We've seen drugs capable of turning white fat-storing tissue into brown, fat-burning tissue, but a new nanoparticle delivery system could significantly improve how such treatments are delivered, avoiding unwanted side effects. The work was conducted by a team from MIT and Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Obesity is a huge health issue, with almost a third of people in the US falling into the bracket. It's also the root cause of some 20 percent of cancer deaths in the country, making it more dangerous than smoking in that regard.

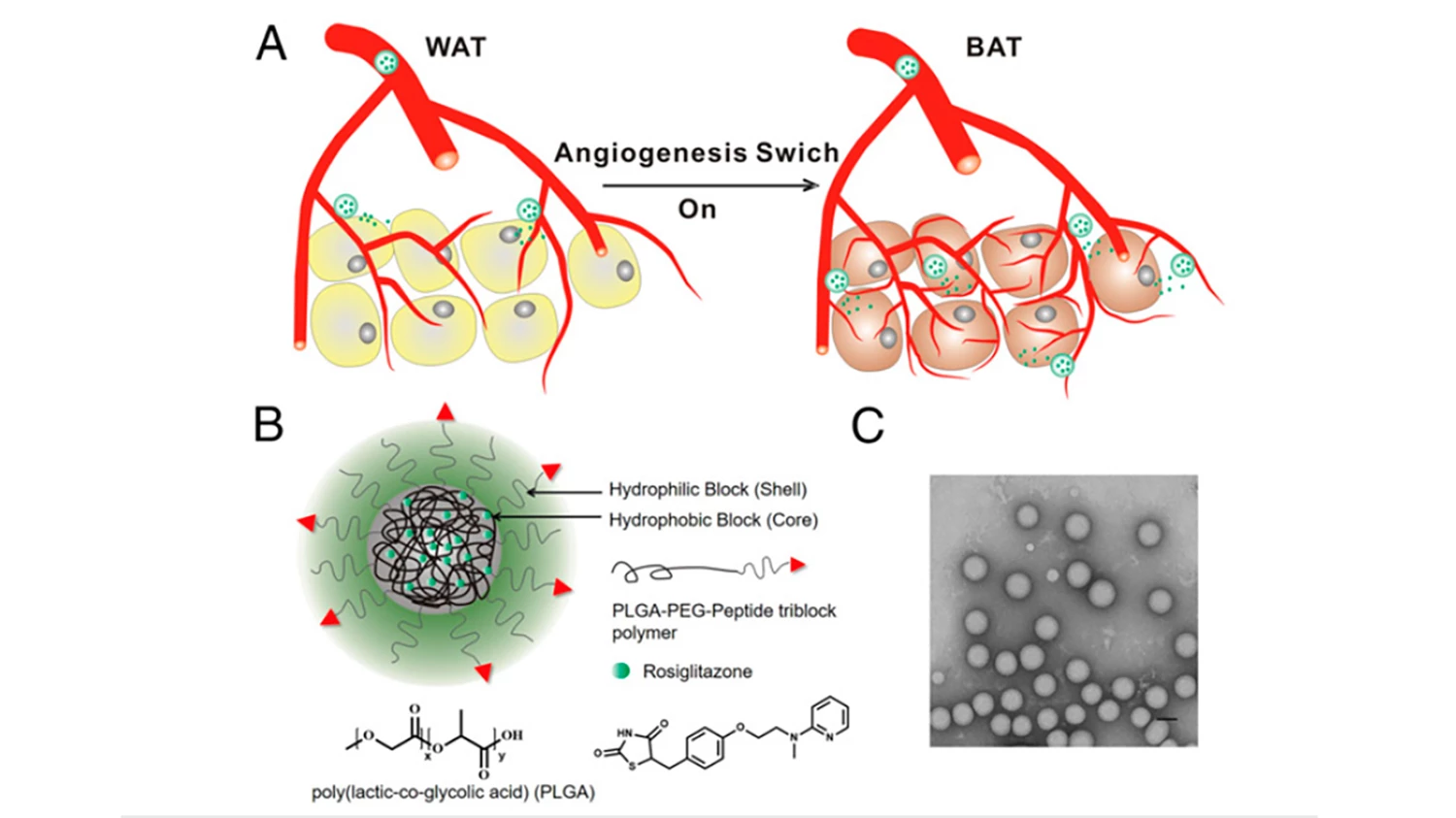

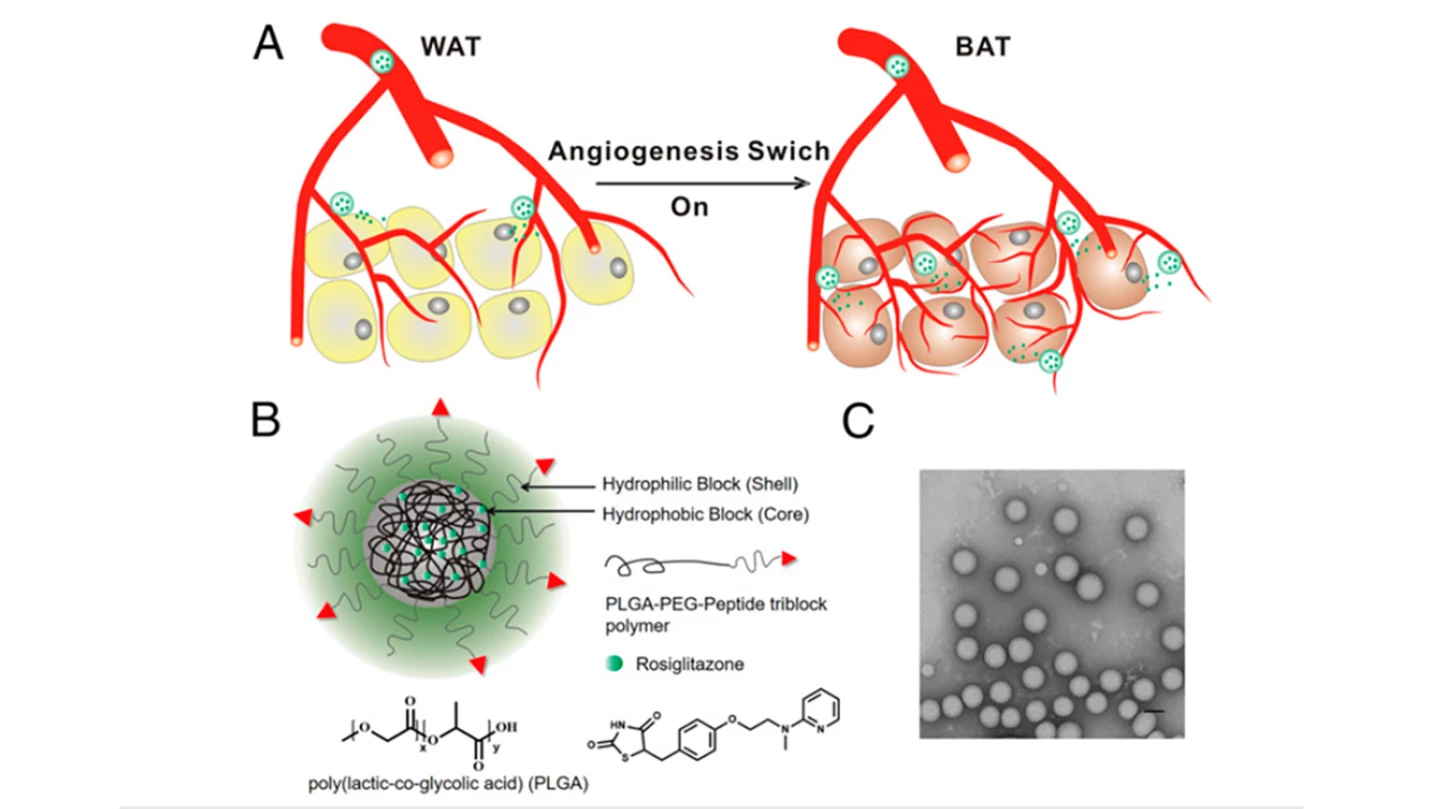

Previous research with laboratory mice has shown that encouraging the growth of new blood vessels helps white adipose tissue, which stores fat, switch to brown adipose tissue, which burns it instead. Unfortunately, that same treatment can lead to side effects, causing harm elsewhere in the body.

In an effort to improve things, the MIT and Brigham and Women's Hospital researchers looked to a nanoparticle delivery system. The idea is to provide more targeted delivery of the drug, thereby minimizing its effects in other parts of the body.

The particles carry the drugs in hydrophobic cores made from a polymer called PLGA. Two drugs were tested – one designed to tackle diabetes, called rosiglitazone, and a hormone treatment called prostaglandin. Both drugs activate a cellular receptor called PPAR, stimulating the growth of new blood vessels, and therefore triggering the transformation of adipose.

A targeting molecule was embedded into the outer core of the nanoparticles, itself made from a polymer called PER. The targeting molecule is designed to guide the particle to the fat burning site, binding with proteins in the lining of the blood vessels surrounding adipose tissue.

The nanoparticles were found to be effective in testing on obese laboratory mice, where the treatment dropped the animals' body weight by 10 percent and significantly reduced their cholesterol levels. The subjects also became more sensitive to insulin, which is an area where obesity often has a pronounced negative effect, heightening diabetes risk.

The treatment was delivered to the mice once every two days for 25 days, and no negative side effects were observed.

For the study, the treatment was delivered via injections, but the researchers hope to one day be able to administer it through oral pills. With that goal in mind, the team is currently exploring reliable mechanisms by which the nanoparticles could penetrate the lining of the intestines. Even with that challenge left to overcome, the work is still extremely promising.

"The advantage here is now you have a way of targeting [the drugs] to a particular area and not giving the body systemic effects," said MIT's Professor Robert Langer. "You can get the positive effects that you'd want in terms of anti-obesity but not the negative ones that sometimes occur."

The findings of the study are published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Source: MIT