How did a guitar that failed to grab its intended market – the market it was literally named after – end up becoming the instrument of choice across surf-rock, post-punk, new wave, power pop, shoegaze and more?

If my house was on fire, and my wife and kids were okay, and I was told I could take only one material possession with me, I wouldn’t hesitate. Well, okay, I guess my laptop would tempt me because I have a hell of a lot of my life on there. But putting that aside, I’d immediately grab my Fender Jazzmaster.

It’s neither vintage nor very valuable in monetary terms. It’s a sunburst 2012 model and it’s MIM (Made In Mexico). I bought it in the Lower East Side of New York in that long-ago, seemingly mythical time when the Australian dollar was at parity with the US dollar. It set me back the princely sum of $700.

I’ve bought other guitars since then, but I only ever play this one live, in two different bands, and if I was pushed due to dire economic circumstances, I would sell all the others and just keep this one. It will go with me to my grave.

Why? Well, that’s what this story is about.

I mainly play indie rock, new wave, post-punk and power pop, and this guitar does exactly what I want it to do when pushed through my Vox AC15. It stays in tune even if dropped down a flight of stairs – not that I’ve ever literally done that, but it’s taken knocks and always stays tried and true. It sounds jangly when I want it to and biting when I want it to. It takes off when I kick my Rat pedal.

And it just looks so damn cool. Whenever I strap it on, I feel 50 percent sexier. As you can see from my photos, I need all the help I can get in that department.

I first fell in love with Jazzmasters at exactly the same time I fell in love with Elvis Costello. There he was on the back cover of his 1977 debut album My Aim Is True, a dweeb who looked as nerdy as me, knock-kneed and clutching a cool, unusually shaped guitar I’d never seen before.

After hearing that album for the first time, I wanted to be Elvis Costello. So, naturally, I needed to play that same guitar. After doing some research, I discovered that it had a strange history.

Fender introduced the Jazzmaster in 1958, and, as the name suggests, marketed it towards jazz guitarists.

In that respect it was an abject failure. Suspicious of this solid-bodied, space-age looking instrument, with its bonus array of bewildering switches and dials, the jazz cats turned up their noses and stayed away in droves, preferring to stick with their hollow, big-bodied archtops.

But soon, a completely different set of musicians embraced the guitar – a clutch of 1960s surf rock bands such as The Ventures and The Surfaris loved the brightness, twang and jangle they could coax from a Jazzmaster, and the instrument soon became strongly associated with surf music.

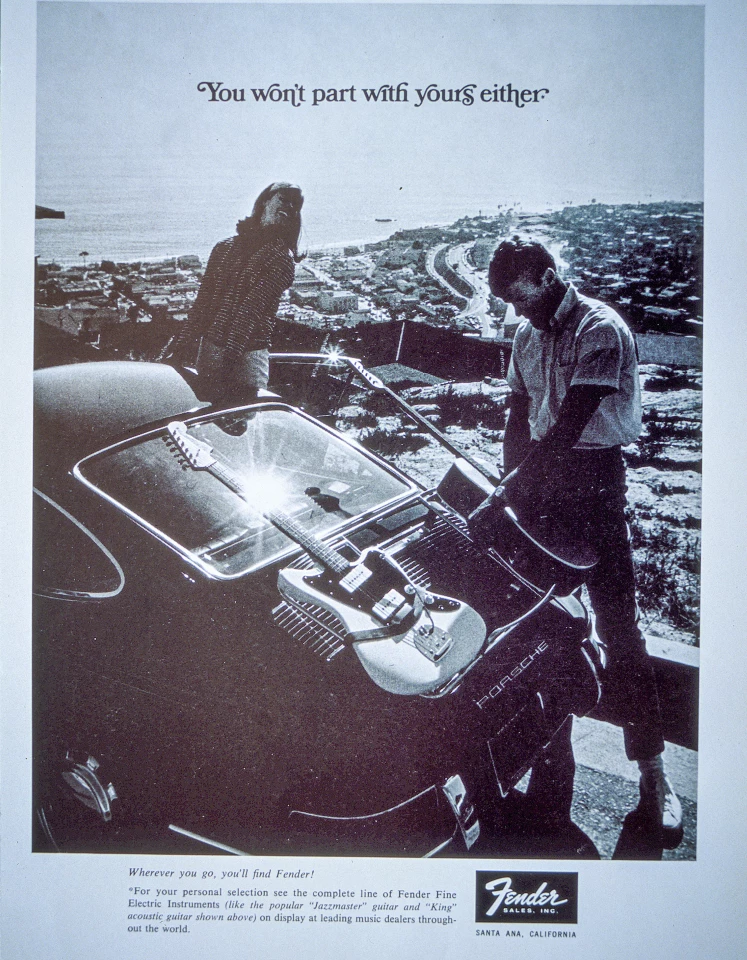

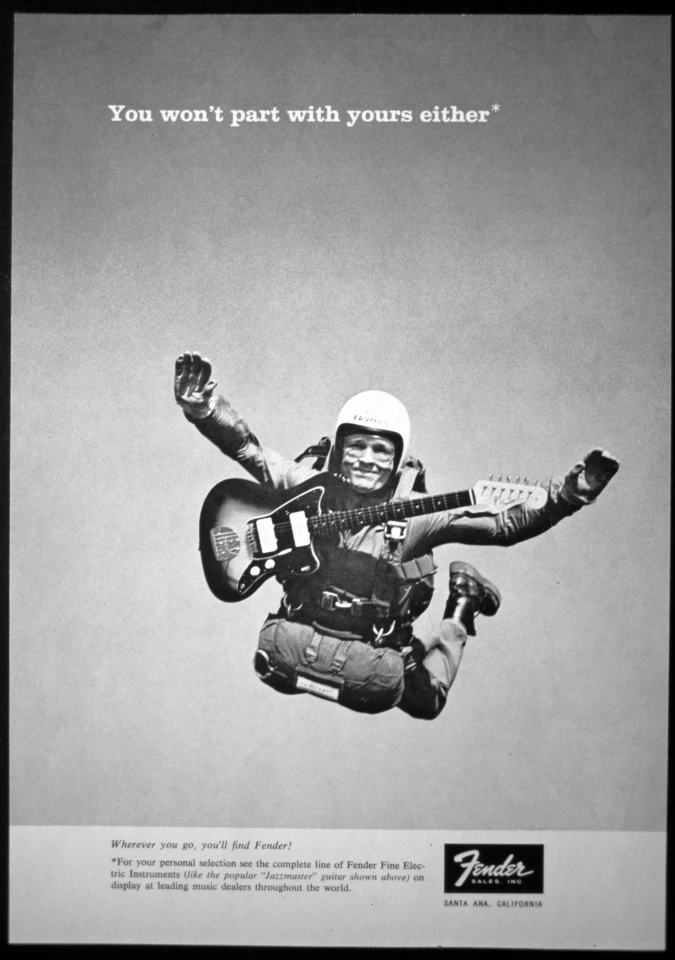

Fender reacted accordingly. If you look at vintage advertisements for their offset range, they’re often featured in a beach setting, in the great outdoors and in adventurous situations – two of the more memorable ones show a guy strumming a Jaguar while riding a wave on a longboard, and a bloke who has just jumped out of a plane, with a parachute on his back and a Jazzmaster around his neck (I can vouch for the durability of the Jazzmaster, but please don’t try this at home, people).

The slogan for many of these ads was “You won’t part with yours either.” Jazzmaster-heads like myself will agree that this piece of copywriting turned out to be a prophecy.

The Jazzmaster was very different to Fender’s other iconic models, the Telecaster and Stratocaster. It had an offset body that gave it an angular, futuristic look, two separate circuits for lead or rhythm playing, a floating tremolo, and unique “soap-bar” single coil pick-ups.

Despite surf-rock guitarists taking up the Jazzmaster in the ’60s, by the ’70s they were seen as out-dated and out of step with the prevailing rock scene, as budding guitar heroes went straight to the Fender Stratocaster or Gibson Les Paul. In fact, Fender stopped producing them altogether in 1980 due to declining sales (Fender Japan would re-introduce them six years later).

Subsequently, unloved second-hand Jazzmasters could be picked up cheaply in pawn shops and junk stores. And that’s how they fell into the hands of power-pop, post-punk, new wave, and, eventually, alternative rock musicians who couldn’t afford more expensive instruments.

Apart from Costello, one of the most famous proponents of the Jazzmaster in the ’70s was Tom Verlaine of Television, whose ground-breaking, jagged, spidery playing style came to be associated with the guitar.

In the ’80s, Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo of Sonic Youth started buying them and they went even further, cranking them, flailing at them, and making them wail and roar by doing things like jamming screwdrivers and drumsticks under the strings, creating the foundation for alternative rock.

The number of musical styles the Jazzmaster helped foster continued to expand across the decades. Robert Smith of The Cure made his Jazzmaster sound both nervy and gothic. J Mascis of Dinosaur Jr made his sound like a hurricane, and Fender eventually brought out a popular Mascis signature Jazzmaster through their Squier brand.

And Kevin Shields of My Bloody Valentine pretty much reinvented what a Jazzmaster could sound like, building massive walls of loud, woozy, shuddering feedback. That blurry photo on the cover of the band’s seminal 1991 album Loveless is of a Jazzmaster.

From Pops Staples in The Staple Singers through to Nels Cline of Wilco, the Jazzmaster has morphed over the years as far as what it can do in a musical context, while keeping the same iconic shape and basic functions.

Since 1958, Fender has refined and updated aspects of the instrument. The latest incarnation was previewed in October at Fender Experience 2025 in Tokyo, when the American Professional Classic Series was launched.

The new Jazzmaster in this series, which retails for $US1599.99, includes many of the updates featured across the series, including overwound Coastline pickups, a modern C-shape neck, and all-new colour shades featuring a faded vintage look.

But the biggest change is causing some chatter. The latest iteration does away with the rhythm circuit. For the uninitiated, that’s the switch and two thumbwheels on the upper edge of the face of the guitar, which was initially designed to put the “jazz” in Jazzmaster, providing a darker, smokier tone that cut down the highs.

Anyone who has been on a Jazzmaster online forum of late will see some disparaging comments. A couple of the more emotive ones include: “The rhythm circuit is sacred and it’s blasphemous to remove it” and “For me, a Jazzmaster without a rhythm circuit is

half a Jazzmaster.”

I’m in two minds on this one. To be perfectly frank, I never use the rhythm circuit on my Jazzmaster anyway. I’m no jazz guitarist and I find no need for that tone. I want my guitar to sound bright, with plenty of jangle and crunch. In fact, very occasionally I hit the rhythm circuit switch by mistake, changing the sound of my guitar mid-song, which immediately engages my “swearing switch”.

I know other Jazzmaster players who either tape the rhythm circuit switch in the off position, or cut off the small eraser from the end of a pencil and jam it into the space to prevent the switch from moving.

But on the other hand, I really love the look of those switches and thumbwheels because they’re such an integral part of the guitar’s vintage appearance.

While attending Fender Experience 2025 in Tokyo, I brought this up with Patrick Harberd, Fender’s Senior Product Development Manager.

“Of course, I’m more than aware there’s been online chatter about getting rid of the rhythm circuit in the new Jazzmaster,” he said. “You play a Jazzmaster, so you know that they have a lot of idiosyncrasies compared to other Fender guitars, and people have strong opinions about them.

“We decided not to include the rhythm circuit to simplify the instrument, because this series is about making guitars that are reliable and as easy as possible to play, whether you’re buying your first guitar, or you’re a working musician.

“With that said, the new Jazzmasters are routed underneath to take the rhythm circuit, so if you later decide you want to mod your guitar, it’s very easy to take that path further down the track.”

Despite these changes, some things stay the same, and always will. Whenever I see a Jazzmaster, whether it’s a new version, a beautiful 1960s vintage instrument I can’t afford, or my beloved MIM Jazzmaster when I take it out of its case to play a gig, it takes me back to seeing that picture of Elvis Costello on the cover of My Aim Is True, my eyes widening and a younger me saying to myself: “I’ve got to have one of those!”

And I’m so glad that I do.

Source: Fender

Note: New Atlas may earn commission on purchases made through links.