Researchers in Canada have diagnosed an advanced, malignant bone cancer – in a dinosaur. Using the kinds of diagnostic techniques used in humans, a team of cancer professionals examined a large growth on the long-dead animal’s leg bone, marking the first time such a diagnosis has been made for a dinosaur.

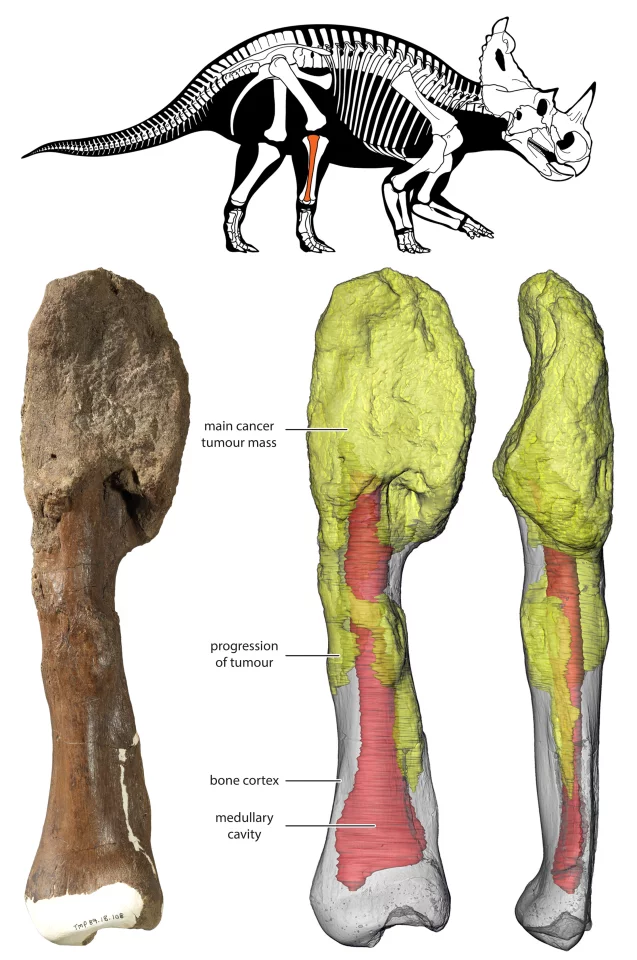

The specimen is a Centrosaurus apertus, a horned dinosaur in the same general family as the famous Triceratops. Dating back between 76 and 77 million years, the fossil was originally discovered in Alberta back in 1989, and attention was drawn to a malformed mass on the end of the animal’s fibula, the lower leg bone.

Originally, the deformation was chalked up to a broken bone that hadn’t healed well. But osteopathologist Mark Crowther noticed the strange bone while visiting the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, and decided to investigate it more closely.

A team of scientists was assembled to study the fossil, including experts in fields like pathology, radiology and orthopedic surgery, along with those that specialized in dinosaur diseases. The bone was examined, casts were made, and CT scans were performed. Then, the fossil was sliced into thin sections and studied under a microscope. Altogether, these tests allowed the scientists to reconstruct a cross-section of the entire bone, inside and out, to determine disease progression.

In doing so, the researchers were able to reach a diagnosis: osteosarcoma. This type of cancer affects the bones of humans and other animals, most often arising at the ends of long leg bones, as was the case with this Centrosaurus.

The team confirmed the diagnosis by comparing the affected bone to a fibula from a healthy dinosaur of the same species, as well as a human fibula with osteosarcoma. In this instance the disease was very advanced, and knowing the behavior of osteosarcoma the researchers say that it would likely have spread throughout the dinosaur’s body by time of death.

Interestingly though, it doesn’t look like the cancer was the cause of death. The fossil was found in a massive bonebed with many other Centrosaurus, suggesting it died suddenly as part of a herd.

“The shin bone shows aggressive cancer at an advanced stage,” says David Evans, co-author of the study. “The cancer would have had crippling effects on the individual and made it very vulnerable to the formidable tyrannosaur predators of the time. The fact that this plant-eating dinosaur lived in a large, protective herd may have allowed it to survive longer than it normally would have with such a devastating disease.”

The research was published in the journal The Lancet Oncology. The team describes the work in the video below.

Source: McMaster University