If the idea of living robots made out of frog cells isn't quite weird enough for you, how about living robots made out of frog cells with the ability to reproduce? These first-of-a-kind "Xenobots" are not just a marvel of modern bioengineering that could open up exciting possibilities in regenerative medicine, but also represent a type of biological reproduction never before observed in science.

These new robots build on research from last year in which scientists at the University of Vermont (UVM), Tufts University, and Harvard University developed living robots out of cells harvested from the Xenopus laevis frog. These robots were designed by supercomputer and assembled by hand, running on stored embryonic energy to swim around Petri dishes carrying out different tasks depending on their design, including pushing around material in their environment and even forming replicas out of loose cells.

“These can make children but then the system normally dies out after that," says Sam Kriegman, lead author of the study. "It’s very hard, actually, to get the system to keep reproducing.”

To afford their Xenobots such capabilities, the scientists again turned to a supercomputer-based evolutionary algorithm to test out billions of different potential body shapes. These included triangles, squares, pyramids and starfishes, with the goal being to land on a design that enabled the Xenobot to perform what the researchers call motion-based "kinematic replication."

This phenomenon has been observed on the molecular level, where molecules will replicate by moving toward and combining with other building blocks to form copies of themselves. This has never been seen before in whole cells or organisms, but the design spat out by supercomputer resulted in a Xenobot capable of doing just that.

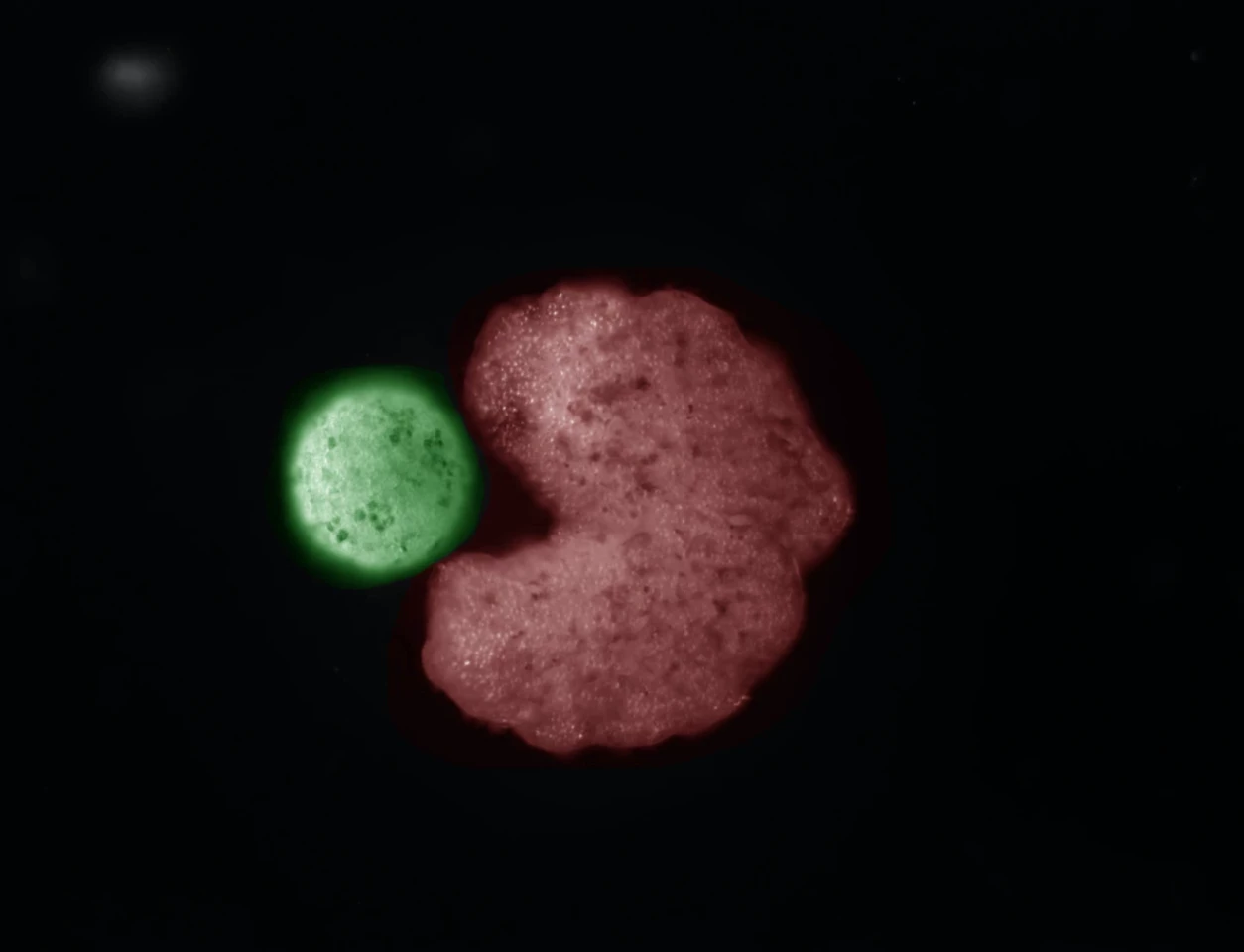

“We asked the supercomputer at UVM to figure out how to adjust the shape of the initial parents, and the AI came up with some strange designs after months of chugging away, including one that resembled Pac-Man,” says Kriegman. “It’s very non-intuitive. It looks very simple, but it’s not something a human engineer would come up with. Why one tiny mouth? Why not five? We sent the results to Doug (co-author Douglas Blackiston) and he built these Pac-Man-shaped parent Xenobots. Then those parents built children, who built grandchildren, who built great-grandchildren, who built great-great-grandchildren.”

These Pac-Man-shaped Xenobots swim around the dish gathering hundreds of single cells and assemble babies inside their mouths that develop into Xenobots that look and move just like their parent robot within a few days. These new Xenobots can then do the same, building copies of themselves over and over again.

“This is profound,” says study author Michael Levin. “These cells have the genome of a frog, but, freed from becoming tadpoles, they use their collective intelligence, a plasticity, to do something astounding.”

The scientists note that no animal or plant is known to reproduce in this way, and consider the new generation of Xenobots the ideal vehicle to study self-replicating systems. While the idea of self-replicating robots may be cause for concern among some, the team notes the controlled environment in which its experiments are taking place and the ease with which they can be extinguished.

The hope is that these types of replicating robots can help humanity more rapidly solve complex problems. This could mean developing machines to clean microplastics from waterways, developing vaccines for novel viruses or medicines for all manner of ailments.

“If we knew how to tell collections of cells to do what we wanted them to do, ultimately, that’s regenerative medicine – that’s the solution to traumatic injury, birth defects, cancer, and aging,” says Levin. “All of these different problems are here because we don’t know how to predict and control what groups of cells are going to build. Xenobots are a new platform for teaching us.”

The research was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Source: Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University