The popular pain-killing drug paracetamol, also known as acetaminophen, has always been made from chemicals derived from environmentally damaging coal tar or crude oil. Now researchers have devised a greener way of producing the drug using wood from the poplar tree.

First synthesized in the 1800s, paracetamol, known in the US and Japan as acetaminophen, is one of the most commonly used over-the-counter drugs for pain and fever in the world. Sold as Tylenol and Panadol, it even appears on the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines.

The (bad) thing about paracetamol is that, like most pharmaceuticals, it comes from non-renewable petrochemicals. In fact, it used to be known as a ‘coal tar analgesic’ because the starting material for the commercial manufacture of paracetamol is phenol, derived from the distillation of coal tar, which possesses analgesic properties. These days, industrial phenol is usually synthesized from crude oil rather than coal tar, which still presents environmental issues.

Given the planet’s limited fossil fuel supply and the global challenge of achieving net zero emissions, researchers from the University of Wisconsin–Madison have devised a greener way of producing paracetamol: trees.

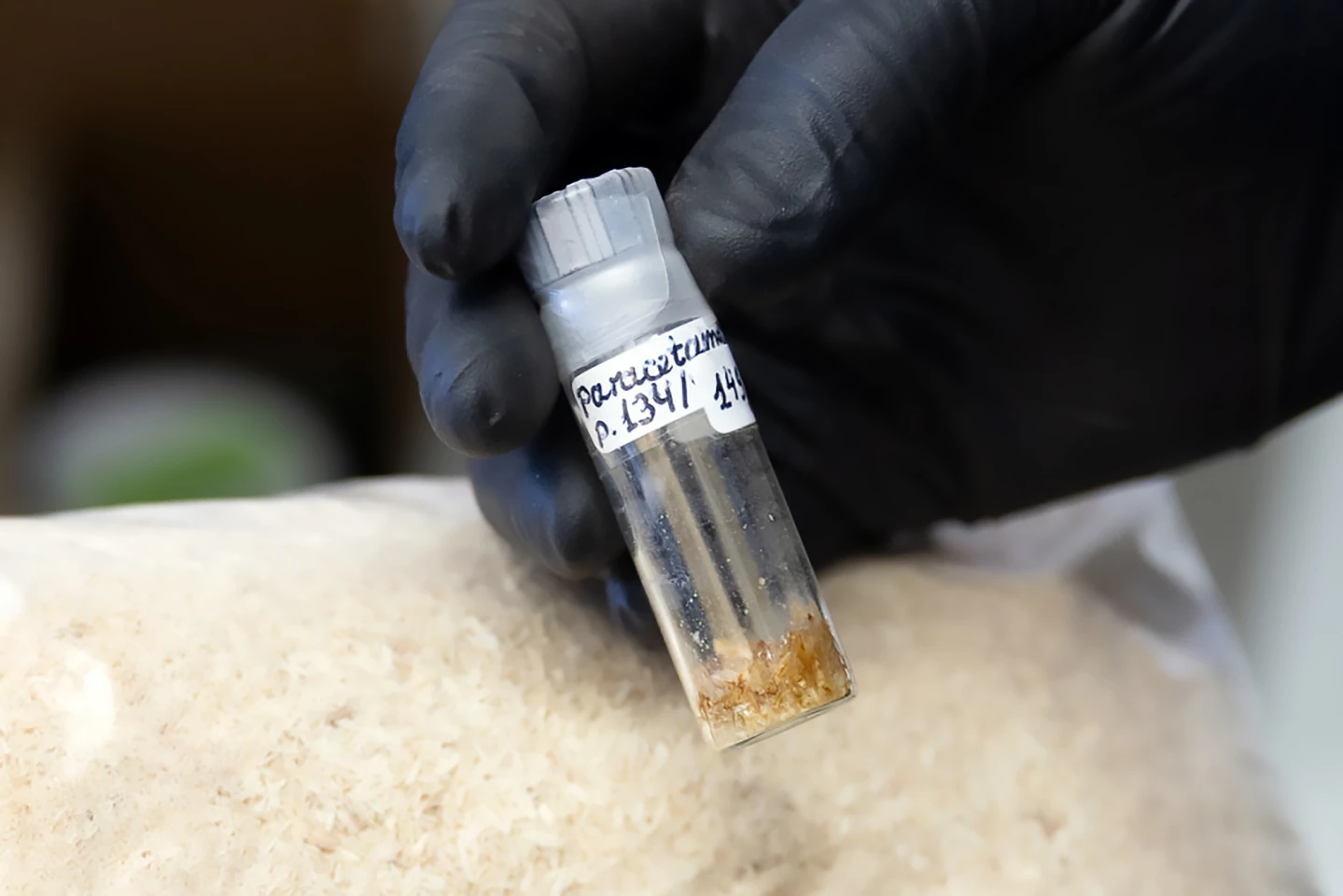

In 2019, a team led by John Ralph, a professor of biochemistry at UW–Madison, and Steven Karlen, a staff scientist at the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center, was awarded a patent for their method of synthesizing paracetamol from lignin, a class of complex organic polymer that acts as a ‘backbone’ to certain plants. Since then, they’ve continued refining the process.

First, some chemistry. The paracetamol molecule (N-acetoxy-p-aminophenol) consists of a six-carbon benzene ring with two chemical groups – a hydroxyl group and an amide group – attached. The lignin found in poplar trees produces a similar compound, p-hydroxybenzoate (pHB). However, given its complex and irregular molecular structure, lignin is challenging to break down into useful components.

Rising to the challenge, the researchers developed a way of breaking down pHB into another chemical and then converting it to paracetamol (or other products that have other applications).

“You can make dyes like black ink, polymers which can be used in textiles or material application, convert it to adhesives or into stuff like that,” said Karlen. “It’s got a huge market and big value.”

There is more chemistry here; feel free to skip it if it doesn’t interest you. The method has three processing stages. In the first, the plant-based pHB is broken down to p-hydroxybenzamide (pHBA). In the second stage, a continuous reaction process converts pHBA to p-aminophenol and recovers the unreacted pHBA. (In a continuous reaction, all chemical operations occur together, and the processed material is not divided into separate portions like in a batch reaction.) The third stage involves acetylating p-aminophenol to paracetamol.

The researchers found that this process produced a pHBA-to-paracetamol yield of around 90%, with a paracetamol purity of greater than 95%. Karlen says it should be possible to boost the yield to 99% with further work.

Compared to traditional approaches, the new method has several benefits. It’s cheaper, primarily water-based, relies on green solvents, and is continuous rather than a batch reaction, making it ideal for industrial applications.

“We did the R&D [research and development] to scale it and make it realizable,” Karlen said. “As I’m chopping the tree up, it can feed right into a reactor that pulls out the benzamide. So you’re never stopping. As fast as your trucks can come in and fill that hopper, you can keep processing.”

In 2022, the global market for pHBA was around 42,500 tons and valued at US$66 to 85 million. The researchers calculate that it would take 10 biorefineries processing 1,000 tons/day of poplar wood with a pHBA level of 1.2 wt% to meet that demand. They suggest that constructing a network of smaller biorefineries to feed larger hub refineries to upconvert the products would be a viable option and would expand the scale of the product market from around $85 million to $1.5 billion. And, they say, the other valuable products that can be produced by the process have the potential to also add value.

The study was published in the journal ChemSusChem.

Source: UW–Madison