In recent years, we've seen wood used in the construction of traditionally non-wooden things like transistors, bicycles and drones. Now, scientists have used the stuff to create a robotic gripper … which definitely has its selling points.

Ordinarily, robot designers have to choose between either soft rubber grippers or ones made of hard metal. The former are good at grasping fragile objects without breaking them, but will melt if subjected to high temperatures. The latter are much more heat-tolerant, but don't have a particularly soft touch.

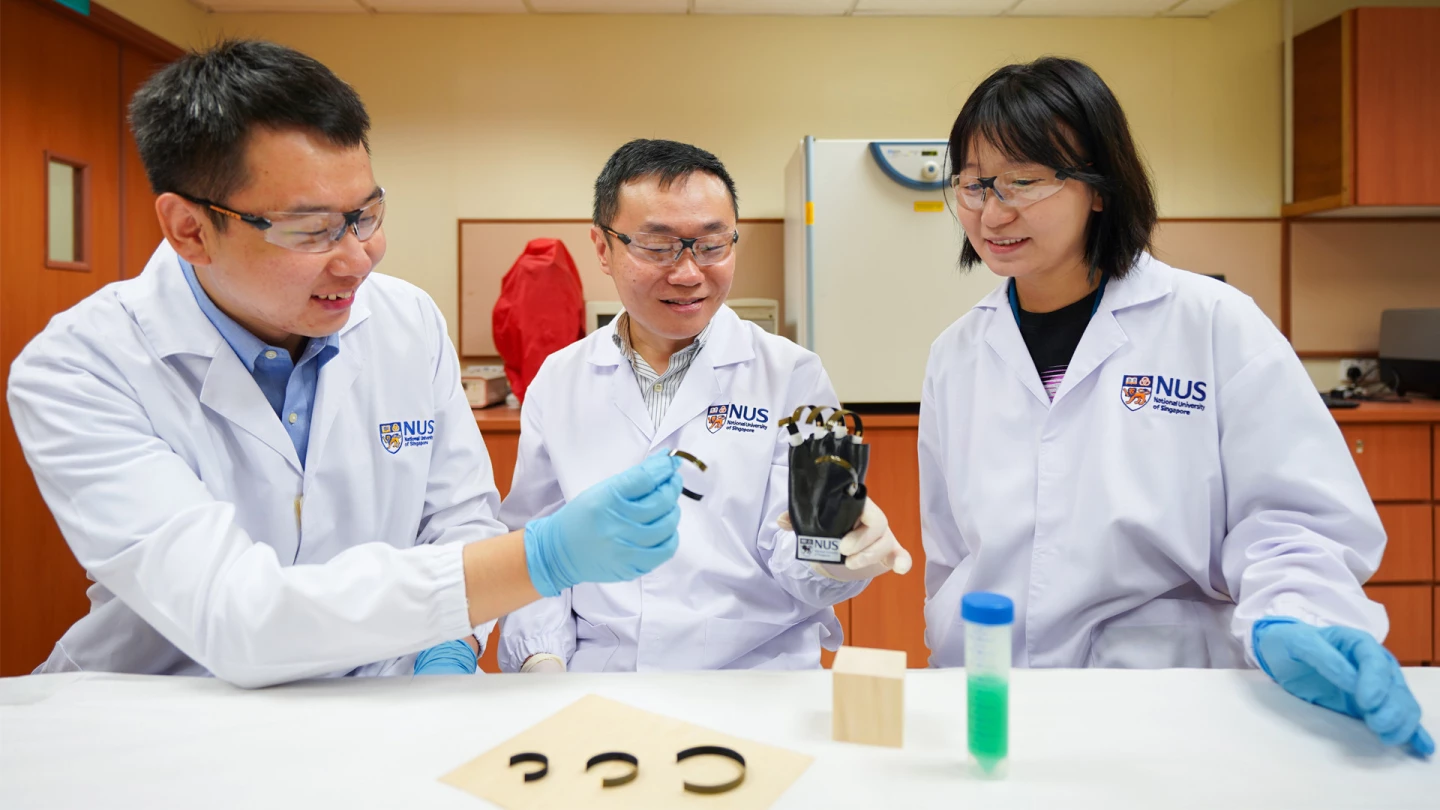

Led by Asst. Prof. Tan Swee Ching, researchers at the National University of Singapore teamed up with colleagues from China's Northeast Forest University to combine the best features of both – using wood.

The scientists started with 0.5-mm-thick strips of Canadian maple, which they treated with sodium chloride to remove all the lignin (an organic polymer which makes up much of wood's cell walls). They then filled the pores left by the missing lignin with a polymer known as polypyrrole, which is good at absorbing heat and light.

Next, a layer of nickel-based water-vapor-absorbing gel was applied to one side of each strip, while a hydrophobic (water-repelling) film was applied to the other. Finally, the strips were placed in heated molds and shaped into curved "fingers." Those fingers were then integrated into a robotic hand, aka a gripper.

When the appendages were placed in an environment with a relative humidity of 95%, the gel on their underside expanded as it absorbed water vapor, causing them to bend outwards.

When they were placed in an environment heated to over 70 ºC (158 ºF), however, water evaporated from the gel – this caused it to shrink, in turn causing the fingers to close inwards. Likewise, when the gel was heated by exposure to a strong light source, it shrank and caused the fingers to close.

Although the appendages would presumably catch fire at some point, they were able to lift a 200-gram (7-oz) weight at an ambient temperature of 170 ºC (338 ºF) without burning.

"Our wooden robotic gripper can spontaneously stretch and bend itself in response to moisture, thermal and light stimulation," said Ching. "It also has good mechanical properties, able to perform complex deformation, wide working temperature range, low manufacturing cost, and is biocompatible. These unique features set it apart from conventional alternatives."

Of course, one might wonder how the gripper could be made to open and close on command, instead of just uncontrollably reacting to its environment.

"Grasping and releasing of the wooden robotic grippers can be achieved by designing some devices and auxiliary equipment," Ching told us. "For example, some wires can be added to the wood to complete the bending actuation under an external voltage to heat up the wires; or a heating plate can be placed near the wood gripper to drive it to bend; a laser/incandescent lamp can also be used to irradiate the wood surface to create heat to control the bending and grasping; we can also spray water around/on the surface of the wood so that it stretches out for releasing the object."

The research is described in a paper that was published in the journal Advanced Materials.

Source: National University of Singapore