Alan C. Short, a professor of architecture at the University of Cambridge, has just released a book entitled "The Recovery of Natural Environments in Architecture: "Air, Comfort and Climate" in which he says that current building practices have become energy inefficient by sealing us off from the world around us. Instead of blocking out these natural forces and relying on mechanical systems to control our indoor environments, Short says that we should harness them to naturally heat, cool and promote airflow in our structures.

We got with professor Short as part of our One Big Question (OBQ) series and asked him: How could we better today's buildings by looking to the past?

Here's what he had to say.

Modern buildings are denatured compared to their predecessors designed before the era of universal air-conditioning, of "artificial weather." There is now a fetish for super lightweight glass building envelopes with no resilience to the climate outside, incapable of sustaining a habitable environment inside without the gas-guzzling life-support infrastructure provided by air conditioning. And it really is gas-guzzling.

Buildings in a Westernized economy account for between 40 and 50 percent of electrical energy use, with some 30 percent in China, much of it consumed through artificial cooling. This is not a necessary prerequisite of a civilized modern society. Quite the reverse. To challenge this unsustainable practice it makes a lot of sense to look back at how designers made large public buildings comfortable before the era of air conditioning.

Through the nineteenth century, the public building types with which we are so familiar were invented in order from national parliamentary buildings to government ministries, law courts, theaters and opera houses, gathering places for the new nonconformist religions, and most particularly, hospitals. What emerges is a completely forgotten art and science of making naturally ventilated and passively cooled buildings in which the very architecture of the buildings was configured to drive air through at the rates required to deliver health and well-being, sometimes at a huge scale.

Until the 1870s designers and their clients were anxious to flush out miasmas, toxic malodorous vapors emanating from the soil at night thought to spread disease. As germ theory became more commonly accepted it emerged that the same design innovations to flush away miasmas would expel airborne pathogens. From the Inman Report on the foul state of the House of Commons and the peers' chamber of the mid 1830s leading to the ventilation theory and practice of Dr. James Boswell Reid, to the more sophisticated designs of General Morin in France, to the authentically scientific propositions of Surgeon Major Billings in the USA of the 1880s, nineteenth century and early twentieth century buildings became more and more sophisticated. Hospital designers were at the forefront of the innovations to suppress cross infection between patients.

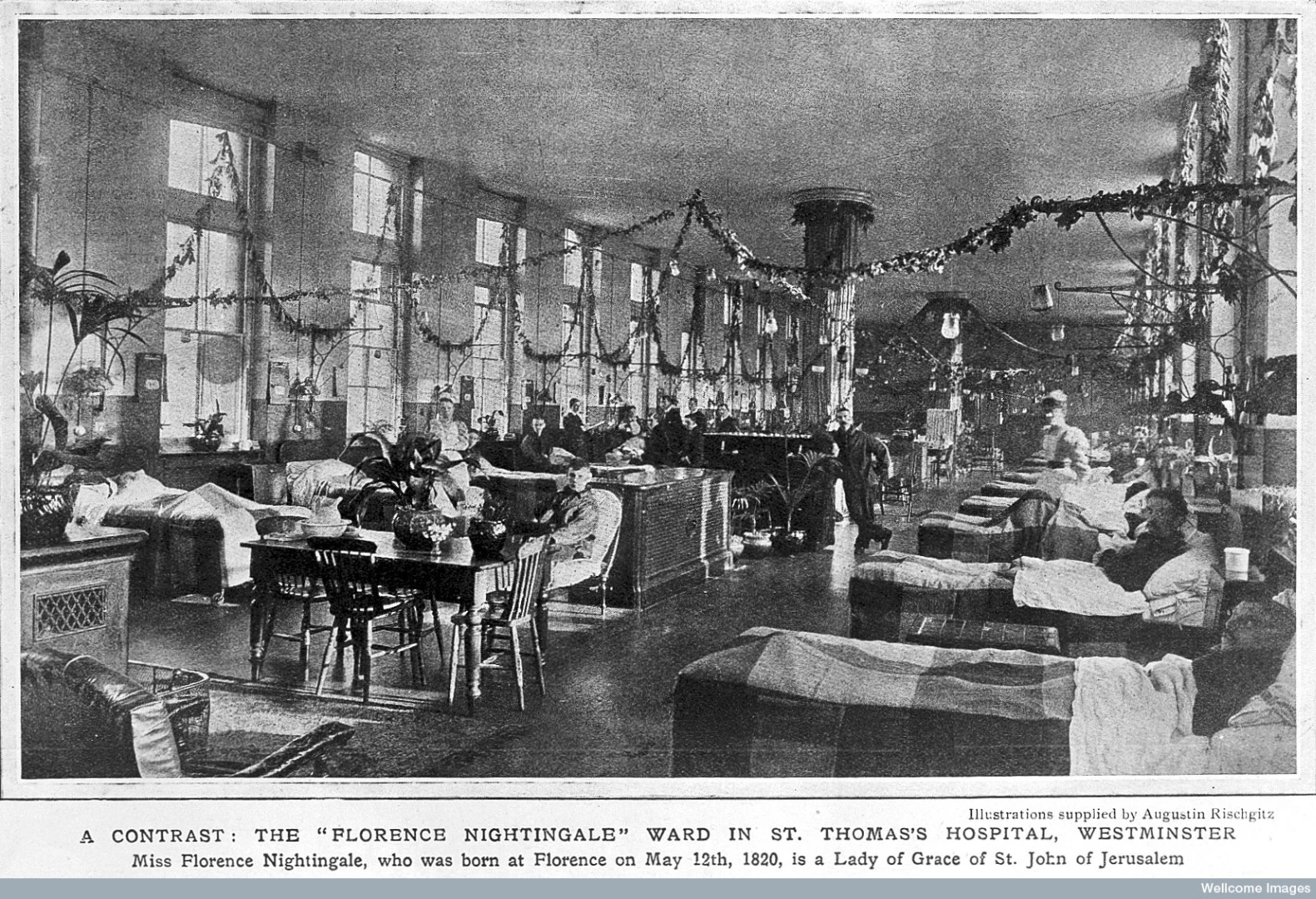

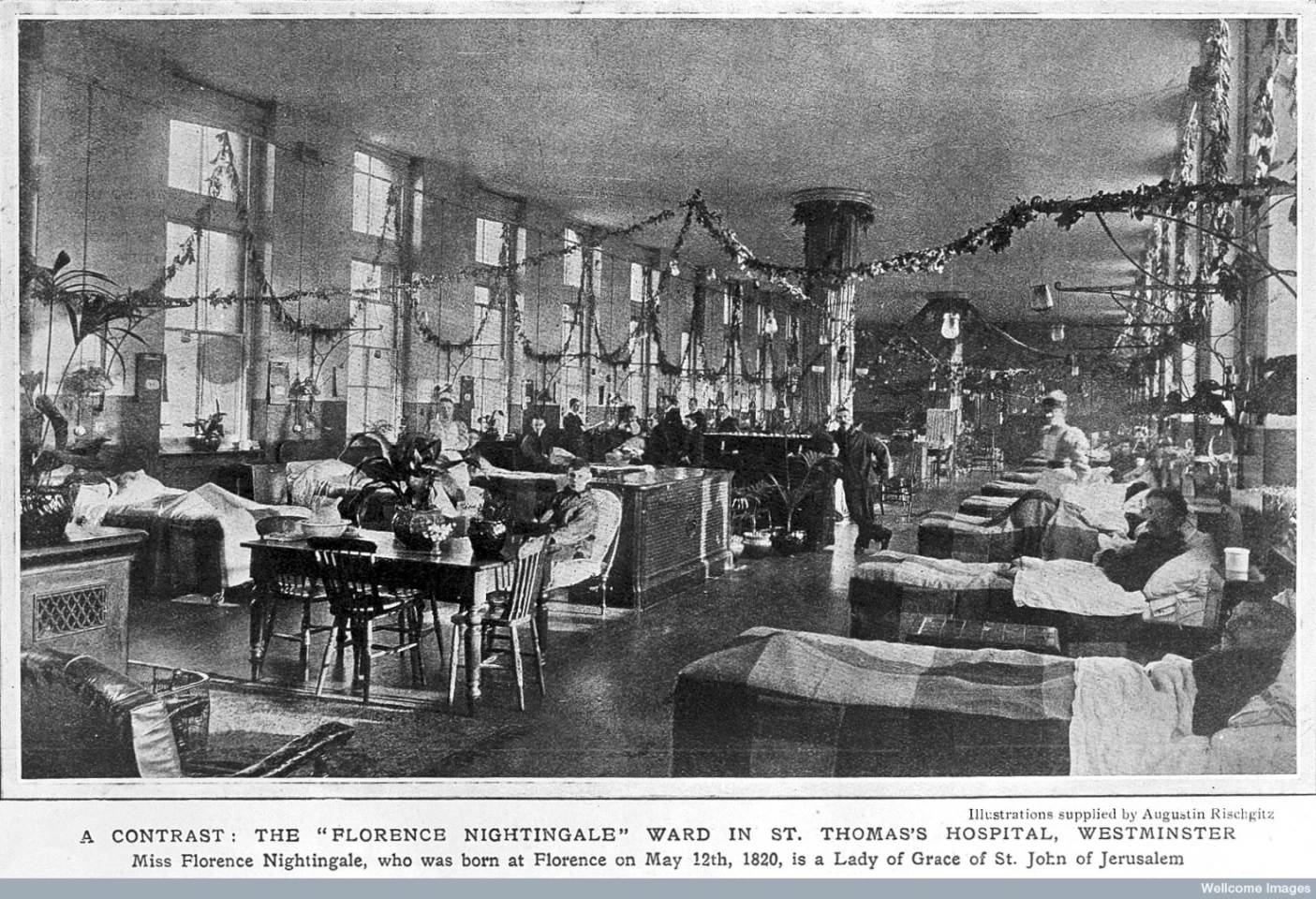

Florence Nightingale's 1858 lectures and the accompanying 'Notes on Hospitals' established the template for hospitals in the Anglophone world until 1939, a pavilion plan type in which Nightingale wards of 26 patients built to her very detailed specifications were separated from each other and only tenuously connected by open cloisters. Any risk of contagion was simply diluted and blown away.

Major Billing's refinements to the system at the original Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore drove huge air-change rates with tall stacks controlled by beautiful deployable umbrella-like chokes set within their shafts. This work was wholly quantified and good data survives in the New York Public Library on the original sizing and commissioning of the Johns Hopkins wards.

Our modeling of these designs in which we place a tuberculosis patient coughing out pathogens shows that these 1875 designs will satisfy the current onerous requirements of the UK National Health Service with very much lower energy and carbon consequences. And the NHS has a severe carbon reduction target by 2050 which it has got almost nowhere delivering.

More than this, research is revealing that gently changing natural environments may speed recovery in hospitals, and deliver greater comfort within the control of the occupants who will tolerate greater environmental diversity as a consequence of their delivery from remotely dictated artificial sealed interiors.