Scientists from the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) and the University of Michigan have created the world's smallest autonomous and programmable robots. Each measuring about 200 micrometers wide – roughly twice the width of a human hair – these machines can perceive their surroundings, "think," and act independently without external instructions. According to their developers, such technology could one day monitor the health of individual cells in our bodies or deliver medication to specific locations to treat diseases.

The researchers' major breakthrough was enabling a robot just one-fifth of a millimeter long to move autonomously without external assistance, a challenge scientists have been trying to solve for decades. Physical forces such as drag and viscosity have a much stronger effect on objects at the microscopic scale, making movement through a liquid comparable to swimming through tar at the human scale.

To overcome this challenge, the Penn team designed a new propulsion system. The microrobots are powered by LED light and operate in a hydrogen peroxide solution, which provides the fuel for their movement. The robot generates an electric field that propels the ions in the surrounding solution, which in turn drag water molecules along. The microrobots can adjust this electric field to move in complex patterns and even travel in coordinated groups at speeds of up to one body length per second.

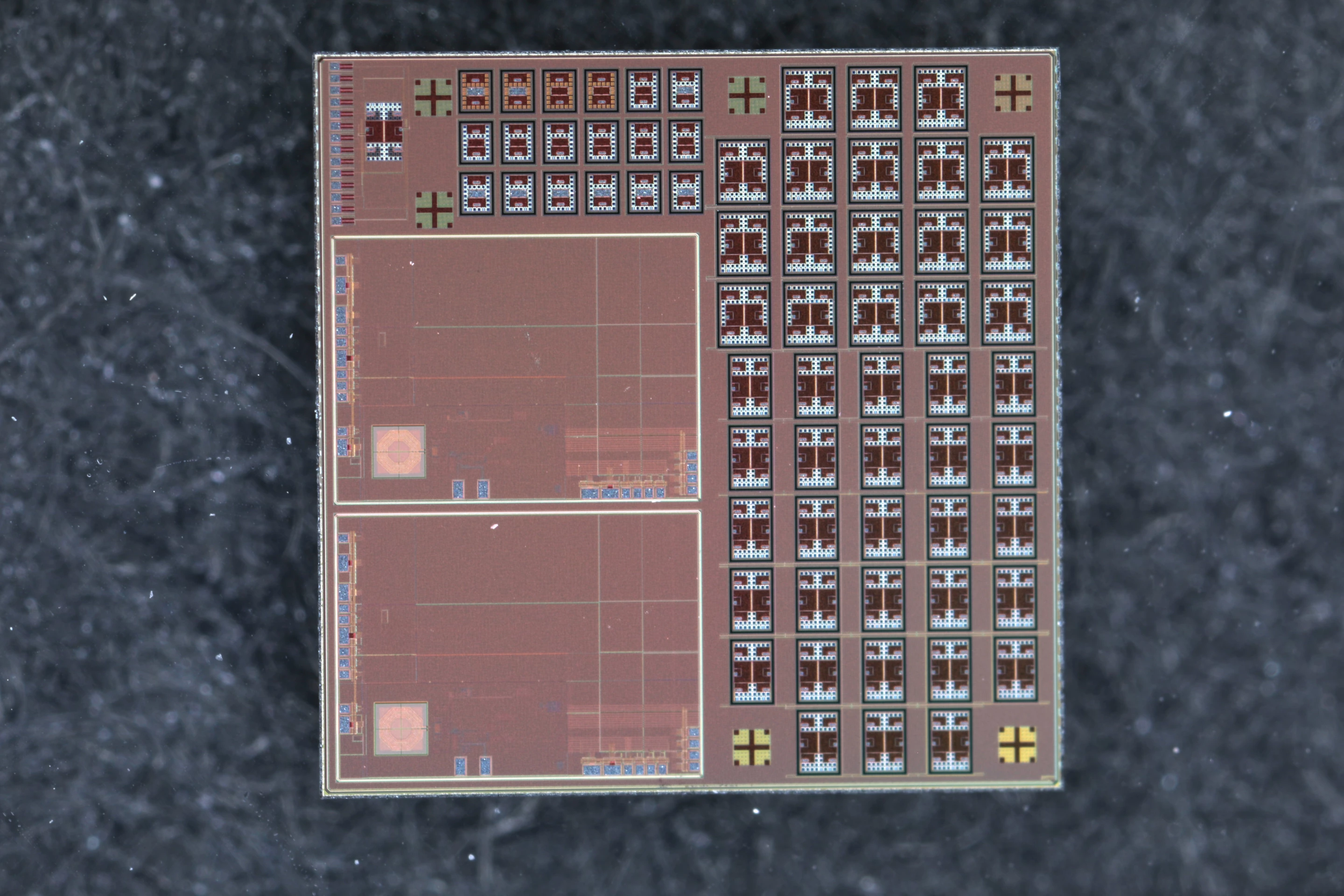

The world's smallest autonomous robot requires the world's smallest computer. That title belongs to a computer developed by David Blaauw's team at Michigan. The researchers adapted their microcomputer to Penn's propulsion system and built a complete computer with a processor, memory, and sensors on a chip less than a millimeter across.

The robot receives light through microscopic solar panels that generate only 75 nanowatts of power – over 100,000 times less than a smartwatch, according to Blaauw. His team had to make the microcomputer circuits operate at extremely low voltages, reducing power consumption by more than a factor of 1,000.

Perhaps the most striking feature is the overall system cost. Although each robot costs about one cent to produce at scale, one might assume that the equipment needed to program and control them would be prohibitively expensive. That is not the case.

"It’s about $100," Marc Miskin, a professor at Penn Engineering and lead author of the study, told me by email. The team has already built a low-cost version of their setup using standard LED diodes, a Raspberry Pi microcomputer, and an imaging system consisting of a smartphone camera fitted with a macro lens. "This system actually performs about as well as our fancy $100k microscope. Because the robot is doing all the hard work, it doesn't need you to tell it what to do," Miskin explained.

The microrobots feature electronic sensors capable of detecting temperature with a precision of one-third of a degree Celsius, allowing them to monitor the health of individual cells. However, several obstacles remain before this technology can be applied to human health.

Just like the cells in our bodies, which require a constant energy supply to survive, the microrobots cannot function without continuous light. "If you turn off the light, the robot turns off and the memory gets cleared," Miskin said. "Turn the light back on, and it will reboot, but won't remember what you programmed it to do. This is a common feature of sub-mm systems, because the total energy you can store (e.g. a battery) scales with its volume, it's extremely hard to store any useful amount in a small space."

But there’s another challenge, in their current version, the robots operate in a 5-millimolar hydrogen peroxide solution, which is toxic to living cells. This makes them unsuitable for medical applications in their present form. The researchers acknowledge this limitation, but it is not insurmountable. Because the robot is electronically integrated, actuators can be swapped freely, you only need to match the operating voltage and required current. "We're actively working on building the corresponding robots, integrating these bio-compatible actuators with circuits, and you'll hopefully see some of these soon," Miskin explained.

Miskin is even more excited about something else: using these robots to assemble microscale components. "Almost everything we build at the microscale these days is made all at once, monolithically," he said. "For example, when we build circuits, we make them out of these complex patterns on big wafers. If you want to change one part of that circuit, you have to rebuild the whole thing."

The researchers argue this could lower costs, speed up design iterations, and even simplify intellectual property. "The microscale is an amazing place," Miskin noted. "Having little agents that humans can program and control could open up all kinds of remarkable doors. I'm cautiously optimistic the best applications have yet to be imagined."

Source: Penn Engineering