A group of Texas-based researchers has developed an effective way to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that involves zapping the vagus nerve around the neck, using a device the size of a shirt button.

This new method could provide a glimmer of hope for the millions of people around the world who suffer from PTSD – and that includes a much wider gamut of patients beyond military veterans who have faced combat.

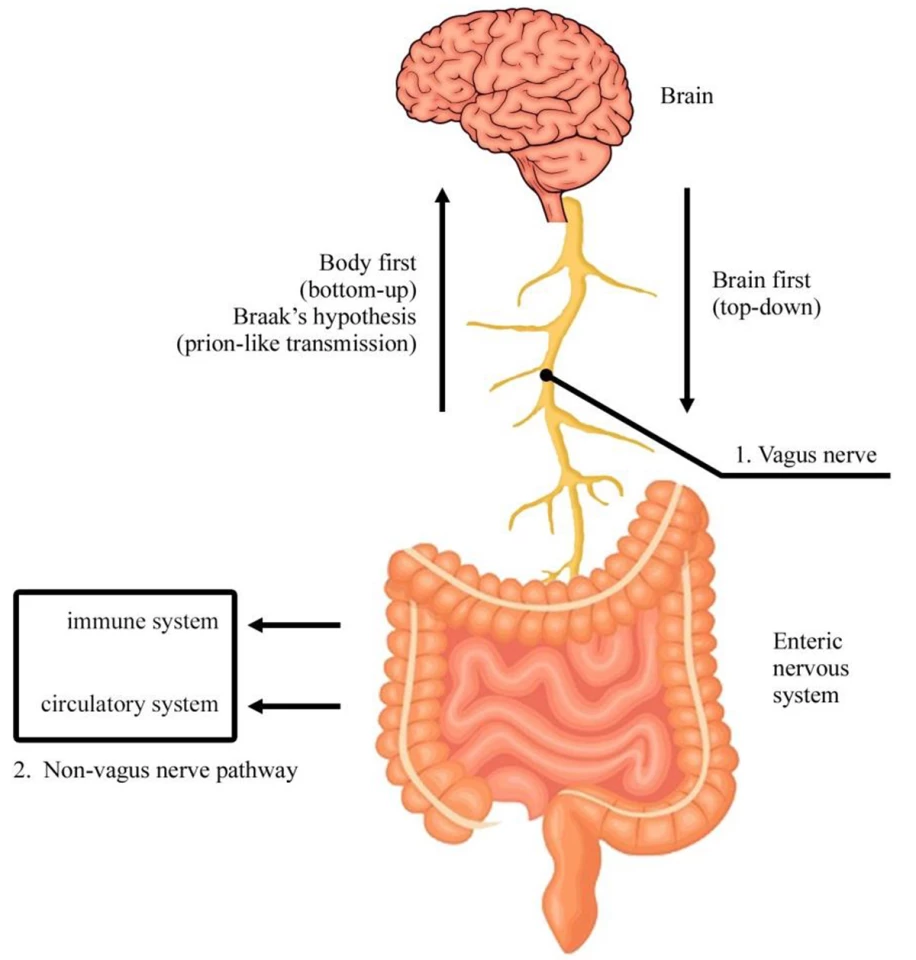

Let's get a sense of what the researchers are working with here. The vagus nerve is the main nerve of your parasympathetic nervous system, which controls key involuntary body functions like your heart rate, digestion, immune system, and even your mood.

This is also the the largest parasympathetic nerve in the body, and it runs from the brain to the large intestine. There are left and right vagal nerves that join to form the vagal trunk. Stimulating these nerves with electrical impulses can help treat epilepsy and depression, and could also help address conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and PTSD.

This new treatment works in tandem with a traditional PTSD treatment called prolonged exposure therapy (PET), where patients gradually confront the memories and situations they've been struggling with, in a controlled and safe environment.

The research team, which includes scientists at The University of Texas at Dallas and Baylor University Medical Center, combined PET with the delivery of short bursts of stimulation of the vagus nerve through a small device fitted to a participant’s neck.

The researchers conducted a Phase 1 trial with nine patients over 12 vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) sessions. In assessing the participants four times over the course of six months after the therapy had concluded, they found that all the patients were symptom-free.

"In a trial like this, some subjects usually do get better, but rarely do they lose their PTSD diagnosis," said Dr. Michael Kilgard, a neuroscience professor at UT Dallas and an author of the paper that appeared in the journal Brain Stimulation in March. "Typically, the majority will have this diagnosis for the rest of their lives. In this case, we had 100% loss of diagnosis. It’s very promising.”

VNS is thought to enhance synaptic plasticity, which refers to the brain's ability to change and adapt at the level of its neural connections. PET shows the brain what connections need to change (those involved in the fear response to trauma memories). Meanwhile, VNS provides a chemical 'boost' (through neuromodulators, or chemical messengers that can influence neural activity, like acetylcholine and norepinephrine) that makes the brain's wiring more capable of changing during that specific time.

This enhancement of plasticity is thought to make the extinction of fear stronger and more lasting, leading to the observed reductions in PTSD symptoms.

The concept of using VNS isn't entirely new: more that a decade ago, it had been shown to effectively aid in treating movement impairment in people who've suffered a stroke, and more recently in reducing fatigue in sleep-deprived subjects.

Beyond finding a way to apply it in conjunction with PET, the researchers also developed a tiny dime-sized implantable VNS device to deliver bursts of stimulation, which could make it far easier to deliver treatment.

This new method joins the list of numerous innovative approaches to treating PTSD from recent years, including the use of psychedelic drugs, short bursts of exercise, mindfulness programs, and even the video game Tetris.

The Texas team's already on its next move: a more comprehensive Phase 2 pilot study with participants in Dallas and Austin. The researchers hope this could one day serve as an option "for people who don’t get better with cognitive behavioral therapy alone.”

Source: UT Dallas