The gap in wages between the most- and least-educated US citizens has risen sharply in the last 40-odd years, and new research out of MIT finds that more than half of this disparity can be attributed to a single factor: automation. This bodes poorly.

The gross domestic product value of the USA has risen from US$6.82 trillion in 1980 to more than $20 trillion in 2022. But with nearly three times the pie to go around, not everyone's ended up with more on their plate.

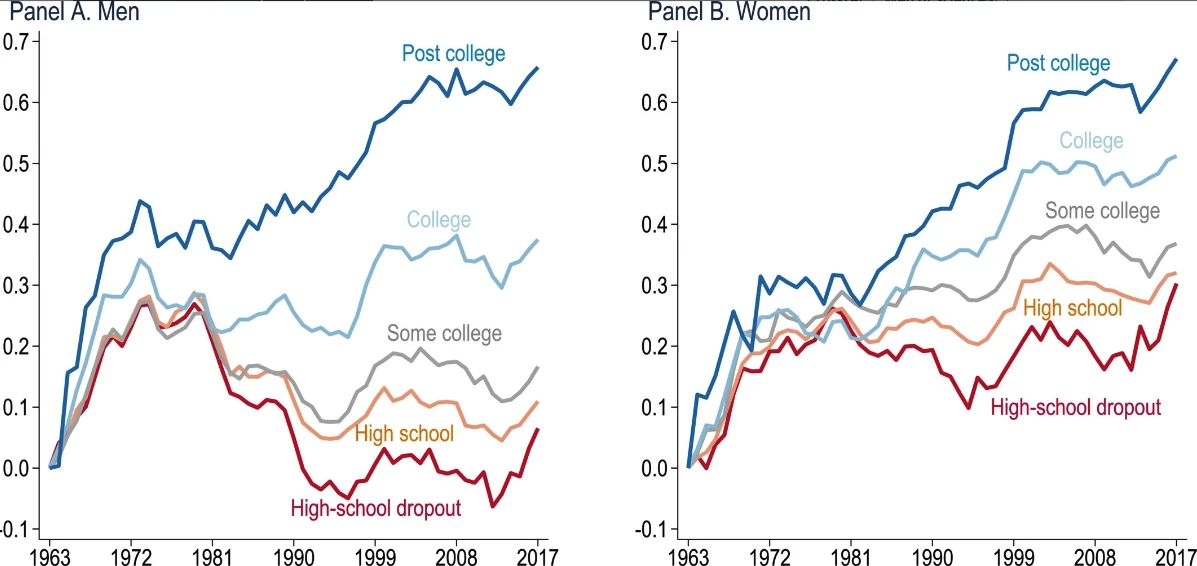

According to MIT Economist David Autor, things have been radically different in the last 40 years than they were in the period between 1963 and 1972, when "wages rose robustly and evenly among all education by gender groups."

While real wages have risen nicely for the postgraduate-educated since 1980, American men without high school degrees were making 15% less in 2016 than they did in 1980, adjusted for inflation. The story is similar in the UK and Germany.

A new study by two more MIT economists, Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, interrogates this relatively recent shift towards increased inequality using a new framework that looks at tasks and allocates them to different types of labor and capital. Put simply, this new model makes it relatively easy to link wage changes in a particular group to task displacement – that is, when machines start doing somebody's job.

It's been obvious for a long time that simple, repetitive jobs don't have a great future, and indeed it's this kind of unskilled work that's been most easily replaced by automation. But the MIT team argues that, even when you control for other factors like the decrease in union participation, the impact of automation on wages for affected groups is considerably worse than anyone thought.

"This single one variable … explains 50 to 70 percent of the changes or variation between group inequality from 1980 to about 2016,” Acemoglu said in a press release. "These are controversial findings in the sense that they imply a much bigger effect for automation than anyone else has thought, and they also imply less explanatory power for other [factors]."

The study also points out a distinction between automation that actually raises overall productivity – say, moving to a robotic factory production line that manufactures things faster and with fewer errors than human workers – and automation that eliminates jobs and saves money for business owners without any increase in productivity – the perfect example being the loss of supermarket cashier jobs in favor of self checkout machines, which don't do the job much better or faster at all.

This kind of "so-so automation," as the authors describe it, is an example of the kind of automation that achieves little more than funneling money up the social strata, away from unskilled workers. It favors one group over another, with no wider benefits for society to offset this increase in inequality.

Why should the better-educated among us care about this, beyond simple empathy for our fellow man? Well, the last 40 years have just been a tasting spoon. The full double-scoop ice cream of automation is being ladled out as we speak, in a technological convergence of artificial intelligence, big data, robotics, connectivity, energy storage and a raft of other factors that promise to make light work of automating a much wider range of jobs.

Capital often sees workers as black box algorithms: given input A, it expects output B. But digital algorithms are getting smarter very quickly, while human brains have arguably done little but atrophy over the last few hundred thousand years. Today, the least educated are finding their earning power mauled by automation and decimated by inflation. Tomorrow, it'll be high school graduates, and then college graduates, at an accelerating pace.

"The pace of automation is often influenced by various institutional factors," said Acemoglu, "including labor’s bargaining power." But there's the problem; what is the bargaining power of labor when capital doesn't want it? Humanity is headed for uncharted waters in this regard. Throughout history, the rich and the poor have struck an uneasy bargain that brought everyone along on the boat ride, because the rich have always needed the poor to do the work. Labor has held capital to account for its worst excesses by occasionally pulling its one big lever: banding together and stopping work. Some have even argued that it's the value of human labor, rather than anything more esoteric and touchy-feely, that underpins the modern Western notion of human rights.

And so we march onward into a future where more and more classes of human labor become less and less valuable. Without some unprecedented structural changes, it certainly looks like the effects will be brutal.

“Acemoglu and Restrepo’s paper proposes an elegant new theoretical framework for understanding the potentially complex effects of technical change on the aggregate structure of wages,” said Patrick Kline, a professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. “Their empirical finding that automation has been the dominant factor driving US wage dispersion since 1980 is intriguing and seems certain to reignite debate over the relative roles of technical change and labor market institutions in generating wage inequality.”

The study is open access in the journal Econometrica.

Source: MIT