From feeding cancer cells to triggering depression, there are a host of reasons why a high-fat diet isn't optimal for human health. Now, researchers at the Penn State College of Medicine have added another discovery to the long list of adverse effects from high fat intake: a disruption in brain cells that regulate how rat stomachs fill and empty. In a study using the rodents, after just two weeks of exposure to a high-fat diet, it was found that these cells ceased operating correctly, blocking the pathway that causes a decrease in calorie consumption after the stomach is full.

In the study, 205 rats were divided into control groups and test groups. The control groups were fed a standard diet, while the test groups were fed a high-fat/calorie diet. Rats in both groups stayed on the diets for either one, three, five or 14 days.

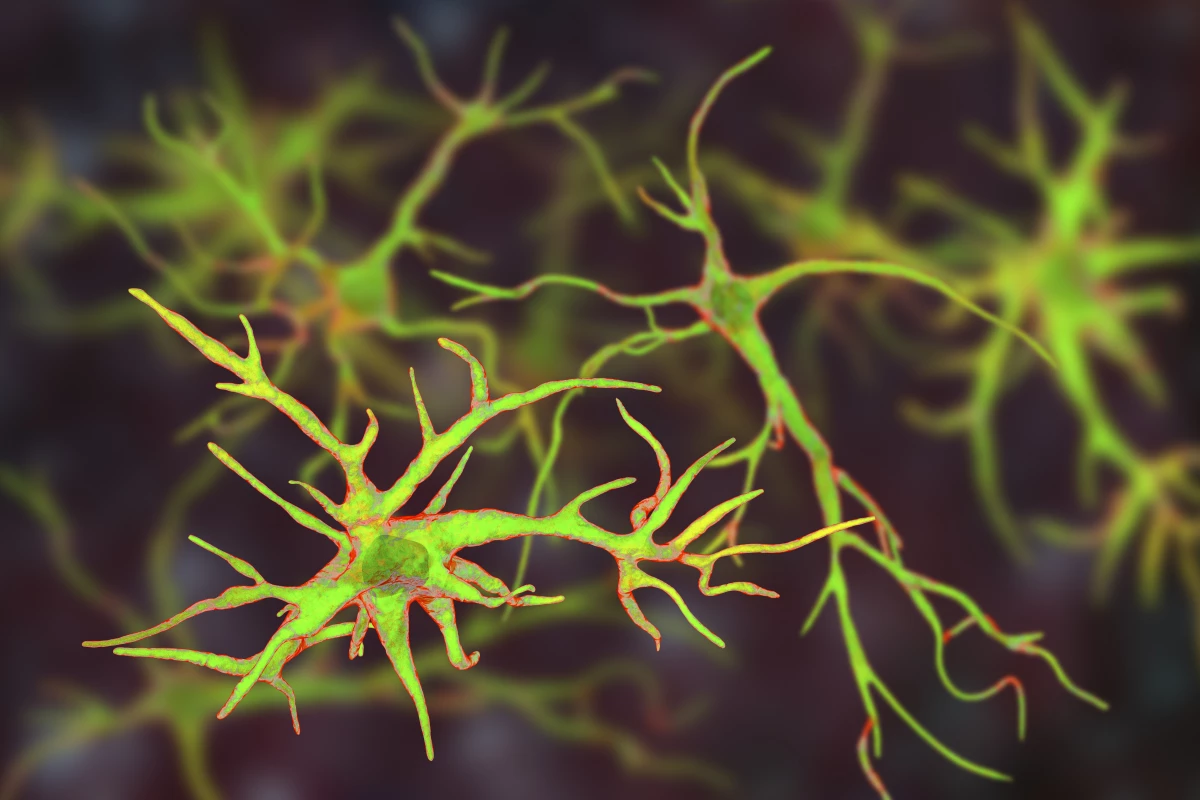

The researchers then monitored the effects the diets had on large, branching cells in the brain called astrocytes. These cells are not neurons themselves, but they can regulate neurons. Their activity has been linked to both increasing and decreasing inflammation, and they've been found to play a role in Parkinson's disease.

This study looked at the ability of astrocytes to trigger the release of chemicals known as gliotransmitters, which work to stimulate the neural pathways that control how the stomach expands and contracts in the presence of food. It found that the astrocytes were the most active after three to five days of the high fat/calorie diet, during which time they worked correctly to ramp down calorie consumption after a meal. However at around day 10, the cells began to malfunction.

"Over time, astrocytes seem to desensitize to the high-fat food," said study coauthor Kirsteen Browning. "Around 10-14 days of eating a high-fat/calorie diet, astrocytes seem to fail to react and the brain’s ability to regulate calorie intake seems to be lost. This disrupts the signaling to the stomach and delays how it empties.”

The disruption in the normal feelings of fullness after a meal can lead to obesity. However, even though the researchers identified the effects of fat on astrocytes, they're not quite sure how the process ties into the overeating model. Nor are they sure if the rat observations will apply to humans, and they indicate that further testing is necessary.

“We have yet to find out whether the loss of astrocyte activity and the signaling mechanism is the cause of overeating or that it occurs in response to the overeating," said Browning. "We are eager to find out whether it is possible to reactivate the brain’s apparent lost ability to regulate calorie intake. If this is the case, it could lead to interventions to help restore calorie regulation in humans.”

The study was published in The Journal of Physiology.

Source: Penn State College of Medicine via EurekAlert