Some 180 million years ago, there lived an early mammal – built a lot like the guilty looking fella above – that became the earliest-known ancestor to all mammals on Earth, from the blue whale, to the camel, the rhino, the koala, and your good self.

Frankly, I'd be looking a little guilty myself if I was that guy, he's single-handedly responsible for the multiple unskippable ads in front of YouTube videos, among other grim tragedies. Mammals diverged from the rest of the vertebrate kingdom in the Carboniferous period, some 300-odd million years ago, distinguishing themselves from fish, reptiles, birds and amphibians with mammary glands for feeding their offspring with milk, as well as fur or hair, three middle-ear bones and a neocortex region in the brain.

It was, and remains, a potent recipe. The mammalian class branched out in countless different directions from that point, and eventually more or less took over much of the planet, some burrowing underground, some making their home on the plains, some climbing up into the trees like our primate ancestors, and others returning to the oceans to evolve into some of the biggest creatures that have ever lived on Earth.

All modern mammals, however, have a single common ancestor, according to genetics researchers, and while little is known about this animal, an international team of researchers has now computationally reconstructed the organization of its genome.

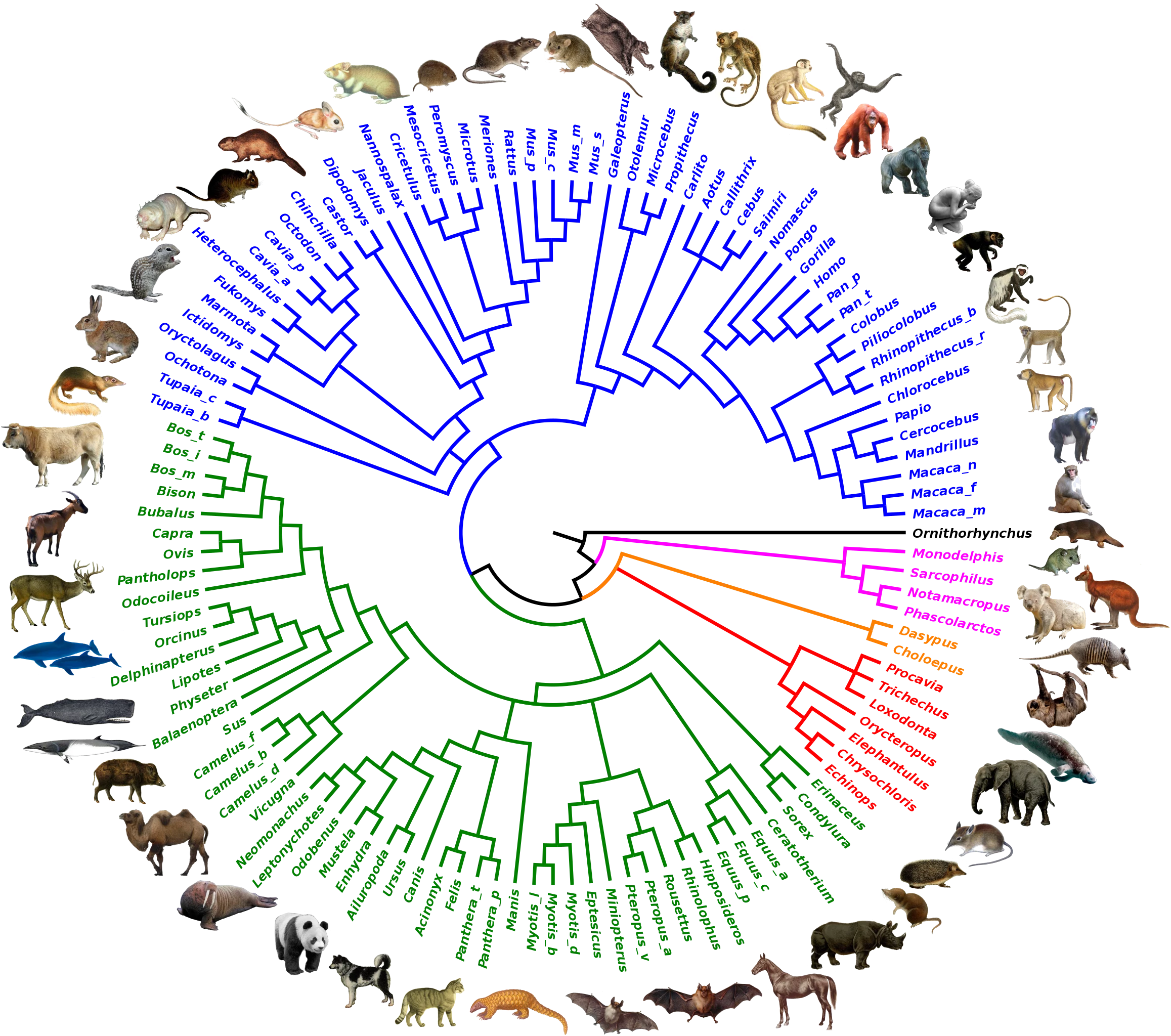

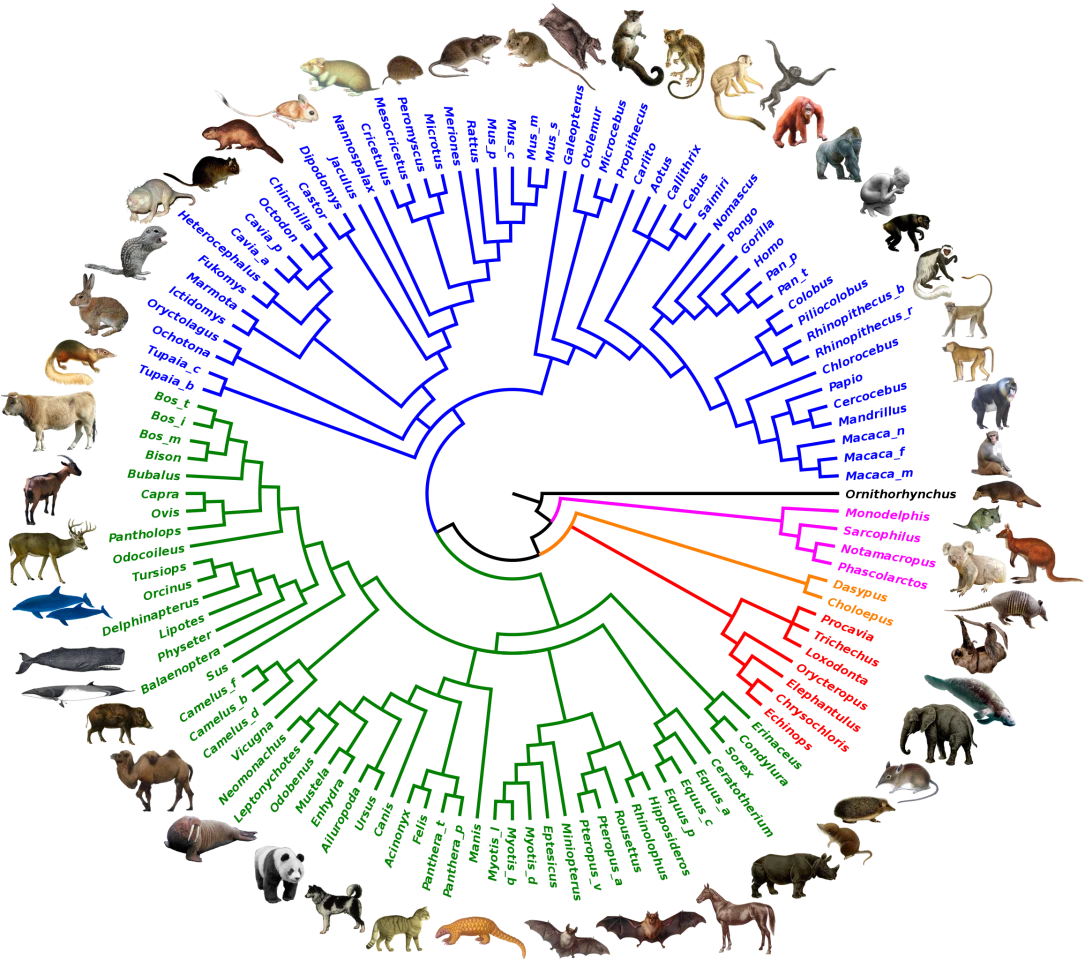

Led by evolution and ecology specialists at UC Davis, the team analyzed high-quality genome sequences from 32 living mammal species, including humans, manatees, bats, pangolins, rabbits and wombats, using the genomes of chickens and Chinese alligators as comparison groups from outside the mammalian class.

The team found 1,215 blocks of genes that consistently appear, in order and on the same chromosome, across all 32 genomes. The researchers deduced that our common ancestor had 21 chromosomes, including 19 autosomal chromosomes and two sex chromosomes. They found nine whole chromosomes, or fragments thereof, where the order of genes matched up perfectly with the chromosomes of modern birds, demonstrating the extraordinary stability of some genetic sequences, even across more than 300 million years of evolution.

The sections between these well-preserved chunks had more repetitive sequences, and proved more susceptible to the breakages, duplications and rearrangements that drive genetic evolution.

Tracing the chromosomes forward in time, the researchers were able to track the rate of chromosome rearrangement across different lineages, noting for example an acceleration in genetic rearrangement around 66 million years ago, right about when an asteroid strike ended the rule of the dinosaurs and cleared the path for mammals to take over as the dominant group on the planet.

The research is open access at PNAS.

Source: UC Davis