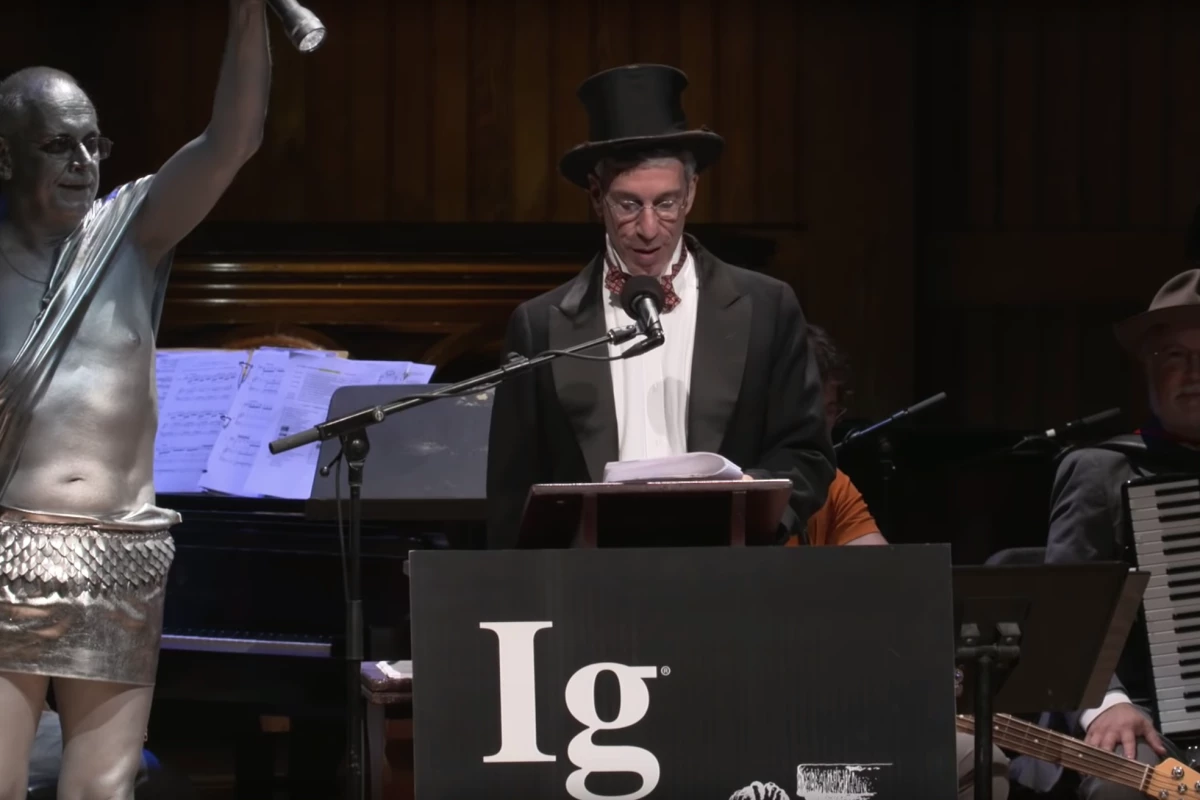

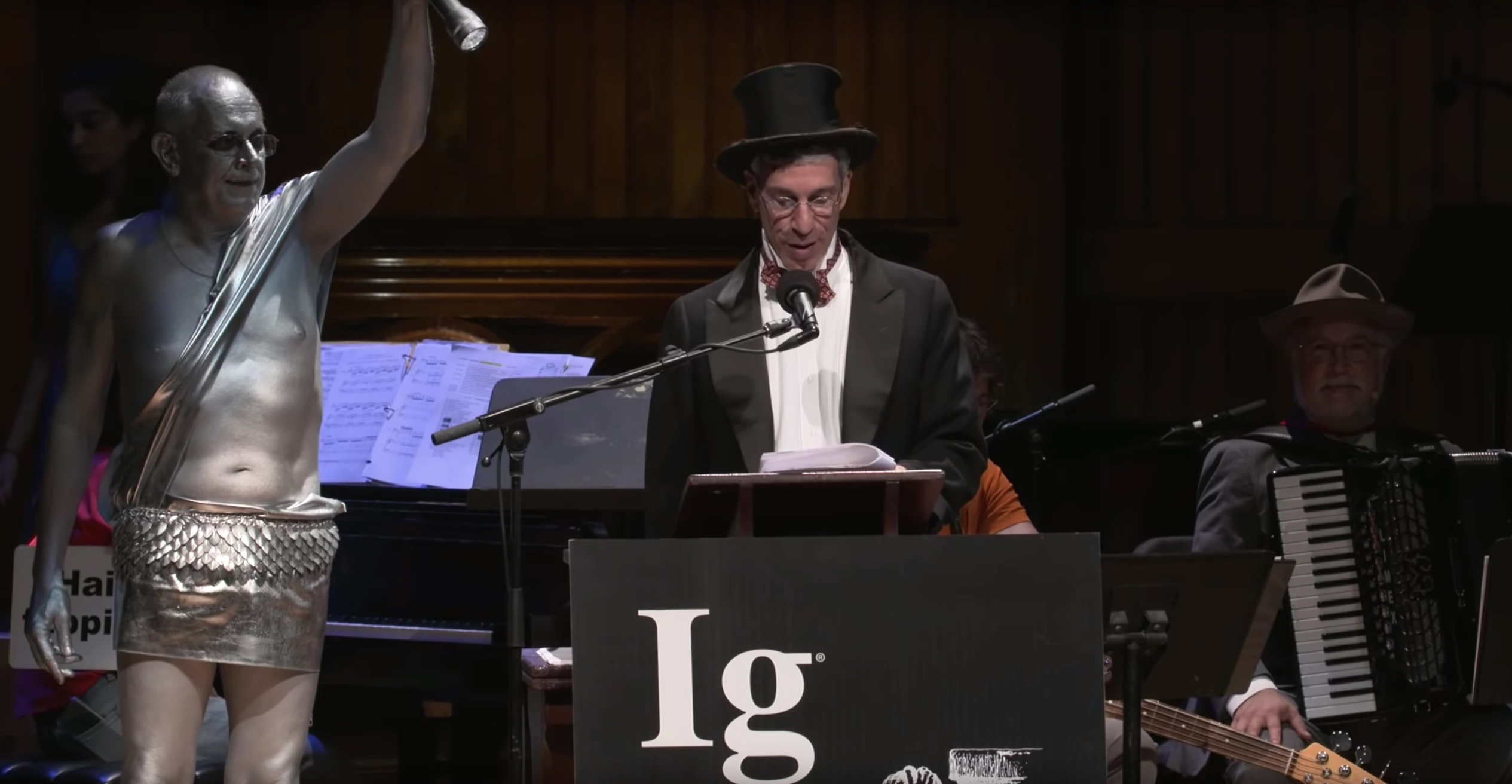

Since 1991, the Ig Nobels have honored scientific achievements "that first make people laugh, then make them think." This year's gala ceremony at Harvard University's Sanders Theatre saw Nobel Laureates hand out awards to winners who turned their considerable intellects to examining everything from cubed wombat poo to the temperature differential of left and right testicles.

The 10 winners in the 29th First Annual Ig Nobel Prize didn't pocket the roughly US$1 million in prize money that the winners of the slightly more serious awards from which the Ig Nobels derive their name took home, but the competition is just as farce – I mean fierce – and they no doubt ended the night with a smile on their faces.

This year's winners, covering 10 categories, are as follows:

Medicine Prize (Italy, The Netherlands): Pizza protecting against illness and death? There would be plenty of pizza lovers thrilled at such a seemingly unlikely prospect. But Silvano Gallus and his team found the popular dish may indeed lower the risk of some cancers and heart attack. There's just one catch – the pizza must be made and eaten in Italy. This is one study we would have loved to participate in, and apparently the team had plenty of takers, publishing no less than three papers on the subject: "Does Pizza Protect Against Cancer?", "Pizza and Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction," and "Pizza Consumption and the Risk of Breast, Ovarian and Prostate Cancer."

Medical Education Prize (USA): You'd hope that training a surgeon would be more difficult than training a dog (although some pet owners may have their doubts). But the team of Karen Pryor and Theresa McKeon found that the "clicker training" technique popular with dog trainers can also prove more effective than being taught by demonstration alone. Medical students trained using clicker training in two orthopedic surgical skills performed them more accurately (although more slowly) than the control group taught by demonstration alone. They detailed their work in the paper, "Is Teaching Simple Surgical Skills Using an Operant Learning Program More Effective Than Teaching by Demonstration?"

Biology Prize (Singapore, China, Germany, Australia, Poland, USA, Bulgaria): It's well known that birds can sense magnetic fields, but various insects, including the American cockroach, also boast this ability. An international team analyzing this cockroach magnetoreception has found alive and dead cockroaches exhibit different magnetic properties. At its face, this might not seem to hold much in the way of potential applications, but the finding, detailed in the paper, "In-Vivo Biomagnetic Characterisation of the American Cockroach," could help in the development of new magnetic sensors.

Anatomy Prize (France): It's common for one testicle to be bigger than the other and one to hang lower than the other. Now, thanks to Roger Mieusset and Bourras Bengoudifa, we know this lack of symmetry extends to scrotal temperature. Enlisting the services of postal employees and bus drivers who kindly allowed probes to be connected to their nether regions and temperatures recorded, the researchers found that "the lack of thermal symmetry" of scrotal temperatures was observed whether the person was clothed or naked – we just hope the bus drivers weren't taking passengers while in the latter state. Details are in the paper, "Thermal asymmetry of the human scrotum."

Chemistry Prize (Japan): Raising kids can be a messy business, but have you ever asked yourself exactly how much saliva a five-year-old can produce in a day? No? Well a team of Japanese researchers has, and decided to find out. Both boys and girls were enlisted for the study, which found that the estimated salivary volume produced per day was about 500 ml. We're not sure if measuring the saliva volume involved a lot of spitting into a beaker on the part of the study subjects, but the details can be found in the team's paper, "Estimation of the total saliva volume produced in five-year-old children."

Engineering Prize (Iran): Keeping the messy kid theme going, Iman Farahbakhsh took out this year's Engineering Prize by inventing a diaper-changing machine. Before all you parents out there start thinking this is the best idea ever, unfortunately the machine doesn't actually change the child's diaper (we suspect Farahbakhsh may have won a Nobel Prize if it did). Rather, it's basically a restraining device that looks like an oven, into which the child is seated and secured so the human diaper-changer can perform their task unhindered. The apparatus (patent awarded) also sprays parts of the child down and then dries them. Full details are available with the patent application.

Economics Prize (Turkey, The Netherlands, Germany): Food service workers are told to never directly handle food after handling money – and with good reason. As one of the most frequently passed around items on the planet, paper money can pick up all kinds of bacterial nasties. But not all bank notes are created equal. While some places, such as the US and the Euro zone, have stuck with paper money manufactured from cotton fiber, many countries have switched to plastic banknotes for the sake of security and durability. But apparently attractiveness to pathogens wasn't a consideration, with Habip Gedik, Timothy A. Voss, and Andreas Voss finding polymer notes, specifically the Romanian Leu, proving worse than their paper counterparts for carrying multi-drug resistant pathogens. Their findings are outlined in the paper, "Money and Transmission of Bacteria."

Peace Prize (UK, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, USA): Being subjective, pleasure and pain are notoriously hard to quantify. But that didn't stop an international team attempting to measure the pleasure of scratching an itch. Inducing itching using cowhage spicules, the team found itch intensity and the associated pleasure from scratching that itch differed based on location – for example, itch intensity and scratching pleasurability ratings were higher for the ankle and back compared to the forearm. Additionally, the pleasurability derived from scratching an itch on the ankle lasted longer than for itches on the back of forearm. The team's paper was entitled, "The pleasurability of scratching an itch: a psychological and topographical assessment."

Psychology Prize (Germany): This one was a long time in the making. In 1988, Fritz Stack was part of a team which published a study that found facial expressions can affect emotional experiences. Having study participants hold a pen in their mouths in such a way to make them smile, resulted in them finding a cartoon funnier. But some 30 years later, following unsuccessful attempts to replicate the team's findings, in his paper "From Data to Truth in Psychological Science. A Personal Perspective," Stack admitted that "overall, there was no significant effect" and "the original effect was weak and fragile, not robust enough to show up under changing conditions." At least he came away with a prize to his name.

Physics Prize (USA, Taiwan, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, UK): This was a study that caught our attention late last year. Researchers had discovered how the wombat manages to produce cube-shaped poo. It's the only animal in the world known to do this, and the team found it's all to do with the way the marsupial's intestine stretches. The researchers still don't know for sure why wombats evolved to produce cube-shaped excretions (the belief is it allows the poo to be more easily stacked to serve as territorial markings), but the fact they have and researchers have sought to find out how could lead to the development of new manufacturing processes. The researchers revealed their discovery in their paper, "How Do Wombats Make Cubed Poo?"

Congratulations to all the winners of this year's awards. You can watch the full ceremony in the video below.

Source: Improbable Research