A new article in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs describes three cases of accidental high LSD overdoses resulting in strangely positive outcomes, including the story of one woman who inadvertently took 500 times a normal dose. New Atlas spoke to Mark Haden, one of the authors of the report, to discuss LSD toxicity and how extreme psychedelic experiences can sometimes be beneficial.

She was frothing at the mouth

In 2015 a 46-year-old woman, referred to in the case study as CB, consumed what she thought was a line of cocaine. After around 15 minutes CB suspected something was wrong and called her roommate who quickly realized that instead of consuming cocaine, CB had actually ingested pure concentrated LSD in powder form.

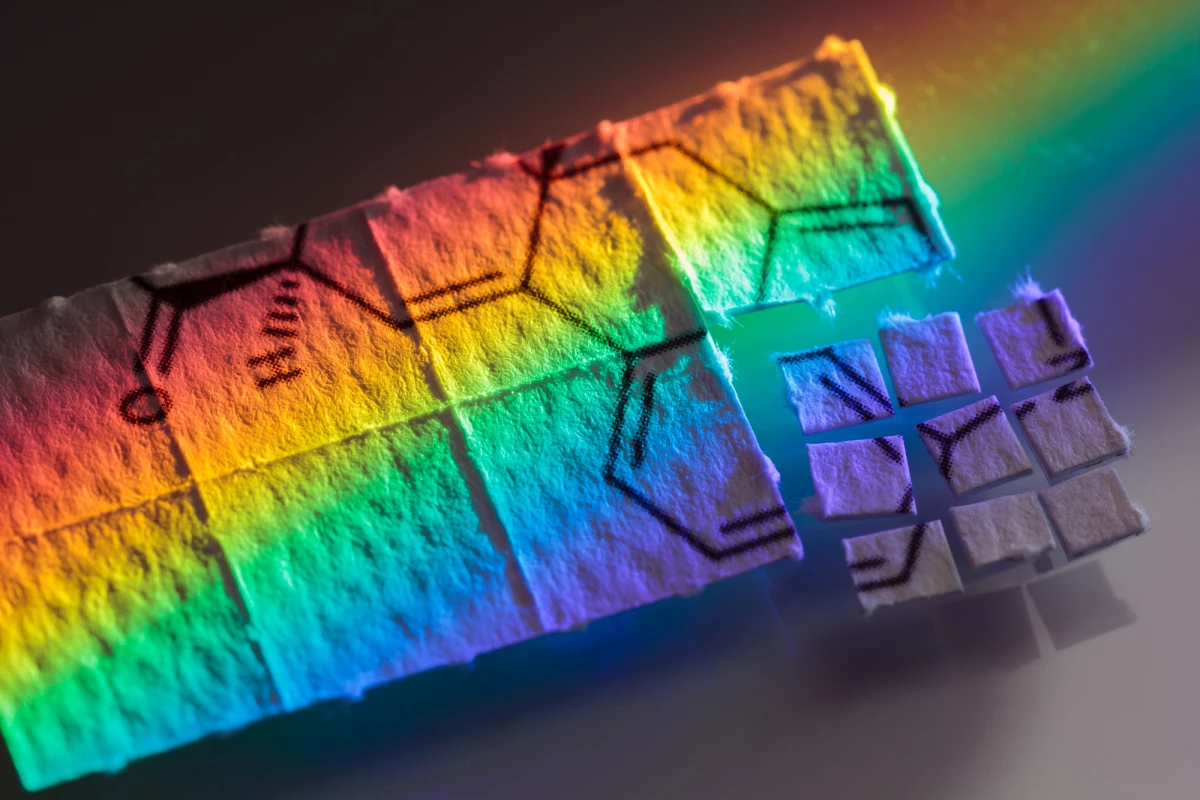

The roommate estimated CB had taken around 55 milligrams of LSD. That may not sound like much, but LSD is an extraordinarily potent compound, active in minute volumes. A general recreational dose is around 100 micrograms. CB had consumed about 550 times a standard active dose.

CB has little recollection of the first 12 hours of the experience, other than frequently vomiting. The second 12 hours she suggests felt “pleasantly high,” although her roommate’s recollection is that she was frequently frothing at the mouth and vocalizing random words. CB eventually returned to a relatively coherent state after around 34 hours in total, however, it was from this point on things arguably started to get really strange.

For over 20 years CB had suffered extreme chronic pain in her feet after contracting Lyme disease. In the decade leading up to the accidental LSD overdose, CB took anywhere from four to eight morphine pills every day. The day after she recovered from the LSD experience her foot pain disappeared and she stopped taking morphine altogether, yet suffered no withdrawal symptoms whatsoever.

CB’s pain did slowly return a few days later. She began taking small doses of morphine again, in conjunction with microdoses of LSD. After a few months she stopped taking the morphine permanently, suffering no typical opiod withdrawal symptoms.

Mark Haden, Executive Director of MAPS Canada and one of two authors on the new article, calls this case study “shocking,” suggesting it’s somewhat unprecedented to study a case where such an extraordinarily high dose of LSD has resulted in a reduction of chronic pain and an ability to suddenly stop taking morphine with no regular withdrawal symptoms.

But the million-dollar question is exactly how this could possibly work, and it is this question that sits at the heart of most modern psychedelic science. As researchers rapidly discover incredible potential uses for psychedelics, from MDMA treating PTSD to psilocybin treating major depression, the fundamental mechanisms underpinning these effects still remain a mystery.

“The glib answer to that question is a sort of rewiring of the brain, but what does that actually mean?” says Haden in a conversation with New Atlas. “New neural networks get formed. We all know we get into certain habits. If you are used to putting your jacket on with your right arm in first, try it the other way around, and you’ll realize how difficult it is to change neural pathways. So our lives are full of neural pathways, and LSD or psychedelics generally, seem to do something to create new neural pathways. That is a really superficial answer. We don’t really understand what that means.”

Haden says, in terms of LSD specifically helping reduce chronic pain, the answer is just as abstract and hard to fathom. Very little research has been done to directly investigate the relationship between LSD and chronic pain. Alongside the CB case study, there are other anecdotal cases suggesting LSD experiences can be beneficial for those suffering from chronic pain, but this is certainly an area lacking in rigorous clinical research.

A few small studies in the 1960s did experiment with LSD’s analgesic qualities, offering some intriguing results. One particular study, published in 1964, compared the effects of a 100 microgram dose of LSD against a couple of common analgesics. Fifty “gravely ill” patients with “severely intolerable pain” were administered the three drugs in double-blind conditions.

Although LSD did not offer acute speedy analgesia compared to the other two drugs, by the three hour mark it was unexpectedly found to be the most effective of all the drugs studied. Plus, the long-term efficacy of a single dose was impressive with nearly 75 percent of subjects reporting analgesic effects from LSD seven hours later, and almost 50 percent reporting the benefits persisting 19 hours after administration.

While there may at least be some kind of way to understand how a massive dose of LSD could result in improvements to an individual’s chronic pain, another case study described in the new article presents perhaps an even stranger mystery.

“It’s over”

AV had been hearing voices and suffering from depression for years before officially entering the mental health system at the age of 12. Over the next three years her negative symptoms intensified. She was ultimately diagnosed with bipolar disorder, but inconsistently took her prescribed medications. At the age of 15 AV suffered a severe manic episode resulting in an extended stay in a mental health hospital.

AV was not unfamiliar with recreational drugs. She frequently used cannabis, and reported trying psilocybin mushrooms, LSD and MDMA on different occasions.

A few months after leaving hospital AV went to a summer solstice party. She decided to take a regular 100 microgram dose of LSD, however, the supplier had miscalculated the dosages and AV ended up consuming around 1200 micrograms, over ten times a standard dose. After six hours of behavior that was simply reported as “erratic,” an ambulance was called to come pick up AV who at the time was allegedly suffering seizures.

“AV’s father reported that when he entered the hospital room the next morning, AV stated, 'It’s over.' He believed she was referring to the LSD overdose incident, but she clarified that she meant her bipolar illness was cured,” Haden and co-author Birgitta Woods write in their article.

The change in AV’s demeanor and symptoms were virtually instantaneous. Three weeks after the incident her mental health team noted her mood to be happy and balanced. Three months later she was still stable, with no signs of recurrent depression or mania.

By the following year AV had managed to safely stop taking her lithium medication. For the following 13 years AV suggests she was entirely free of any mental health issues. She did eventually suffer from postpartum depression following the birth of both of her children, however, her mental health improvements were essentially sustained for almost 20 years following the single LSD overdose incident.

“AV reports that after the LSD overdose incident she experienced life with a ‘normal’ brain, whereas her brain felt chemically unbalanced before the incident,” write Haden and Woods.

The final case study discussed in the article is perhaps the most straightforward. It describes a young women accidentally ingesting 500 micrograms of LSD thinking it was a much smaller dose. The woman did not know it at the time but she happened to be two weeks pregnant.

She went on to give birth to a healthy boy, and eighteen years later that boy grew up to be a well-adjusted and intellectually strong man. The case study suggests the accidental overdose of LSD in the early stages of a woman’s first trimester did not result in damage or negative development effects to her growing son.

“One of the least toxic substances on the planet”

Haden suggests this particular case study is not extraordinarily novel as, “we pretty much knew that LSD doesn’t harm fetuses.” However, this third case study, alongside the other two, does affirm something researchers already suspect … LSD is an incredibly non-toxic drug. In fact Haden says there is isn’t any evidence he is aware of chronicling a human dying from an overdose of LSD.

“Albert Hoffman, who invented LSD, speculated it was one of the least toxic substances on the planet,” Haden tells New Atlas. “What we do know is that people can take thousands of times the normal dose. There is evidence of that, and you can’t take a thousand times a dose of water. What’s a dose of water, maybe a glass? If you tried to drink a thousand glasses of water it would kill you.”

It may sound extreme to suggest there are no direct cases of humans dying from LSD toxicity. Undoubtedly there have been many reports, both in scientific literature and the media, attributing deaths to LSD, but how many of those fatalities can be explicitly linked to drug toxicity?

A valuable article published in 2018, from researchers David Nichols and Charles Grob, investigated five recent cases of sudden death reportedly linked to LSD toxicity. Nichols and Grob analyze each individual case, clearly demonstrating LSD toxicity was not the cause of the fatalities. The article highlights how certain old propagandist perceptions of LSD toxicity still persist, not only in hyperbolic media reports but also in professional scientific perspectives.

“LSD does not have the degree of physiological toxicity alleged by recent reports in the professional literature and the media,” Nichols and Grob conclude in the article. “These reports have caused confusion by distracting from what is likely the true causes of these reported deaths, excessive physical restrains and/or psychoactive drugs other than LSD.”

None of this means LSD is a harmless drug. But, it still is unclear to this day how high a dose is necessary to kill, or at the very least permanently damage, a human being.

The sad tale of an elephant named Tusko

Animal toxicity studies exploring high LSD doses have delivered notably mixed results. Perhaps the most disturbingly unsettling LSD animal experiment came in a controversial 1962 study. A trio of scientists based at the University of Oklahoma wondered what would happen if a massive male Asiatic elephant were injected with a huge dose of LSD.

Within minutes of being injected with 297 millgrams of LSD the elephant named Tusko collapsed and began seizing. Over the following 100 minutes Tusko was injected with an anti-psychotic drug, and then a tranquilizer, but sadly the animal didn’t survive the experience.

The so-called Tusko experiment was controversial, not only due to its blatant mistreatment of an animal, but also due to its many procedural problems. For two decades it was often cited as an indication of how toxic LSD could be, but this conclusion never took into account the effect of the extra drugs Tukso was subsequently administered. Plus, there have been claims the animal was also dosed with amphetamines.

In 1984 a researcher named Ronald Siegel recreated the Tusko experiment but under much more controlled conditions. Siegel administered two similarly high LSD doses to a pair of African elephants. The drug certainly resulted in some unusual behaviors, but the animals otherwise tolerated the high doses quite well suggesting it most likely wasn’t LSD toxicity that killed Tusko.

Substance + Dosage + Context = Damage

Haden makes it clear that these case studies are not presented to justify or advocate recreational drug use, but instead to help better understand how psychedelics could offer novel therapeutic possibilities. And, while it may seem increasingly clear LSD is a relatively safe drug in terms of toxicity, that does not imply it cannot cause lasting damage. Instead, Haden says the main concern one should have with LSD is the context it is taken in.

“You have to think about damage from the point of substance, dosage and context,” Haden says. “To get damaged you have to have, usually, a bad context. When people who are unwitting take a substance and then are in a horrible environment it can do harm. So that’s why all the research is very very careful to structure the context.”

This focus on the fundamental importance of context is one consistently noted by many current psychedelic science researchers. The therapeutic efficacy of much modern research, particularly in reference to psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy using substances such as psilocybin and MDMA, is often pointed to as significantly determined by psychological, environmental, and structural contexts.

This is to say, a single dose of a psychedelic drug doesn’t, for example, inherently cure a person’s depression, but instead it is the therapeutic context it is administered in that leads to the positive outcome. Influential psychedelic researcher Robin Carhart-Harris and his team at Imperial College London effectively explained the fundamental importance of context in a key 2018 journal article.

“It is argued that neglect of context could render a psychedelic experience not only clinically ineffective but also potentially harmful – accounting, in part, for the negative stigma that still shackles these drugs,” Carhart-Harris and his team write.

And before anyone decides to consume a massive dose of LSD to cure whatever ails them, Haden offers a key reminder. These accidental large LSD doses did not result in experiences any of the subjects described as fun or pleasant.

“The message that I think comes from these experiences is that the experience itself is horrible,” Haden says. “I’m lying there, vomiting, blacking out. It’s a very, very unpleasant experience. None of the participants said they have any fun at all during the experience. So it’s a very unpleasant experience.”

The new case report article was published in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs.