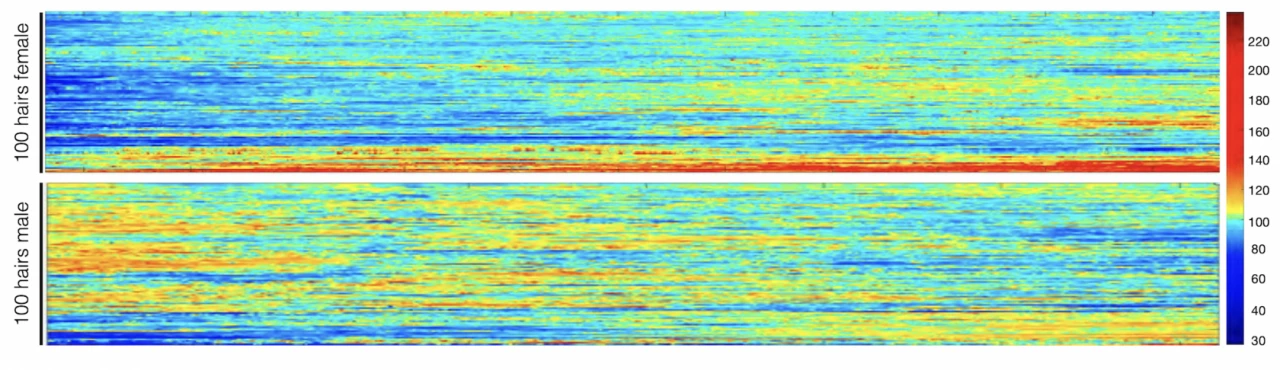

As a solution to this, the scientists enlisted 14 volunteers who kept "stress diaries," in which they reviewed their calendars and rated weeks by levels of stress. These subjects then supplied the scientists with hair samples, which the scientists split into tiny slices and analyzed to map the degree of graying. Each slice, measuring around a twentieth of a millimeter wide, represented about an hour of hair growth, and provided a quantifiable physical timescale of the graying process.

“If you use your eyes to look at a hair, it will seem like it’s the same color throughout unless there is a major transition,” says Ayelet Rosenberg, first author on the study. “Under a high-resolution scanner, you see small, subtle variations in color, and that’s what we’re measuring.”

Comparing these variations to the stress diaries provided some interesting insights. Not only were "striking associations" between stress and hair graying found, but in some cases a reversal of that graying as the individual's stress was alleviated was also seen. Gray hairs returning to their natural color is something that has never been quantitatively documented, according to the researchers.

“There was one individual who went on vacation, and five hairs on that person’s head reverted back to dark during the vacation, synchronized in time,” Picard says.

Digging further into the details, the team measured levels of thousands of different proteins over the length of the hair and were able to identify changes in 300 of them as the hair turned gray. Using a mathematical model, the team tied these alterations to stress-induced changes in the mitochondria.

“We often hear that the mitochondria are the powerhouses of the cell, but that’s not the only role they play,” Picard says. “Mitochondria are actually like little antennas inside the cell that respond to a number of different signals, including psychological stress.”

The role of mitochondria in linking stress and hair color is what separates this study from others exploring the phenomenon. A notable one published by Harvard researchers in 2020, for example, demonstrated in mice that acute stress can cause the permanent deletion of pigment-producing stem cells in hair follicles.

“Our data show that graying is reversible in people, which implicates a different mechanism,” says co-author of the new study, Ralf Paus. “Mice have very different hair follicle biology, and this may be an instance where findings in mice don’t translate well to people.”

The study certainly raises some interesting questions around stress and graying hair, and how lifestyle changes could affect the process. While avoiding stress is good for our health in all sorts of ways, the scientists emphasize that it will have limitations when it comes to keeping our hair youthful and full of color.

“Based on our mathematical modeling, we think hair needs to reach a threshold before it turns gray,” Picard says. “In middle age, when the hair is near that threshold because of biological age and other factors, stress will push it over the threshold and it transitions to gray. But we don’t think that reducing stress in a 70-year-old who’s been gray for years will darken their hair or increasing stress in a 10-year-old will be enough to tip their hair over the gray threshold.”

The research was published in the journal eLife, while the video below offers a look at the team's observations.

Source: Columbia University