Scientists working towards next-generation treatments for blindness have made an exciting breakthrough, demonstrating how a new method of injecting healthy cells into the eyes could act as a one-two punch to address vision loss. The technique, demonstrated in mice, explores how a singular treatment can be used to target the death of two cell types in the eye, with the team hopeful of one day using this approach to treat forms of blindness that are currently incurable.

The work was carried out by scientists studying engineered biomaterials at the University of Toronto (UT). The team has spent a number of years investigating treatments for conditions like age-related macular degeneration (AMD), one of the leading causes of blindness, and the rarer retinitis pigmentosa. Both conditions are characterized by the death of cells at the back of the eye.

More specifically, these conditions see the deterioration of the photoreceptor cells and another type known as retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) cells. Efforts to address this have involved injecting healthy versions of either into the eye to replace the dead cells, though most don’t survive for long in their new environment. But because the survival and wellbeing of these cell types are closely intertwined, the UT team has been exploring how targeting both at the same time might lead to better results.

“RPE and photoreceptors are considered as one functional unit – if one cell type dies, then the other one will too,” says study author Professor Molly Shoichet. “We wondered if co-delivery of both cell types would have a bigger impact on vision restoration.”

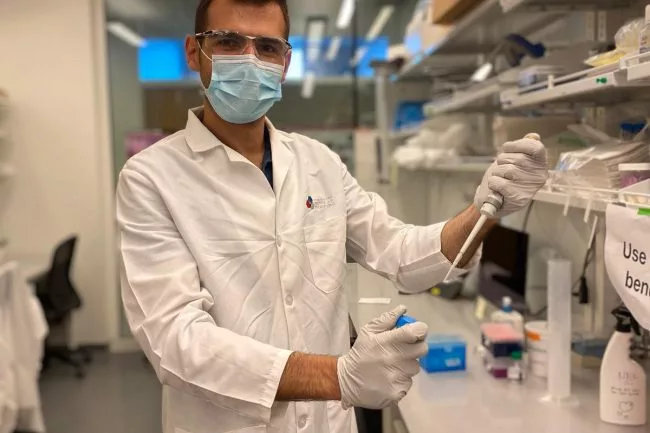

The breakthrough comes courtesy of a new form of a hydrogel, a biomaterial that the team has been investigating for a number of years with mixed results. Loading up hydrogels with photoreceptor cells and injecting them this way had brought some vision improvements in mouse studies before, but the scientists have now come up with a recipe that allows the RPE cells to go along for the ride.

“Our hydrogel is viscous enough to ensure a good distribution of both cell types in the syringe, yet it also has important shear-thinning properties to facilitate injection through the very fine needle required for this operation,” says Shoichet. “The combination of these properties opened up a new strategy for successful delivery of multiple cells.”

Testing out this dual-injection method on mouse models of AMD, the team found that the rodents regained around 10 percent of their normal vision acuity, compared to mice who received just one of the two cell types and showed little to no improvements. In behavioral experiments, these mice were also more active in dark chambers.

“We designed the experiment so that I wouldn’t know which mice had received the treatment and which received a placebo,” says lead author Nick Mitrousis. “When some of the mice started responding, I kept vacillating between optimism that the experiment might have actually worked, and worry that the recovering mice might just be split between the different treatment groups.”

The behavioral changes did turn out to be a result of the co-injection treatment, which has the researchers excited, but with cautious optimism. No other experiment has attempted to combine these two cell types into the one treatment so the early findings are indeed significant and promising, though the team is conscious of the long road ahead and the many hurdles still to overcome.

“First, we need to demonstrate the benefit of this strategy in multiple animal models,” says Shoichet. “We’ll also need a source of human photoreceptor cells and a way to further improve cell survival, both of which we’re working on. Still, we are very excited by these data and always open to collaboration to take the research further.”

The research was published in the journal Biomaterials.

Source: University of Toronto