New research has found that reducing the intake of a single amino acid, isoleucine, by two-thirds, improved the lifespan, weight, and health of middle-aged mice without requiring a drop in calorie intake. The findings suggest that limiting dietary levels of isoleucine may be a key to healthy aging.

What you eat has a strong influence on health and longevity. However, adhering to a calorie-restricted diet can be difficult, generating interest in developing interventions that mimic a calorie-restricted diet without reducing calorie intake.

Studies into the benefits of protein-restricted diets have shown that lower protein consumption is associated with a decreased risk of age-related diseases and mortality and improved metabolic health. Now, exploring alternatives to calorie-restricting diets, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have found that reducing the intake of a single amino acid in mice extended their lifespan, making them leaner, less frail, and less susceptible to cancer.

“We like to say a calorie is not just a calorie,” said Dudley Lamming, corresponding author of the study. “Different components of your diet have value and impact beyond their function as a calorie, and we’ve been digging in on one component that many people may be eating too much of.”

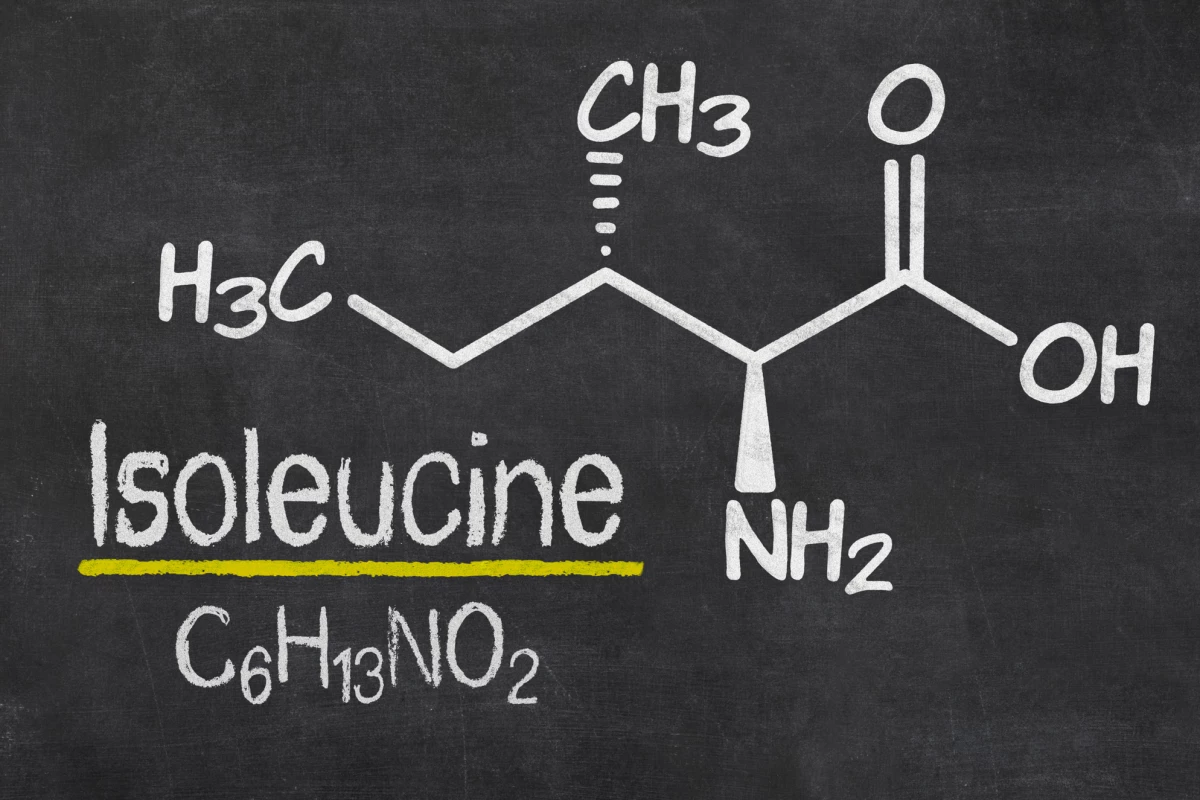

That one component is isoleucine, one of nine essential amino acids. Data from an earlier study into the health of Wisconsinites found that those with a higher BMI tended to consume more isoleucine, which is plentiful in foods including eggs, dairy, soy protein and many meats.

To further investigate the effects of isoleucine on health, the researchers placed male and female genetically diverse mice on one of three amino-acid-defined diets. The control diet contained all 20 common amino acids, reflecting a natural chow where 21% of calories are derived from protein. The other diets either reduced all amino acids or reduced isoleucine only by 67%. All three diets had identical fat levels; that is, they were isocaloric.

The mice were around six months old at the start of the study, roughly equivalent to a human in their 30s, and could eat as much as they wanted.

“Very quickly, we saw the mice on the reduced isoleucine diet lose adiposity – their bodies got learner, they lost fat,” Lamming said. In comparison, the mice eating the low-amino-acid diet initially got leaner but regained weight and fat.

The researchers found that mice on the reduced-isoleucine diet lived longer compared to controls; males, on average, 33% longer and females 7%. In addition to lifespan improvements, there were improvements in ‘healthspan’. In reduced-isoleucine-fed males, there was a strong negative correlation between lifespan and frailty measures associated with body condition, including tail stiffness, fur color, and tremor occurrence. In control-fed females, lifespan strongly positively correlated with whisker loss, hair loss, and spinal curvature (kyphosis), whereas in reduced-isoleucine-fed females, these deficits correlated negatively with lifespan.

Notably, a diet where all amino acids were reduced, including isoleucine, was found to improve aspects of healthspan in both sexes and slowed frailty to the same extent as the low-isoleucine diet but did not extend lifespan in either male or female mice.

“Previous research has shown lifespan increase with low-calorie and low-protein or low-amino-acid diets starting in very young mice,” said Lamming. “We started with mice that were already getting older. It’s interesting and encouraging to think a dietary change could still make such a big difference in lifespan and what we call ‘healthspan’, even when it started closer to mid-life.”

The reduced-isoleucine-fed mice ate significantly more calories than their counterparts, which, the researchers say, was probably due to them trying to increase their isoleucine intake. But they also burned more calories, losing and maintaining leaner body weights simply through adjustments in metabolism, not by getting more exercise.

The mice also maintained better blood sugar control, and male mice experienced less age-related prostate enlargement. And while cancer is the leading cause of death for the genetically diverse mice used in the study, the low-isoleucine-fed males were less likely to develop a tumor.

The mechanisms of the health benefits provided by a reduced isoleucine intake are poorly understood and will require further research. Additional research will also be needed to determine whether there are negative effects of isoleucine restriction and to examine how optimal levels of the amino acid vary with age and sex.

“That we see less benefit for female mice than male mice is something we may be able to use to get to that mechanism,” Lamming said.

The researchers note some of the study’s limitations. They examined only a single level of restriction, and other studies into calorie- and protein-restricted diets suggest that different mouse strains and sexes may respond optimally to different restriction levels. Also, to keep the diets isocaloric, the reduction of amino acids in the low-amino-acid diet was balanced by additional carbohydrates, and the reduction of isoleucine was balanced with non-essential amino acids.

Complicating matters is that humans need isoleucine to live. It’s the oxygen-carrying pigment inside red blood cells and helps make hemoglobin, and is required for important functions like muscle protein synthesis, energy production and immune system support.

“We can’t just switch everyone to a low-isoleucine diet,” Lamming said. “But narrowing these benefits down to a single amino acid gets us closer to understanding the biological processes and maybe potential interventions for humans, like an isoleucine-blocking drug.”

The study was published in the journal Cell Metabolism.

Source: University of Wisconsin-Madison